Hong Kong youth addicted to internet need to be understood instead of judged, experts say

- Children who spend too much time online may not all be addicts, but need help navigating digital world

- As parents and children clash, experts call for more cross-discipline research to work out solutions

Hongkonger June* was just eight years old when she was sent for counselling because she was skipping school and spending her days and nights glued to her computer.

When she went back to school, she found it traumatic facing teachers and classmates again. It drove her back to her virtual world.

In her online game and fanfiction communities, she made friends, shared her digital artworks and felt more understood, though she often lost track of time and stayed up all night.

“On the internet, I could choose what to do, who to talk to and what to talk about,” recalled June, now 14. “No one could force me to do anything.”

Last month, the children and youth-focused NGO Hong Kong Playground Association (HKPA) interviewed more than 4,000 Hongkongers under the age of 18 and found 13.7 per cent with a high tendency towards online addiction. Among secondary school students, more than 15 per cent were found to be at high risk.

Summer holiday internet warning as online scammers prey on Hong Kong children

Frontline youth workers and scholars have called for a better understanding of online addiction, and for a more empathetic look at the psychological needs of children and teenagers displaying addictive online behaviour.

Experts say the signs of addiction include cravings, loss of control and individuals cutting themselves off from family and friends, as well as showing symptoms of withdrawal such as trembling and anxiety when they are not online.

Otherwise, although also worrying, youngsters might just be heavily relying on the internet.

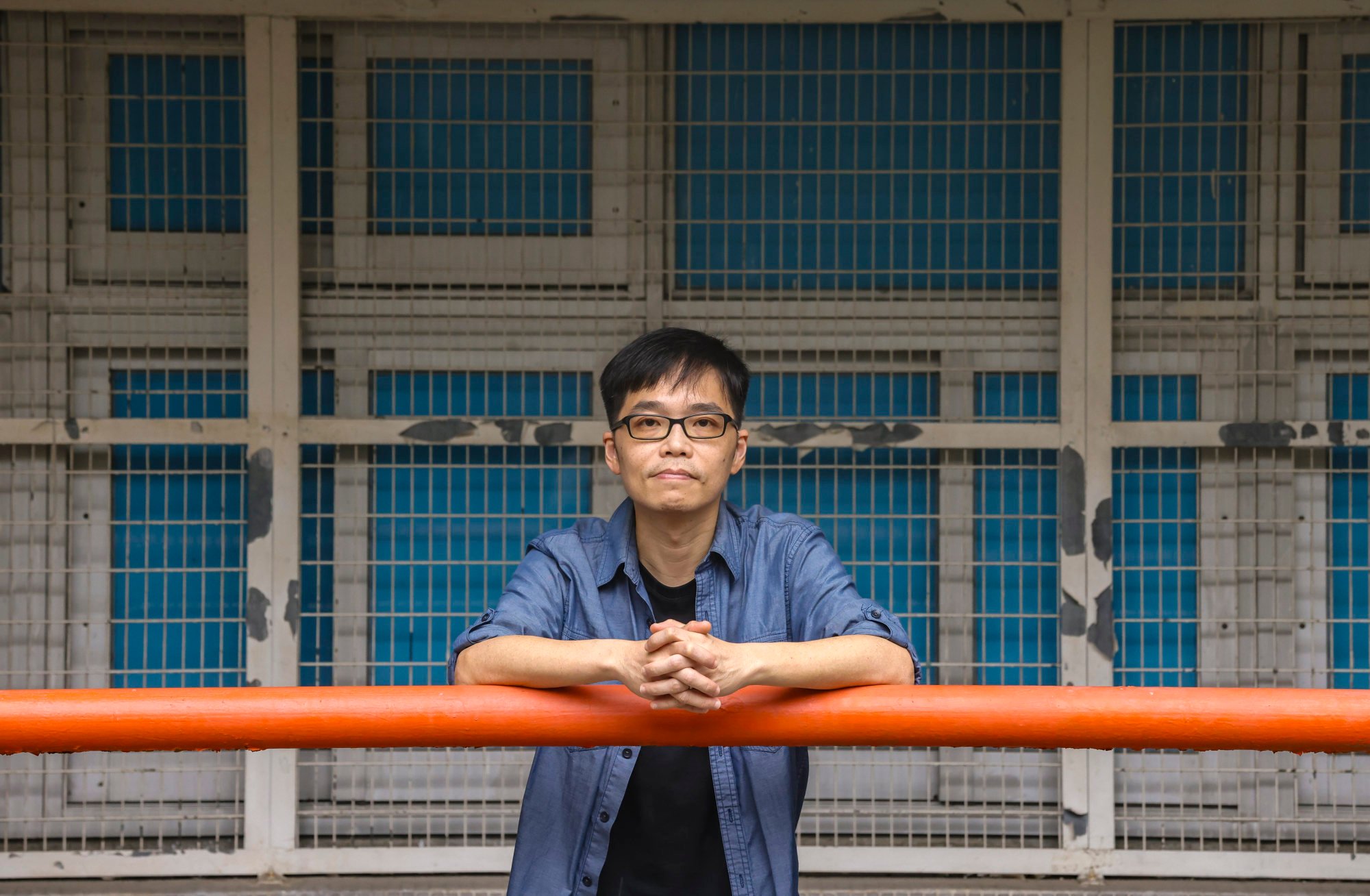

Joe Tang Chun-yu, who is in charge of Hong Kong Christian Service’s online addiction counselling centre, said troubles in real life lay behind many children’s addictive behaviour.

“I hope more people can understand that it is not necessarily an addiction, but an outcome of dissatisfaction with reality,” he said.

Children who spent a lot of time on the internet often did poorly in school, had no skill or talent, lacked peer support, which could all contribute to low self-esteem.

“They need friends, happiness, feelings of satisfaction,” he said. “They want someone to understand and accept them for who they are, but the real world cannot always fulfil those core needs.”

Tang said the centre’s counselling efforts focused on helping young people explore more choices, rebuild reality and find a balance in life.

“We prefer not to use the word ‘addiction’ because it carries a label, and also a lack of understanding towards the youngsters,” he said. “By using ‘imbalance’ instead, we hope to make them feel understood, accepted, and motivated to change their habits.”

June, who began going to the centre last year, gradually stepped out of her shell. Counselling and antidepressants from her psychiatrist have helped her deal with her social phobia.

Although she still spent an hour or two on the internet every day, she was no longer afraid to leave home or talk to people, and hoped to pursue her passion for digital art.

‘Trauma can last a lifetime’: backlash as Hong Kong mother withdraws smartphone

‘Loss of control a key feature’

HKPA project officer Venus Lee Yan-yi said parents worried about the amount of time their children spent online and their school grades, and this often led to clashes.

“If parents always assume using the internet is a bad thing, their children will avoid talking to them about it, even when they face cyber risks,” she said.

Addiction counsellor Chau Yuk-shan of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals’ Integrated Centre on Addiction Prevention and Treatment, said almost three in four of the young people he counselled were addicted to mobile gaming, experienced constant cravings and suffered many consequences including health problems and family conflicts.

Most struggled to understand their condition, and counselling focused on helping them realise the consequences.

About a quarter of those who came to the centre also had psychiatric disorders, including depression and autism, among others, he added.

The World Health Organization listed gaming disorder as a mental health condition in 2018, but debates remain over the diagnosis and definition of internet addiction, or excessive internet use.

Dr Chan Kai-tai, clinical associate professor of the University of Hong Kong’s department of psychiatry, said: “The definition of internet addiction varies across disciplines, but loss of control remains the core feature.”

He said it was important to set up a cross-disciplinary platform to understand internet addiction better and develop strategies to deal with it.

“As we talk about finding a balance in life, where exactly is the balance, and who gets to decide? Young people, who are the digital natives, should be involved in this discussion because they experience the biggest impact,” he said.

Instead of regulating screen time, he stressed that the focus should be on advocating healthy use of the internet, with a conscious boundary drawn between the physical and virtual worlds, and digital devices being treated as tools.

“We also have to be aware of, and widely discuss how digitalisation impacts humans as a whole before humanity becomes an artefact in the museums,” he added.

Professor Matthew Lee Kwok-on, chair professor of information systems and e-commerce at City University, who has been researching addiction in the past decade, believed it was part of a bigger problem in a new digital world.

“The Hong Kong population lacks digital literacy, meaning the right knowledge, skill and attitude to use digital technology … especially how to keep ourselves safe, including protecting privacy and our physical and mental health while using it,” he said.

‘A feeling she can’t process’: Hong Kong dad on helping child with mental health

He added there was a need for more research and education to cultivate healthy and productive use of technology.

“The key is to develop a self-regulation mechanism, so that individuals are aware of their behaviour and the potential consequences … and it’s important to acknowledge that the gadgets are not a scourge.”

*Name changed to protect interviewee’s identity.