Will new penalty system give Hong Kong’s notorious taxi trade a fresh start?

Passengers and cabbies alike remain sceptical that stiffer fines and demerit point system will resolve industry’s entrenched issues

The cabby, frowning, asked twice if she really wanted to cross Victoria Harbour to go to Hong Kong Island. She said yes without hesitating, and he began driving.

At Ho Man Tin, about two-thirds into her journey, the driver suddenly pulled over at Princess Margaret Road and told Wong to get out, saying there was bad traffic congestion ahead.

“This is bizarre and outrageous,” Wong, in her 40s, said. “I did not even complain about the cigarette smell in the taxi or the broken seat.”

Her experience is neither unusual nor the worst of a host of complaints that prompted the Transport Department to propose stiffer fines and penalties for errant taxi drivers.

But both cabbies and riders are unconvinced the measures go far enough to fix the industry’s entrenched problems.

Ban on taxi drivers after first offence too much, transport chief says

“This is a knee-jerk reaction to long-standing problems,” said Hung Wing-tat, a transport policy expert at Hong Kong Polytechnic University and chairman of the Hong Kong Taxi Council. “The government has yet to show its desire and effort to reform the industry.”

In the city, 18,163 taxis serve almost a million customers daily, and while there were 220,440 people with taxi driving licences as of September 2016, only about 40,000 were actually using them.

A stick without a carrot

For years, Hong Kong cabbies have been notorious for everything from refusing to pick up fares and cherry-picking their destinations to overcharging passengers and making unnecessary detours.

There are ill-maintained vehicles and worries about road safety with almost one in every five traffic accidents involving a taxi.

Taxi services, or the lack of, accounted for nearly half of all gripes to the government’s Transport Complaints Unit from 2013 to last year. During that same period, police initiated about 1,200 prosecutions annually for taxi-related offences.

Cabbies face stiffer fines, more jail time in bad service crackdown

Last month the Transport Department rolled out a raft of proposals including slapping 10 demerit points on cabbies for six offences – refusing to go to the rider’s destination, refusing to pick up a passenger, overcharging, not taking the most direct route; tampering with the meter and soliciting. Five other offences bring five demerit points each.

A cabby who chalks up 15 demerit points will be suspended for three months. A repeat offender could be suspended for six months.

Existing maximum penalties of a HK$10,000 (US$1,280) fine and a six-month jail term for serious offences will remain for first offenders, and a maximum fine of HK$25,000 and a 12-month sentence for repeat offenders will be introduced.

Making drivers dress properly an outdated concept, taxi boss says

The department aims to implement the changes from next year.

Unimpressed, cabby Franco Cheung, 31, said: “The demerit point system is good, but I have concerns about details and enforcement, and there is a lack of clarity that may end up causing more disputes between drivers and passengers. It is a stick-without-a-carrot system, which does not motivate those who behave.”

Cheung, a Shue Yan University graduate who became a cabby two years ago, is among the minority of taxi licence holders aged below 50.

Acknowledging there were unscrupulous drivers and problems to fix, he recalled how he was once at the popular Lan Kwai Fong nightspot area when a Westerner jumped out of the taxi in front of him and got into his vehicle instead. The passenger said the other cabby had demanded HK$400 for a ride to North Point, when the usual fare was only HK$50.

“Lan Kwai Fong is a black spot for locals and tourists,” Cheung said.

He is not the only one with reservations.

Unethical drivers and unfair passengers

Wong Po-keung, chairman of the 1,000-strong Hong Kong Taxi Owners’ Association, said many drivers were worried about the prospect of passengers setting them up by lodging unfair complaints.

“We need more details about the rules and enforcement – there are many situations which will put drivers at higher risk,” said the 71-year-old Wong, who still drives his taxi.

He recalled the case of cabby Tam Hoi-chi who was taken to court in 2013 after a passenger complained he rounded up her HK$136.50 fare and did not return 50 cents.

Wong accompanied the cabby to court during the case, which dragged on for six months before Tam was cleared of wrongdoing.

“Rounding to the nearest dollar is common practice, and there are some passengers who are not necessarily fair to us,” Wong said. “Tam was in great distress and had to forgo six months of earning a living.”

Wong said some drivers were angry and threatened to protest against the new penalties, but he did not think demonstrations would resolve their unhappiness.

Taxi driver cleared of keeping 50 cents’ change

He urged the government to clear up some ambiguities about how the new system would be enforced, citing disputes that might arise between cabbies and passengers. For example, what happens when a driver who is nearly ending his shift at 4pm declines a fare but gets reported for refusing to pick up a passenger? That is one of the six serious offences carrying 10 demerit points.

Drivers could be reported for not taking the most direct route, but Wong pointed out the shorter way could be badly congested whereas a longer trip without traffic jams would be faster.

“In this situation, what should the driver do to avoid being caught?” he asked.

The Transport Department has encouraged drivers to install in-cab cameras to record interactions with their passengers and help settle disputes, but Wong said that could lead to further complications involving issues such as privacy and personal data protection.

“It is not feasible if the government does not intervene by taking charge of storing and managing all the camera footage,” Wong said.

The need for competition

Critics doubted whether the penalties were sufficient to address the causes of notorious problems in the taxi trade.

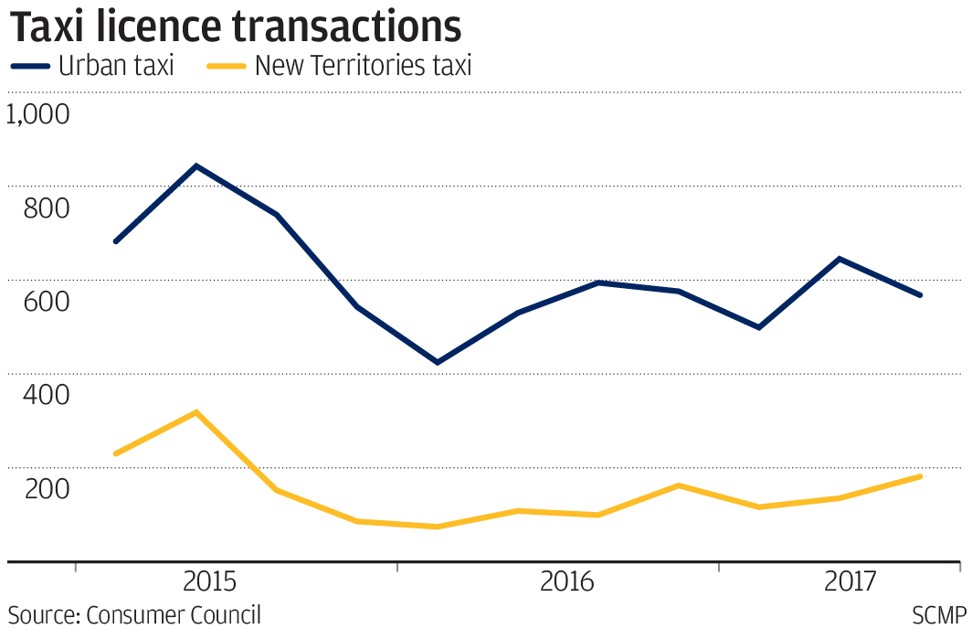

Key among these is the way licences to buy taxis are traded in Hong Kong. The Transport Department stopped issuing new licences in 1994, with a total of 18,163 issued which the authorities decided was enough.

A Transport Department review last year found the taxi supply was sufficient to meet demand.

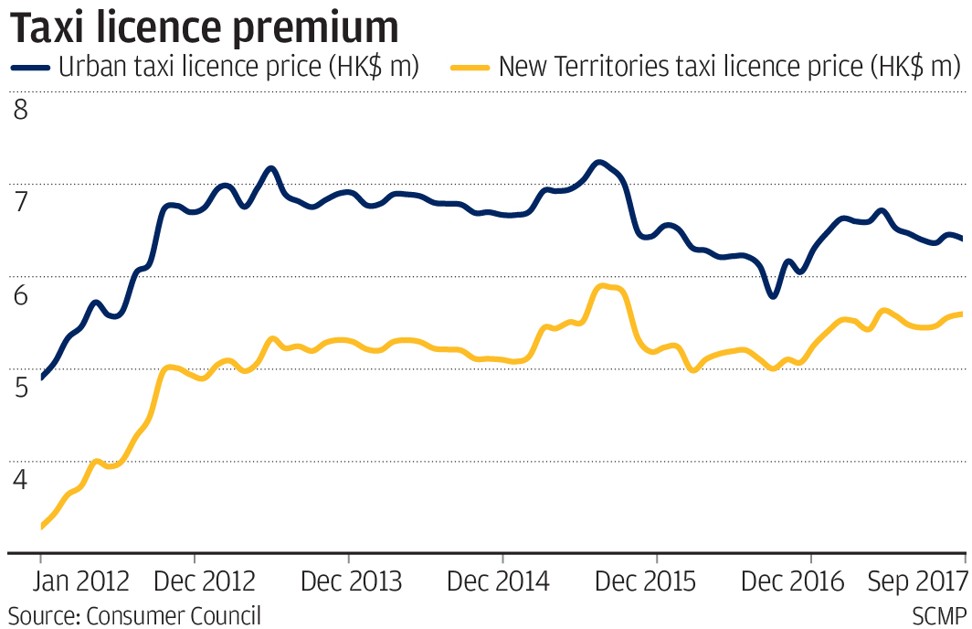

The licences are permanent, and holders may sell them. They now change hands for millions of dollars, with urban taxi licences for red cabs, for example, fetching between HK$5.5 million and HK$6 million at present.

As the government has no power to revoke these taxi licences, or add any conditions, it is up to the licence holders to decide quality of the service they provide.

A government report in 2017 said about 60 per cent of the 18,163 licences are held by individuals and the rest by companies. One licence covers one taxi.

Why Hong Kong cabbies are reluctant to ditch cash

Based on a licence-trading platform online, urban taxi licences – for red taxis – are worth anywhere between HK$5.5 million and HK$6 million at present, with a historical high of more than HK$7 million in 2015 and a low of about HK$3.5 million in 2007.

Democratic Party leader Wu Chi-wai said Hong Kong needed more competition in the taxi industry and urged the government to relax its rules to allow ride-hailing services such as Uber, which are currently illegal although the government has done little to crack down on them.

Despite facing prosecution and fines, such services continue to operate in the city.

Cabbies eager to guard their turf are dead against ride-hailing firms, but Wu, an Uber supporter, said market forces should be allowed to determine the quality of service.

“At the heart of the issue lie two vested interest groups – taxi owners and drivers,” Wu said. “But the government has bowed down to taxi owners’ interests.”

Taxis in Hong Kong will speed up reform if ride-hailing firms can compete legally

In a recent submission to the government, pro-democracy Professional Commons vice-chairman and IT sector lawmaker Charles Mok called for a revamp of the industry by rejuvenating the mechanism for issuing taxi licences, allowing flexible fares and lowering the entry barrier to the application for hire car permits to bring in more competition.

In written replies to questions from the Post, a Transport Department spokesman said it had been “striving to enhance the service quality and operating environment of the existing taxis in a holistic manner” and to “facilitate long-term healthy development of the taxi trade”.

He pointed out the authority had been educating drivers through training courses and encouraging them to use technology to improve services.

The department promised to communicate with the taxi trade and related stakeholders and to “adopt an open attitude in listening to their views” for feasible measures to improve services.

Future of franchised taxis

The Transport Department floated a plan last year to launch franchised taxis as a premium service, but taxi owners were dismissive, saying it would go nowhere in improving service. A bill on franchised services is expected to be tabled to the Legislative Council in the 2018-19 legislative year.

Meanwhile, Wong of the Taxi Owners’ Association highlighted the urgent need to find younger drivers. With four in five drivers with taxi licences aged 50 and above, he wanted the government to lower the minimum age for cabbies from of 21 to 20.

Wong, who started driving a taxi 50 years ago when he turned 21, said he wanted to retire six years ago but could not find younger drivers to take over.

He has three taxis and about six drivers working for him, the youngest in his 50s and the oldest, 82.

“I can never retire,” he said.

Wong added that if cabbies worked two shifts a day, for 12 hours each, they could earn about HK$1,200. Taking into account fuel cost and rent, the daily net income would amount to about HK$700 – a total of HK$16,800 a month for working six days a week.

What micro flats and crackdown on Uber tell us about Hong Kong’s economy

“This is even lower than a bus driver’s monthly take home pay,” he said.

Cabbies like Cheung, who do not own their vehicles, feel the owners themselves are part of the problem – they trade their licences as an investment, drive up licence prices and give few incentives to motivate hirers to improve service standards.

“Taxi drivers like me who do not own a taxi are discouraged by the black sheep, who still earn more than we do even after they get fined for offences,” he said.