Failure to name China as focus of strengthened CFIUS investment panel ‘could lead to abuse and loss of money’

Failure to name China in legislation is faulted for its possible effect on acquisitions by companies from other nations

The US government was warned on Tuesday that its reticence to name China in foreign investment legislation could lead to “abuse” and a drop in money coming in from other countries.

Last week Congress moved to strengthen and expand the powers of the inter-agency Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), a decades-old entity that reviews foreign corporations and their American investments for national security considerations, following concerns from lawmakers about the intentions of Chinese technology companies and the potential threat they posed.

But on Tuesday, numerous industry representatives and foreign-policy experts said that the vagueness of the legislation’s wording – and the failure to mention China as the target of increased scrutiny – could chill investment overall in the US, and not just from China.

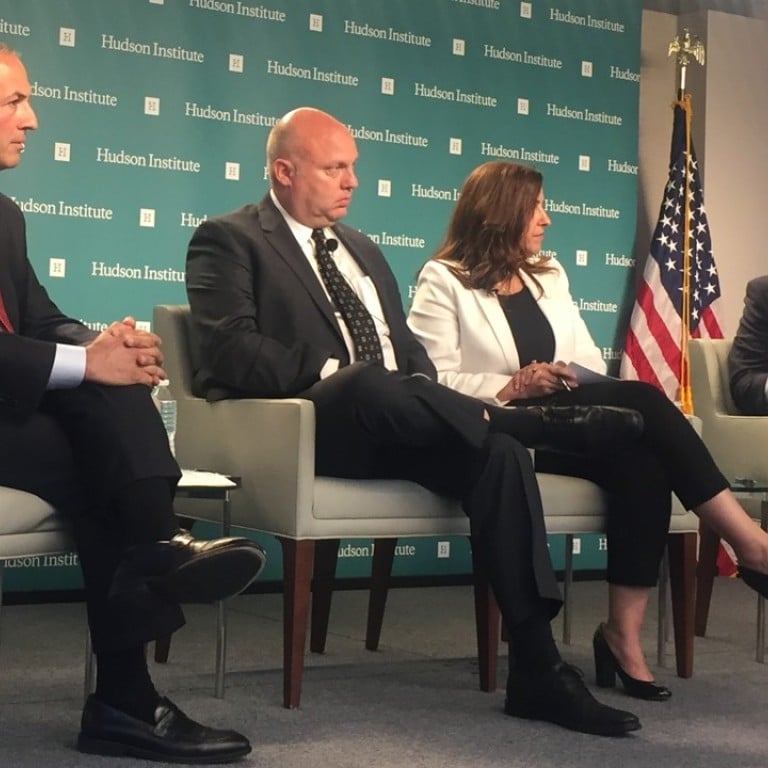

Speaking at a Hudson Institute forum, Mario Mancuso, the former undersecretary of commerce in the George W. Bush administration, said that not mentioning China in the CFIUS legislation might also disadvantage non-Chinese international investors bidding for businesses in the US.

“A seller of a US business – by virtue of the fact that you are foreign – may just decide not to sell to you because they don’t want to deal with the regulatory overhang,” said Mancuso, who now leads the international trade and national security practice at Kirkland & Ellis.

Changes to CFIUS, as laid out in the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernisation Act, expands the reach of the committee’s scrutiny from merely direct foreign investment for controlling interest in a US company to include joint ventures and foreign investments that result in any level of control.

The measure, which passed both houses of Congress, now awaits only President Donald Trump’s approval.

Derek Scissors, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute who testified several times during the CFIUS bill’s formulation, said that the lack of any reference to China within the act itself could also make the new committee vulnerable to misuse.

“The current CFIUS language lends itself to future abuse,” he said. “You need to define what CFIUS is doing really precisely. Otherwise, 10 years from now you’re going to find it’s a tool to do things you do not want to do – even five years from now.”

Nancy McLernon, the president of the Organisation for International Investment, a trade group representing the US-based subsidiaries of foreign corporations that has backed the reforms, acknowledged that it was past time to update the CFIUS authority.

“The last time CFIUS reform was done was when Miley Cyrus was touring as Hannah Montana” in the 2000s, McLernon said.

Even so, she voiced concerns that an increase in the committee’s power could further the protectionist agenda of the Trump administration, which supports the new CFIUS.

“In an administration where economic security is one and the same with national security, there are concerns in terms of how this administration might implement regulations,” said McLernon.

Even before these reforms, McLernon said, “deals have been scuttled already because a US competitor used the CFIUS process as a wedge in a commercial environment”.

As an example, McLernon recalled how, in 2006, the Dubai-owned DP World bought rights to terminal operations at six American ports, only to face stiff congressional opposition. Eventually it had to hand over operations to an American company.

Alongside the lack of any stipulation regarding the target of the tightened rules, Scissors also said that the reforms do not go far enough in terms of specifying what kinds of technology will raise red flags for the committee.

“You cannot be running around talking about ‘critical’ technologies and ‘breakthrough’ technologies and ‘frontier’ technologies,” he said. “You have got to tell people what the hell you’re saying.”

“‘Critical’ can be abused; and even if it’s not abused, you paralyse too many companies with trying to decide what a critical technology is.”