Hong Kong protests: can new police chief’s strategy to act fast, get tough and cripple the movement?

- Hong Kong is marking a year since the anti-government movement began

- The new police chief’s strategy has impacted the unrest amid growing international interest and during US police strife

As Hong Kong marks a year since anti-government movement began, this article is second in a series analysing how key players have fared.

Anti-government protests that began last June showed no sign of ending, with clashes between masked radicals and frontline officers becoming increasingly violent.

Hong Kong’s 31,000-strong police force was under fire, its public approval ratings at rock bottom, morale was shaken and some officers even chose to quit.

03:06

New Hong Kong’s police chief on duty after China appointment amid ongoing protests

Security consultant Clement Lai Ka-chi, a former police superintendent, said recent riots across the United States have provided an insight into perceptions of police brutality. Lai noted that Hong Kong police had been relatively restrained in dealing with protesters even after violence occurred.

But at the time, the unrest in the US had not started and there were no grounds of comparison.

“Enough is enough,” he said, urging people to condemn, not glorify violence. “We can only end the unrest with society’s condemnation, reflection by the rioters, plus our appropriate tactics.”

Tang could not force Hongkongers to do as he hoped, but he proceeded to change the way police dealt with protesters and violence. Half a year into his tenure, its tactics have become noticeably different.

Insiders say he is behind the switch from the previous “passive, defensive” response to a “proactive and determined” approach to protesters. Tang’s way was on display on January 1, when the first major rally occurred on his watch.

06:16

Hong Kong New Year’s Day march cut short, descends into chaos

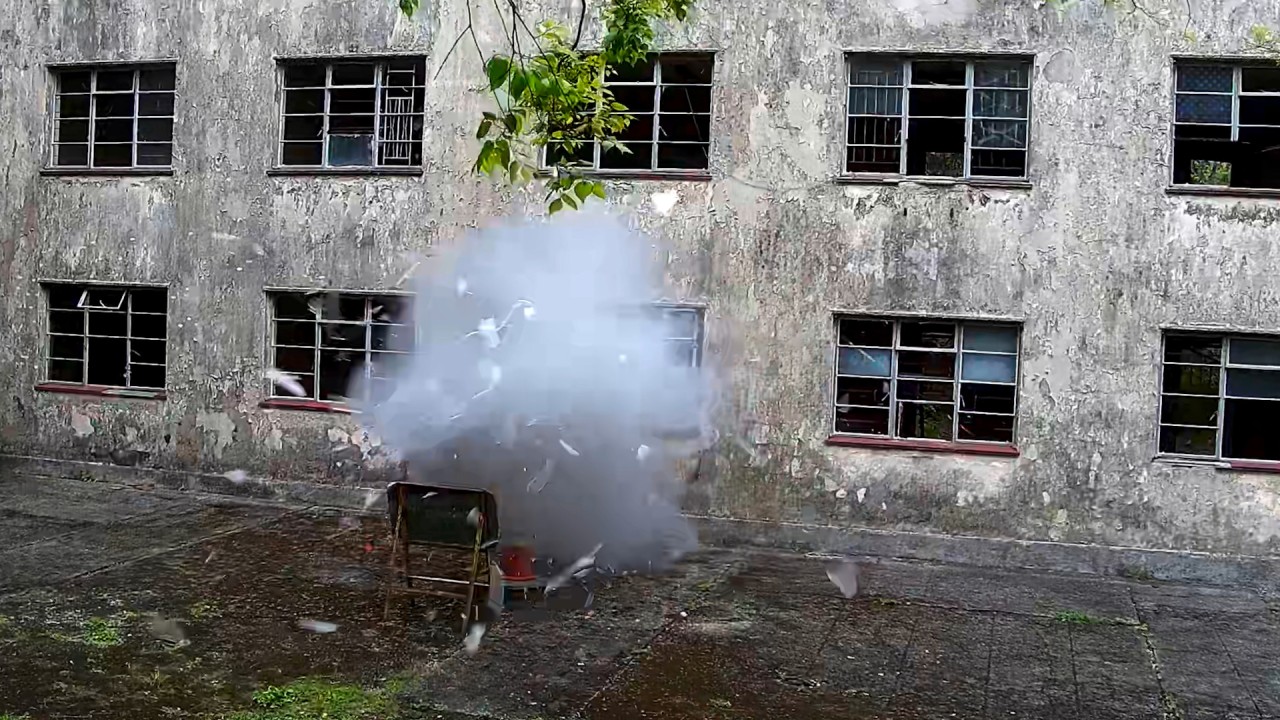

In scenes that had played out numerous times through the second half of 2019, a peaceful march plunged into chaos as masked radicals tore through Causeway Bay, Wan Chai and Central, blocking roads, throwing petrol bombs, trashing bank branches and shops, and even defacing the High Court with graffiti.

Unlike before, however, police swung into action swiftly, dispersing the crowds and rounding up 460 people near the Sogo department store in Causeway Bay.

A senior officer said: “We used to play a drawn-out defensive game when dealing with radical protesters. We even let protesters continue marching in illegal rallies, dispersing them only when massive violence erupted. Now, once violence occurs, we intervene early.”

Quicker action also meant using fewer rounds of tear gas and other crowd-dispersal weapons, he added.

Police increased security around the legislature, erected additional barriers, sent riot officers to patrol the area and set up checkpoints to screen those entering the Legco complex. Several tow trucks were on standby along major roads to remove any vehicles deployed to disrupt traffic.

Among those arrested that day were five teenagers suspected of possessing petrol bombs, goggles, helmets and a screwdriver. They were caught in Sham Shui Po, Tsuen Wan and Kwai Chung.

“Overall, our early intervention and resolute enforcement actions proved to be effective,” Tang told his men that evening over the police radio.

What are the weapons police can use, and how dangerous are they?

Fear of ‘budding local terrorism’

Last month, Tang expressed support for Beijing’s move to draw up a national security law for Hong Kong, saying the explosives seized were commonly used in terrorist attacks overseas.

He warned that Hong Kong was at risk, and effective measures were needed to prevent the situation from deteriorating.

The city’s top police operations commander, Raymond Siu Chak-yee, told Legco last week that in 18 cases involving explosives and firearms over the past year, police arrested 76 people and identified at least seven “radical local groups”.

In raids on 22 locations in March, officers arrested 17 people and seized weapons and explosives, including 2kg of the powerful explosive TATP and an AR-15 rifle.

01:29

Hong Kong police say they are dealing with “almost unprecedented” number of bomb attempts

He said Hong Kong already had the laws to deal with terrorism, based on Britain’s anti-terrorism legislation. Quizzed last week by lawmakers who argued that the UN had recommended not to include damage of properties into terrorism laws, Lee said: “If there is serious damage to property, we think that is one of the [definitions] of a terrorist act.”

Simon Young Ngai-man, associate law dean at the University of Hong Kong and a specialist in anti-terrorism law, said the terrorism label would give the government wider powers to freeze and forfeit the property of suspects.

It would also make it easier to prove criminal offences by other parties linked to those suspects, including those who supply them with funds or financial services.

“Ordinary businesses will need to be much more vigilant about who they are dealing with,” Young said.

Morale, image and pressing on

Between June 2019 and May 2020, police arrested 8,981 people in relation to the protests, fired 16,223 rounds of tear gas, 10,108 rubber bullets, 1,885 sponge grenades, 2,033 beanbag rounds and 19 live bullets.

The widespread use of social media through the months of protests meant there was live coverage of events, as well and mass circulation of particular incidents.

Images and video clips of police officers confronting, chasing, arresting or pinning down protesters were shared widely. In one incident, officers were seen beating four cowering protesters on a train at Prince Edward station.

03:07

Chaos on Hong Kong’s rail network as police chase protesters into station, beat people on train, arrest over 60

There were also allegations that police had mistreated or assaulted those who were detained, with some accusations of sexual abuse.

Police chief tried to discredit me, says girl who accused officers of gang rape

Protesters, human rights activists and opposition lawmakers have accuse police repeatedly of brutality.

Political and corporate risk consultant Steve Vickers, a former senior police officer, said while the force might not have been blameless, the extent of their actions was exaggerated when footage from incidents was shared widely and repeatedly. False allegations against police were also common online, he added.

By November 2019, the public satisfaction rating for police sank to a record low of 27.2 per cent, according to the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute.

03:05

HK protests: Watchdog says police use of force met international guidelines but has room to improve

As mutual hostility deepened, name-calling became common, with some officers referring to protesters as “cockroaches,” while the protesters called police “dogs”. As of February, there were 1,641 complaints made against officers related to the protests.

Police chief apologises to reporters mistreated by officers at Mong Kok protest

Unknown to the public, morale among lower police ranks slid drastically and at one point, some officers contemplated a strike, according to Lam Chi-wai, chairman of the Junior Police Officers’ Association which represents 80 per cent of the force.

He said the period from June to October 2019 proved most difficult, as many officers were not psychologically prepared for the protest movement’s smear campaign. “Their propaganda attack was unparalleled. To be honest, we were overwhelmed,” Lam said.

Between November 2019 and May 28 this year, police wrote 81 letters to the media objecting to fake or biased reports, compared to just six such letters between June and November last year.

No fewer than 62 letters were sent to Chinese-language Apple Daily, which regularly featured front-page splashes of alleged police brutality.

Tang also made an official complaint to the Communications Authority against public broadcaster RTHK over two episodes of its long-running satirical show, Headliner, claiming that they “undermined police work” and would result in an “erosion of law and order”.

It made 52 recommendations, including a review of the force’s operational command structure, more training for officers, clear guidelines on the use of weapons, and a task force to advise on the frequent use of tear gas.

Human rights advocates and opposition lawmakers attacked the credibility of the IPCC report. They have continued to hit out at police handling of protests, including the new strategies in place since Tang took the helm.

Concerned about swift, mass arrests at protest sites, Icarus Wong Ho-yin, convenor of Civil Rights Observer, said genuine passers-by could end up being detained.

“Police are using their power wrongly to send a chilling effect to those who want to attend assemblies,” he said.

Concerned about the government’s threat to declare some protest-related incidents acts of terrorism, he said other laws should be used to deal with crimes such as participating in an unlawful assembly or rioting.

While you may well be operating within the legal framework, the question is whether people think you acted reasonably

Assistant Professor Lawrence Ho Ka-ki, of the department of social sciences at Education University, who specialises in the history and sociology of policing, acknowledged that police faced new challenges given the way protests are live-streamed.

“A lot of things done by police can be justified in legal terms, because Hong Kong law grants huge power to the executive branch and law enforcers,” he said. “But while you may well be operating within the legal framework, the question is whether people think you acted reasonably.”

There is no police force in the world that would tolerate the violence used by the rioters in Hong Kong

Deputy Commissioner of Police Raymond Siu Chak-yee said police had the duty to maintain law and order and ensure public safety, especially when people committed crimes and caused serious disturbances.

He pointed out that in the early stages of the social unrest, protesters threw plastic bottles, metal rods and bricks at officers. Later, police were attacked with lethal weapons such as bows and arrows, petrol bombs, explosives and firearms.

He said he was stunned by the level of violence, and how organised the protesters appeared to be in carrying out their actions.

03:04

Petrol bombs and water cannons as Hong Kong descends into violence once again

“Violence invites a forceful response, and that applies to police forces all over the world,” Siu told the Post. “When violence occurs, we need to use an appropriate level of force to restore public order and bring offenders to justice. There is no police force in the world that would tolerate the violence used by the rioters in Hong Kong.”

As for ongoing accusations of police brutality and human rights violations, he said: “They talk about human rights, but they brutally assault innocent members of the public. Do you call this human rights? When somebody holds different views from them, they attack and vandalise shops. Do you call this freedom of expression?”

Security consultant Clement Lai said: “We can see on TV that US police officers pin down protesters just for shouting at them.”

Police chief says bumper budget increase is vital in fight against ‘new normal’

But Lai cautioned against making direct comparisons, saying US police officers faced a higher level of violence at work, and Americans were also allowed to carry arms.

In a major boost to the Hong Kong police in May, Legco approved a 7 per cent increase in manpower for the new financial year, creating 2,543 additional posts. The total operating expenses for the force this financial year rose by a whopping 24.7 per cent to HK$21.9 billion (US$2.8 billion).

According to the Security Bureau, between last June and February this year, nearly 450 police officers quit the force before they were due to leave.

08:47

A year of anti-government protests in Hong Kong

The number of new hires also fell short of targets between April 2019 and February 2020 and police rehired 1,110 officers who had retired or were due to retire.

But Deputy Commissioner Oscar Kwok Yam-shu, who is in charge of hiring, was confident the force would still attract the best into its ranks.

Although it hired only 766 officers between April 2019 and February this year, it received 10,846 applications.

“This is an important job that they would like to get into,” he said. “I really commend these young men and women for having the courage and commitment to take up this mission.”

The first article in the series discusses the future of a movement beaten into retreat by a pandemic and looming national security law.