The Oscars of Archaeology: China unveils its top 10 discoveries of 2023

- One discovery unearthed some of the oldest people to ever live in China

- While another used extremely modern technology to create a breakthrough

Every industry has that one annual event that stands apart as the premier award ceremony.

For Chinese archaeologists, the best discoveries of the year awarded by China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration is the industry’s Oscars.

The agency says it looks for revelations that “inspire important discussions, offer new perspectives, and take archaeology in a novel direction.”

“The projects selected as the ‘top 10 new archaeological discoveries’ in 2023 are outstanding representatives of field archaeological work from the past year. These new archaeological discoveries vividly demonstrate China’s long history and vast civilisation and are the foundation of self-confidence and a source of strength,” the agency said in its announcement.

The projects range from uncovering prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies to surveying beautiful porcelain cerematics work, and even include a great achievement in China’s burgeoning industry of underwater archaeology.

This year’s crop also happens to be a particularly old set of sites, with only two coming from after the BC-AD timeline shift.

It is important to note that many of the recipients were rewarded for the artefacts discovered over the course of years-long excavation projects, and most of the sites were first discovered prior to 2023.

So here they are, the “Oscars of Archaeology” – the National Cultural Heritage Administration’s top 10 most important excavations of 2023.

The first time Chinese people harnessed water

The Qujialing relics in the central Chinese province of Hubei are crucial because they represent the earliest known example of people in China harnessing water, rather than simply trying to contain it.

The Qujialing dam was built around 5,100 years ago and was about 2 metres tall and 180 metres long. The people also created a full reservoir and spillway. The details of the site indicate that the dam was built to preserve water for long-term use rather than to prevent flooding.

This site represents a transition from “passive water control” to humans in the area actively transforming the nearby landscape to harness the power of water.

Interestingly the dam is unique and does not exist in peer regional civilisations, suggesting that these people had made a technological leap compared to their neighbours.

Large-scale sacrifices at a dynasty’s birthplace

Archaeologists working in Gansu province in northcentral China discovered a massive complex at the Sijiaoping Ruins that they believe was used for sacrifices.

The 28,000-square-metre complex was symmetrical and included a large platform, likely for the executions, as well as various annexes. The facility is the first Qin dynasty (221-207 BC) building described by archaeologists as being “systematic”.

The scientists described a “half-crypt” that they believe was filled with water to create a pool in line with the Qin-era belief in the “virtues of water”. The team working on the site described the discovery as creating a “sense of grandeur and solemnity”.

The region is believed to have been where the Qin dynasty was born.

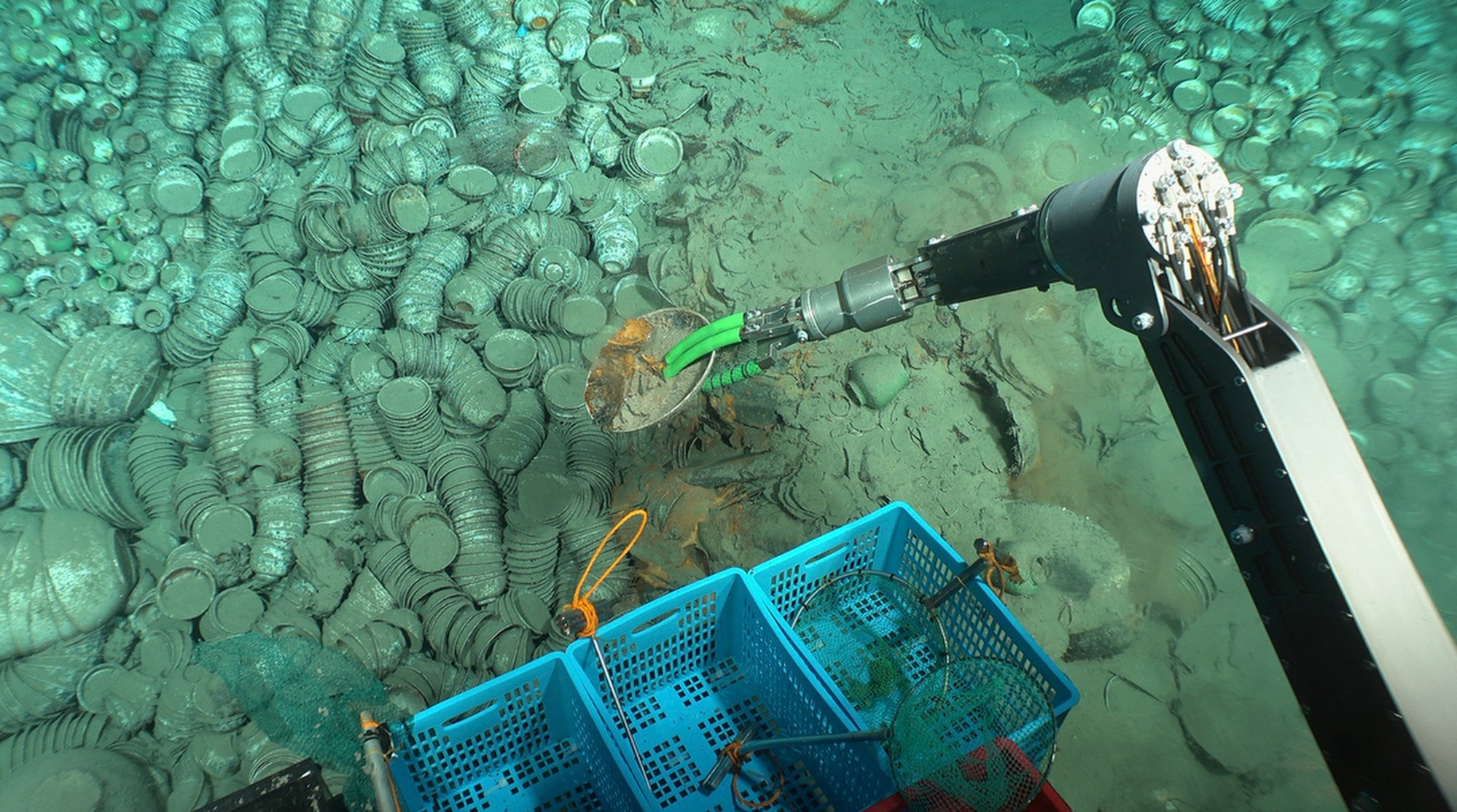

Excavation of two shipwrecks represents a major technological breakthrough

Two shipwrecks dated to the middle of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) were less important for what was found, but rather how they were discovered.

The ships were found 1,500 metres below the surface in the South China Sea off the coast of the southern island province of Hainan, and their excavations represented the first time China had successfully pulled off a deep-sea archaeological mission.

Scientists will complete around 50 diving trips to explore the two ships over the next three years using various submersibles.

China’s burgeoning underwater archaeological programme had previously focused on shallow waters, so discovering the Ming-era ships represent a major breakthrough for the country.

A cemetery from Shang dynasty nobility

Archaeologists discovered a family cemetery in central China’s Henan province believed to have belonged to high-ranking aristocrats who lived during the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BC).

The cemetery featured 28 tombs of various sizes, and three of them included a character that looked like the modern Chinese character for zhong, which means “centre”. They also found sacrificial pits for humans, horses and cattle around the tombs.

While archaeologists disagree about when the Shang dynasty began, it is the oldest known Chinese dynasty that is supported by historical proof.

The Shang-era people created the oracle bones, which showcase the earliest examples of Chinese writing.

Discovering a vibrant hub of one of China’s earliest dynasties

The 3,200-year-old settlement at Qingjian Zhaigou in Shaanxi province in central China revealed a vibrant town with stunning artefacts and rammed-earth buildings at a large scale. The scientists discovered bronze chariots and horses as well as many pieces of jade ware, bone ware, lacquerware and transformed tortoise shells.

The discoveries point to a highly developed bronze age civilisation in the northern regions of Shaanxi that likely was a centre of trade for other regions of the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BC).

The Shang dynasty was commonly referenced in classical Chinese literature, and confirmation of its existence was largely thanks to people living during the Song dynasty (960–1279) who kept and described Shang dynasty bronze artefacts.

Unearthing the earliest China inhabitants

The Bashan Site Complex in eastern China’s Shandong province includes 80 different sites, and its discovery came after a large dam downstream discharged a significant volume of water to reveal the artefacts in 2020.

The site is estimated to be between 50,000 and 100,000 years old, and archaeologists said they found stone tools near fossils from large mammals, including a shovel-shaped tool made from straight-tusked elephants, the first such artefact found in China.

The site contains tens of thousands of relics that are essential evidence for understanding the lives of the earliest people to inhabit China.

New evidence about Austronesian migration

The Keqiutou Site sits on an island named Pingtan in Fujian province in southeast China and is estimated to be between 6,500 and 7,300 years old.

The Austronesian people were widely believed to have inhabited Taiwan before they began a mass migration south, where they would eventually spread throughout Southeast Asia and become the ancestors of a population of 400 million people today.

The new evidence suggests that those people migrated using multiple routes, one of which may have included the eastern coast of mainland China.

An ancient town with 4,000 years of history

The excavation of the Mopanshan Site in central China’s Anhui province has become a bottomless well of cultural artefacts, illuminating life in China before the dawn of the Qin dynasty (221-207 BC).

Scientists have found artefacts from the time of the Xia dynasty (2070-1600 BC) – an empire that may not have existed – all the way till the end of the Warring States period (476-221 BC).

The site is rare because it is an ancient town in the lower Yangtze River that showcases evidence of 4,000 years of continuous inhabitation.

Over the three excavations (2015, 2016, 2023), scientists have unearthed 343 tombs and 4,000 artefacts. Scientists announced in March that they had started a fourth excavation of the site to be completed in 2024.

An eastern culture spreads inland

The neolithic Wangzhuang Site, located in central China’s Henan province, revealed new evidence about the Dawenkou Culture, including the rare discovery of a cemetery associated with the people.

The discovery of a significant Dawenkou community in central China indicates that the population – which mostly lived in Shandong province in eastern China – had spread inland. The people are known for the practice of teeth removal and cranial deformation as a part of their culture.

The artefacts included pottery, jade wares, and stonewares that offered insights into the cultural practices of the Dawenkou people.

How ceramics continued to develop after the golden age

China is known worldwide for its ceramics and porcelain wares, and rare pieces can sell for millions of US dollars.

Archaeologists on the search for the ceramic hubs discovered one at a site in Chencun, in Shanxi in central China. It spanned three dynasties – the Jin (1115-1234), Yuan (1271-1368) and Ming (1368-1644) – and once became the last breath of white porcelain manufacturing in the region.

The team excavated a kiln complex that featured bun-shaped kilns and brick caves meant for drying wares that did not require firing. The complex helped archaeologists learn about how porcelain developed after it took off during the Song dynasty (960-1279).