Pain or poverty? Foot binding tradition in Qing dynasty left Chinese women with tough dilemma

- For many women in ancient China, foot binding was the avenue to climbing up the socioeconomic ladder

- But it also eliminated any ability to be financially independent, helping to solidify a patriarchal society

Foot binding was a feature in Han Chinese society for a large swathe of its history and, in certain regions, was nearly ubiquitous for generations.

But because foot binding was not universal in China, it created an impossible decision for women, according to a recent study in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

Social tradition created a system that forced women to choose between: binding their feet and dramatically increasing the likelihood of marrying above their socioeconomic status, or avoiding the practice and achieving relative economic independence but spending their lives relatively poor and performing manual labour.

The team behind the study noted that, besides the physical deformity and pain caused by foot binding, these kinds of decisions were essential for keeping men atop a patriarchal society.

“Without foot binding, women could move around without physical difficulties and were able to engage in a lot of activities; thus, they did not need to depend on men for a living, but rather could be an important part of family labour-forces,” said Qian Wang, a professor at Texas A&M University who was part of the team performing the study.

This decision, which was typically made by parents for young girls between five and eight years old, was made possible because foot binding, which had started as a sign of elite status as early as the Tang dynasty (618-907), had trickled down to become a universal sign of beauty by the time of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

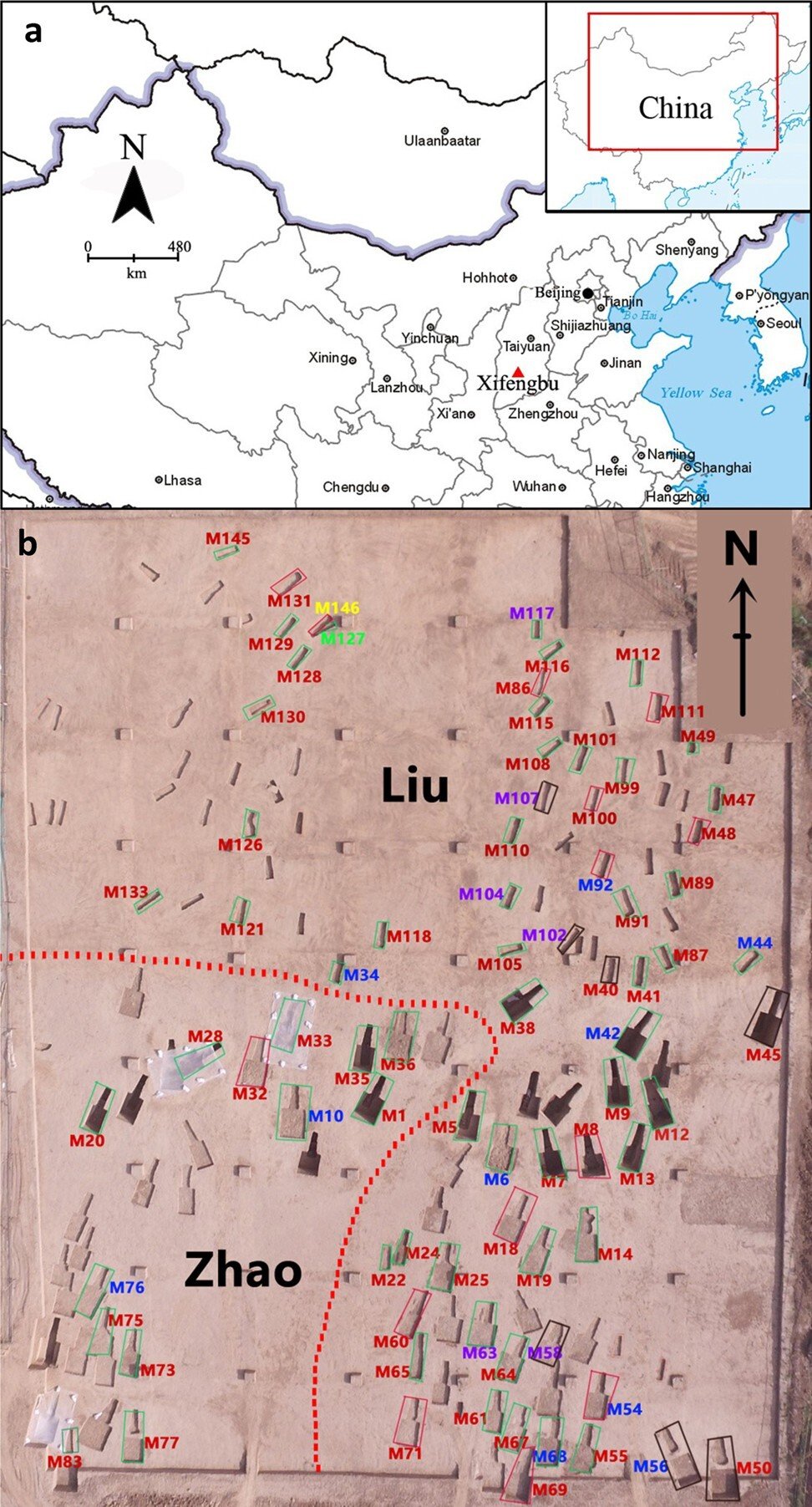

The study analysed a graveyard in Shanxi Province in central China excavated between November 2018 and July 2019. It was the familial burial grounds of two families, the Zhao and the Liu, and was used during the entirety of the Qing dynasty.

The team analysed 74 women, of which only 25 per cent did not have bound feet. Besides comparing the bones to examine the relative health of the women, they also investigated the burial objects to analyse the socioeconomic status of the person inside the grave.

“From this cemetery, non-foot bound women on average had less rich grave goods in the burials, indicating their families had relatively lower family wealth,” said Wang.

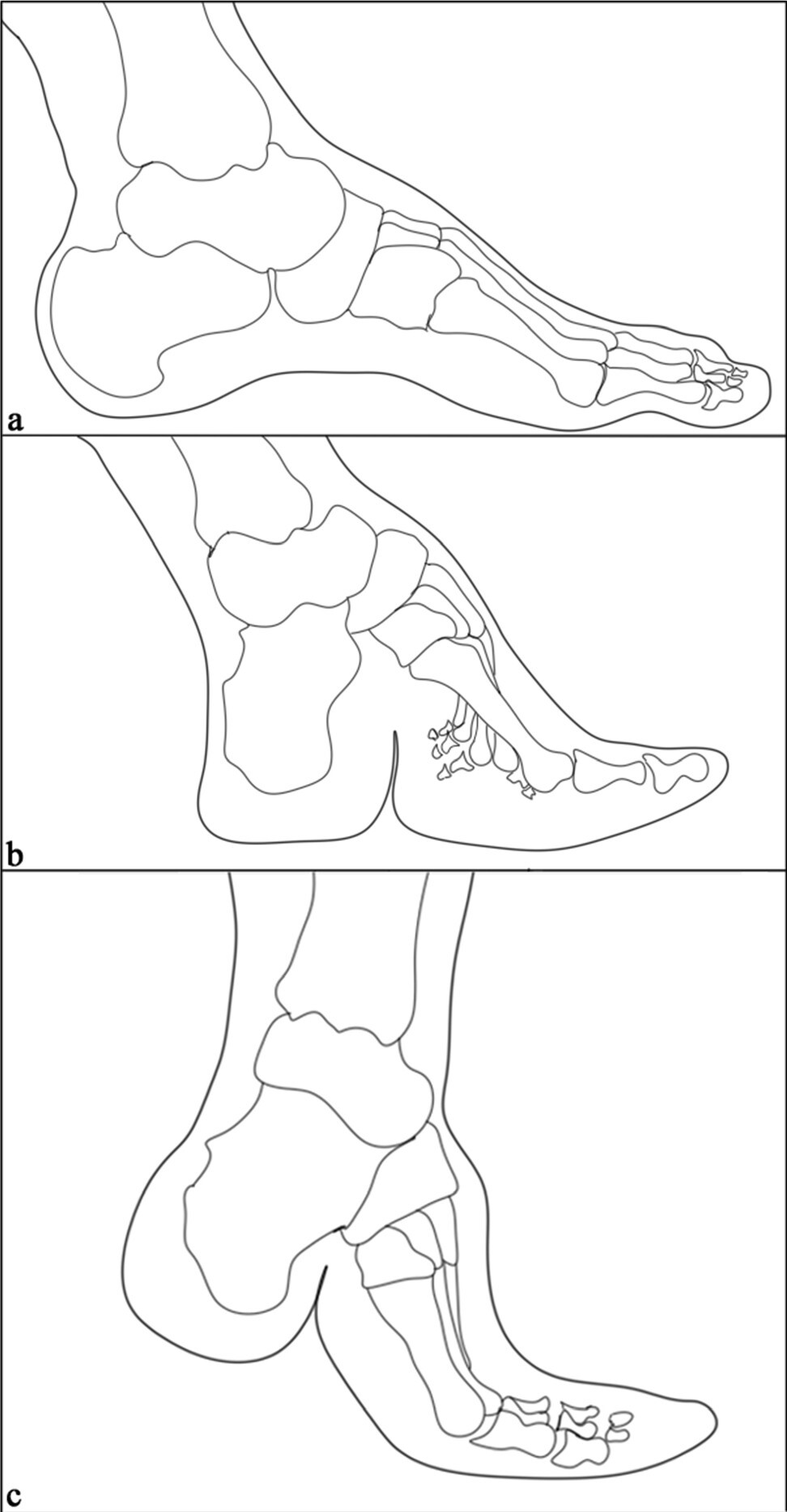

The physical limitations from foot binding were very real. Numerous studies have found that foot binding increased the likelihood of osteoporosis, traumatic arthritis and the risk of fractures from fragility. It also reduced mobility, made it harder for women to sit and stand, and many skeletons showed signs of serious degenerative joint diseases.

The study cited in this article was the first known analysis of the limb bones above the foot, and it found the tibiae and fibulae were smaller, thinner and were “remarkably different from those of the non-binding group”.

“It is believed that the loss of working ability in foot binding women, plus their dependence on their husband and family for wealth, can be regarded as a sign of familial wealth,” the authors wrote.

In a historical quirk, there was a period during the Ming dynasty when a proliferation of cotton might have increased foot binding because it eliminated the “peasant’s dilemma”. Women could find work as seamstresses or other jobs in textiles that did not require them to be on their feet, thus allowing them to work but also have bound feet to make them more attractive for marriage.

However, the influx of foreign textiles after the First Opium War (1839-1842) diminished the value of labour by women with bound feet.

During the Qing dynasty, the ability for non-foot bound women to avoid a life of inconvenience and achieve a relative degree of economic freedom was accepted by the rural parts of China, the authors wrote.

“The presence of non-foot bound females in the [Shanxi] cemetery indicates the value of non-foot binding in ancient China while the tradition of foot binding prevailed.”

Once again, this reality foregrounds Han Chinese women’s decision: enter a lifestyle with minimal physical demand, or choose economic independence even if it leads to a more challenging life.

Without foot binding, women could move around without physical difficulties and were able to engage in a lot of activities.

Toward the end of the Qing dynasty, foot binding was on its way out, driven by the government, political factors and “awakening waves” among women at the time.

“There were examples of high-class women without foot binding because their families held the opinion opposing foot binding,” said Wang. “A late example is Kang Youwei – a prominent thinker and reformer of the late Qing dynasty – who did not have her daughters’ feet bound.”

The practice was outlawed in 1912, but some women continued to do it in secret until about 1949, when the Chinese Communist Party took control of China.