‘A window into perspective’- How three European missionaries viewed the fall of the Ming empire and the rise of the Qing dynasty

- A new analysis of three travel writings offers a window into one of the most important moments in Chinese history

- But it is more valuable for the European perspective of events, rather than strictly factual Chinese history

It was one of the most important moments in Chinese history, when much of the 17th century was defined by war between the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and the Manchus, who in 1636 would officially become the Qing dynasty, China’s final imperial era.

“The best way to look at travel writing is as a ‘window into perspective’. The books show the reader some facts, but it depends on who wrote it and the circumstance under which it was written. Each writer will be stronger or weaker about certain events,” said Georg Schindler, a PhD candidate from the Ningbo campus of Nottingham University, who just published an article about the subject in the academic book Travel Writings on Asia.

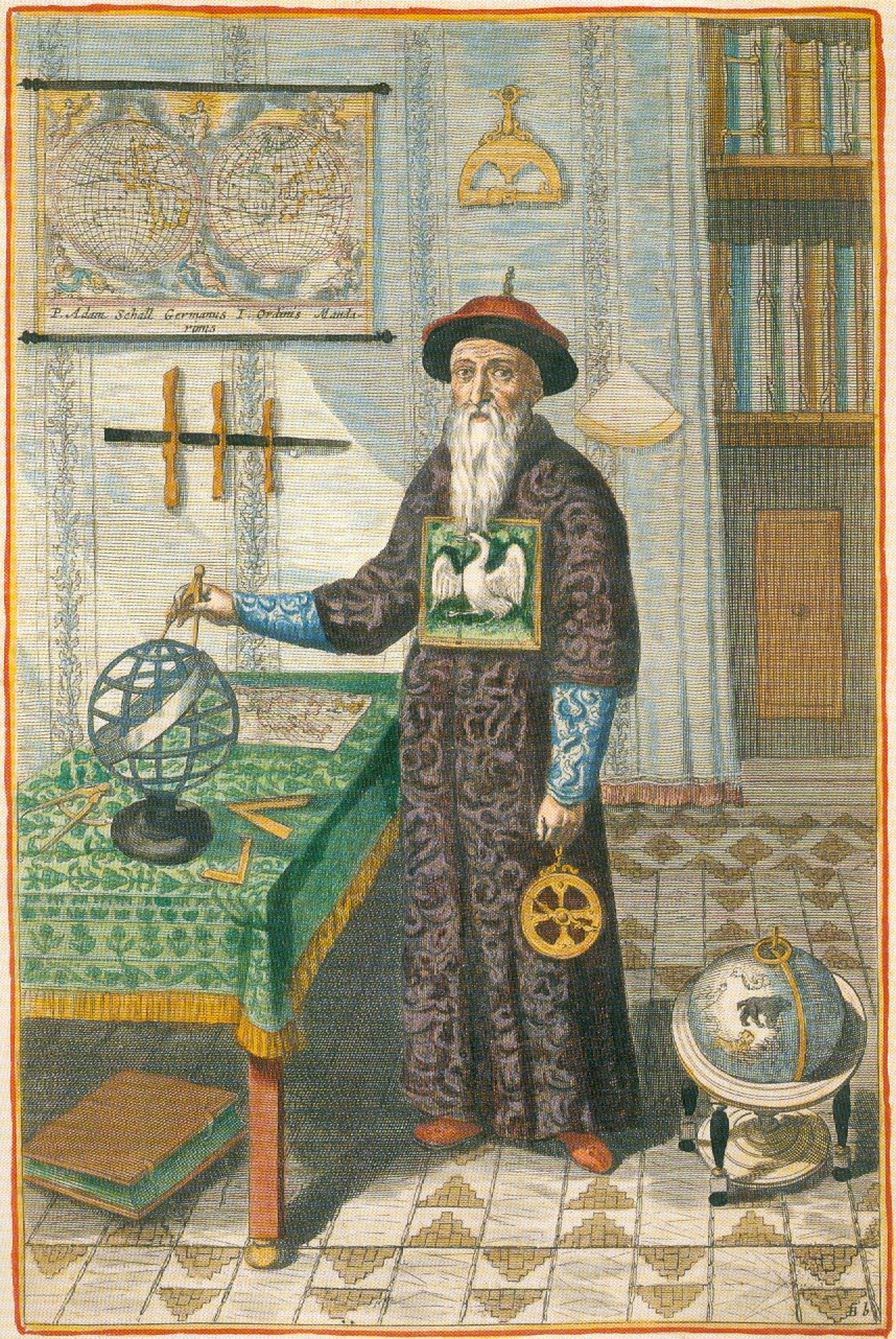

The research focuses on three main characters: Martino Martini, a Jesuit from what would become Italy; Johann Adam Schall von Bell, from today’s Germany; and Domingo Navarrete, a Spaniard.

Martini and Schall were sympathetic to the Manchus, albeit for slightly different reasons.

Martini travelled extensively throughout China, and saw the rise of the Qing dynasty as an opportunity to spread Christianity throughout the country.

Schall spent his time in the capital city of Beijing, and had a more narrow, albeit fairly accurate, perspective. He valued the Qing dynasty as a force of stability after the city had been sacked by Li Zicheng, a rebel leader who briefly served as emperor before the Manchus overthrew him.

Navarrete, on the other hand, was unsparingly critical of the Manchus, calling them a “tiger” that had “trampled down on all of China”. This viewpoint was driven by his personal experiences with the war with the southern Ming holdouts and the opinion that the Manchus were foreign invaders ruling China.

“Schall focused on the transition as a divine intervention that saved individuals, whereas Martini saw a larger plan. For Navarrete, he views the overthrow as a divine punishment and is focused on far older stereotypes,” said Schindler from Nottingham University.

But if there were a thread that tied the three together, it is their role as “diplomats for the church” because much of Europe at the time was obsessed with spreading Christianity worldwide.

Schindler said China played an exciting role in the imagination of European Christians, who recognised that the country had a huge cultural impact and that, if someone like a Chinese emperor became a Christian, it would create a domino effect across the region.

“The idea was, if China is converted, everyone else around it would also convert. China was the first step, so to speak,” said Schindler.

This mindset can be seen in Martini’s writing when he compared the Manchu conquest to a “flame that could be fanned in the wind”.

He viewed the rise of the Qing dynasty as an opportunity to spread the religion, and not only to ethnically Chinese people but also to the “Tartars”. Tarters was a broad term Europeans at that time used to describe northern people stretching from Ukraine to the far west of North Asia, which included the Manchus.

Martini’s optimism proved to be misguided. Even as short as five years later, other Europeans had given up hope of a quick conversion, republishing his books with more cynical titles and new introductions.

Was China compatible with Christianity?

It is impossible to look at this moment in history without understanding an intense debate in Europe during the 17th century about whether China was “compatible” with Christianity.

The crux of the argument was a disagreement over whether Confucian traditions were religious rites, or secular cultural customs with no religious overtones.

The Jesuits, who had a monopoly on Chinese missions in the 17th century, argued that values, such as honouring your ancestors, were secular and could be accommodated within the Christian faith.

Other orders, notably the Dominicans, of which Navarrete was a member, said Confucian traditions were religious rites, and thus violated a core tenant of Christianity to only pray to one God.

Called the Chinese Rites controversy, this debate dominated religious discussions about the European missions in East and Southeast Asia during the 17th century and impacted why our travel writers were making certain points.

Schindler said: “For the first time, the Pope says ‘You can no longer work the way you’re used to in China’. But the Jesuits did not want to change anything because they had begun to gain influence.”

He added that it was a bit of a historical coincidence that the controversy exploded just as the Ming dynasty fell apart.

Martini’s argument that the Qing dynasty was a flame should be interpreted as an argument that Jesuit accommodation was the best strategy for turning China into a Christian nation.

This kind of context was, for Schindler, the important takeaway from his work.

He said that, by learning about the authors, he could understand how three people could look at the same historical moment and come away with three entirely different perspectives.

“It was fascinating to see how much context mattered and how much time mattered. How much narratives changed,” said Schindler.