Hong Kong protests: Civil Human Rights Front refuses to cooperate with police investigation into its activities

- Group convenor says ‘on principle’ it will not answer questions from police about its finances, operations and legal basis, which lawyers say could heighten ban risk

- Front’s future is uncertain amid a police investigation; force is awaiting official response before weighing next step

A prominent Hong Kong opposition group best known for organising mass protests told police on Tuesday it would not cooperate with a force investigation into its legality and activities, a stance lawyers said could make an outright ban more likely.

The future of the Civil Human Rights Front has been hanging in the balance since police informed the organisation last Monday it was subject to a probe into its finances and the failure to register with the government under the Societies Ordinance.

Police have given the front until Wednesday to provide information on its funding, expenses and related bank accounts.

Hong Kong’s biggest opposition party latest to leave Civil Human Rights Front

The force has also demanded an explanation for the organisation’s participation in a joint declaration to the United Nations last December, a move which pro-establishment figures said might have violated the national security law.

Formed in 2002, the front was the driving force behind the following year’s July 1 march which drew hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers to protest against a national security bill that was later shelved. It was also behind several massive anti-government demonstrations in 2019.

Breaking the group’s silence on the investigation, its convenor said police had been communicating with members for many years without raising any issues.

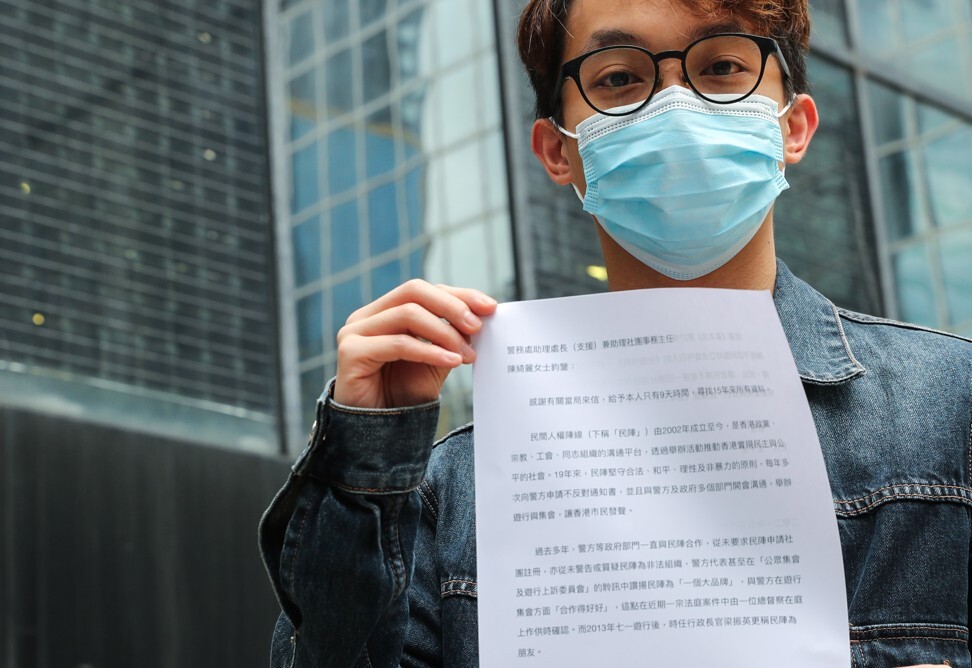

“Following the July 1 march in 2013, then chief executive Leung Chun-ying even referred to the Civil Human Rights Fronts as ‘friends’,” Figo Chan Ho-wun said.

Chan further asserted the group was a lawful entity because the city’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, guaranteed the freedom of assembly.

He added the organisation also disagreed with the basis of the Societies Ordinance, under which police had the power to investigate the group – and possibly ban them.

“As such, please accept that the Civil Human Rights Front will not respond to every single question raised by the societies officer,” he said, directing his remarks to the deputy police commissioner assigned the role, who had filed several queries to the group.

Chan said the front was given only nine days to respond to police’s six questions asking them to provide details – such as information relating to its finances and event logs – spanning a 15-year period.

He said a company would usually only keep financial records for up to eight years for tax purposes.

But he said the group did not intend to hand those details to police even if they still held them. “It’s a matter of principle,” the activist said.

Under the Societies Ordinance, an office bearer could be fined up to HK$20,000 for refusing to provide information as requested, or for handing over false information.

Two lawyers speaking on condition of anonymity said the group faced a higher chance of being banned by refusing to comply with police’s requests.

But barrister Billy Li On-yin said keeping silent might not make a difference to the front’s plight because it was simply opting not to advance arguments that might support or undermine its case.

A police source said they would have to study the group’s official response and seek legal advice from the Department of Justice before deciding the next move.

A police spokesman said it would handle cases based on the actual situation and in accordance with the Societies Ordinance.

The police probe came a month after Lianhe Zaobao, the largest Chinese-language daily newspaper in Singapore, reported the Hong Kong government was seeking to ban the group on national security grounds.

The law states the police societies officer may recommend the city’s security minister ban a society or its branch if found to be a political body connected to a political organisation overseas or in Taiwan.

Prohibition could be deemed necessary in the interests of national security or public safety, as well as to uphold public order or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

07:30

China’s Rebel City: The Hong Kong Protests

Chan was speaking outside the District Court on Tuesday, where he was facing one count of inciting others to take part in an unauthorised assembly in June 2019, a charge punishable by three years in prison.

Asked to speculate on what would happen if the group was banned, Chan said he believed other civil groups would pick up the mantle.

“But I may be the last convenor of the Civil Human Rights Front,” he said.

In 2018, the government outlawed the Hong Kong National Party on national security grounds under the Societies Ordinance. The party advocated for Hong Kong independence.

Additional reporting by Christy Leung