Will Hong Kong ever hit its public housing target? Carrie Lam says yes, but city data suggests otherwise

● Top official vows to increase proportion from stated 60 per cent goal

● Analysts question target and point to recent record of building delays

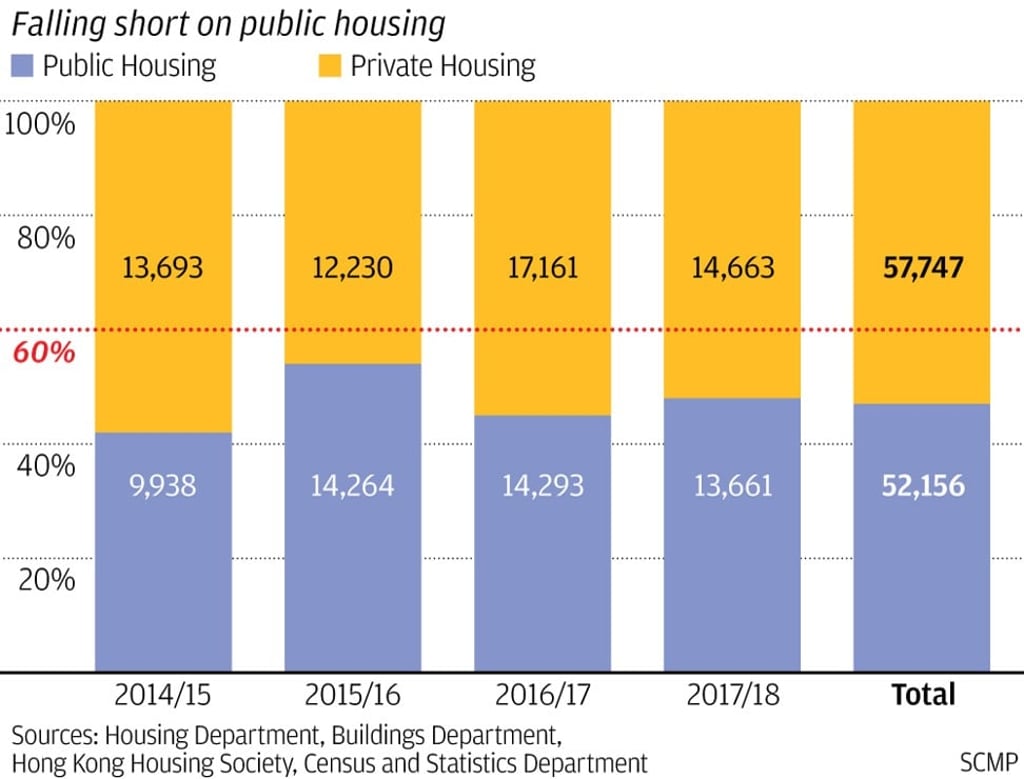

The Hong Kong government has never hit its target of building enough public flats to account for 60 per cent of the total housing supply, official statistics showed, even as the city’s leader vowed to reach a still more ambitious goal.

Under the government’s long-term housing strategy, officials set a target of building 460,000 units by 2027/28. From this total, 60 per cent, or 280,000, would be public rental housing and subsidised flats, while the remaining 40 per cent, or 180,000, would be private flats.

However, data compiled by the Post showed the government failing to achieve the target of a 60:40 split every year since the strategy was adopted in 2014.

Across Hong Kong, 109,903 flats were built between April 2014 and March this year. Public housing flats only accounted for 47 per cent of the figure, while private flats comprised 53 per cent.

The latest statistics showed 28,324 flats were built in total between April 2017 and March 2018. Public housing flats only made up 48 per cent, with private flats accounting for other 52 per cent.