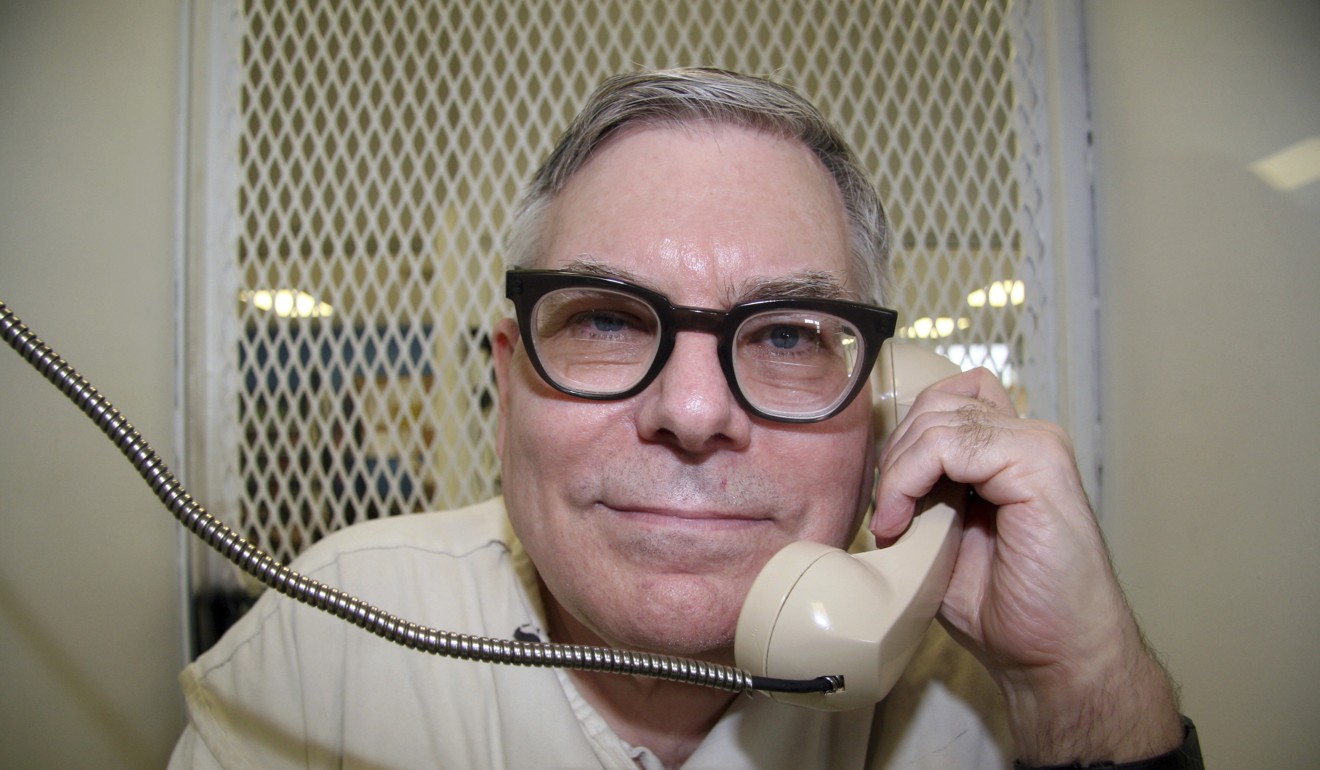

This reporter has watched more than 400 executions: ‘The job is to tell the story’

Michael Graczyk has watched 429 executions in Texas as a reporter for the Associated Press in Texas

After a last meal of hamburger and fries washed down with Dr Pepper, James “Cowboy” Autry was put to death in 1984 for shooting a shop assistant between the eyes when she asked him to pay US$2.70 for a six-pack of beer.

Autry was the fourteenth person in the US, and the second in Texas, to be executed since the US supreme court reinstated the death penalty in 1976.

The 29-year-old, who told a reporter he would have preferred to die by hanging or beheading because lethal injections “ain’t manly”, asked for the event to be televised.

Michael Graczyk, though, was present, chronicling Autry’s demise for the Associated Press.

Based in Michigan, which does not have the death penalty, Graczyk never imagined he would see an execution. Then he was transferred to Texas. Of the 1,479 US executions in the modern era, Texas has carried out 553. By one count, Graczyk has watched 429 of them: far more than any other American.

“I would be tempted to describe him as the dean of reporters covering executions but the fact is there’s nobody else even in the same school. He’s witnessed 80 per cent of the executions in the most prolific executing state in the United States,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Centre.

Now 68, Graczyk retired at the end of July but will continue to cover executions for the news agency as a freelancer. Autry’s was his first. “I was assigned to do a first-person account of what it’s like to be in the death chamber,” Graczyk said in an interview at his home between Houston and the state penitentiary in Huntsville. “They now have a Plexiglas window which you look through and there are jail bars but back then all it was, was a metal rail that separated you from the inmate,” he said.

Graczyk was one of up to five media witnesses standing in the tiny viewing room as the injection is administered.

Prisoners are usually resigned to their fate and the scene is typically calm and quiet, he said, though he recalls the revving of motorcycles by pro-law enforcement bikers who gather outside for the death of a cop killer, and the nights when a storm rolls in and thunder booms as the dose takes effect.

He recalls that when asked for his last words, one prisoner spat out a handcuff key which he’d seemingly kept hidden under his tongue all day.

Two inmates he had interviewed greeted him from the gurney when he walked into the chamber. “Hi Mike, how you doin’? I look like a stretched out goose, don’t I?” said Robert Black, executed in 1992 for hiring a hitman to kill his wife. “What are you supposed to say, how do you respond? I was totally at a loss. I didn’t say anything,” Graczyk said.

Occasionally, family and friends are overwhelmed. “The mother of an inmate collapsed right down at my feet, hyperventilating. Brother of an inmate kicked a hole in the wall because he was so upset. They’ll pray or sing or offer some sort of comforting, ‘I love you’ kind of stuff to the inmates,” Graczyk said.

“At some point a physician comes in, does a kind of cursory examination – shine light in eyes, check for heartbeat, look at the clock on the wall and give you the time, that’s how it ends.”

Graczyk then rushes across the street to file his copy from the press room.

The death penalty is enacted less frequently and by fewer states than in the past, and public support for it is declining.

Texas has executed eight prisoners so far this year out of 14 nationwide, compared with its 40 judicial killings out of 85 across the country in 2000. But the role of media witnesses is arguably more important than ever as some states have sought to reduce transparency in the wake of botched executions and ongoing questions about drug supplies from shady sources that critics say place inmates at risk of torturous deaths.

“As the states respond by retreating farther and farther into secrecy the need for witnesses becomes even more important as the process becomes less and less trustworthy,” Dunham said.

Asked for his view on capital punishment, Graczyk said that an impartial stance helps him professionally when he interviews attorneys, offenders and victims’ families. “I’m not dodging the question, but I don’t know. I think that it’s in my advantage to not take one side over the other,” he said.

He does not lose sleep over what he has seen. “I don’t know these people, I don’t have an emotional attachment to them. They’re not my loved ones, either the victims or the inmates. I think that’s part of the process that makes it easier for me,” he said.

Still, he added: “The one case that kind of comes back again and again is a guy named Jonathan Nobles [in 1998]. As they started doing the drugs he began singing Silent Night, the Christmas hymn – and it’s nowhere near Christmas. And when he got to ‘round yon virgin mother and child’ he stopped, he slipped into unconsciousness.

“I’m in church on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day and you’re surrounded by all these people in the joy of the season singing Silent Night and I’m standing there and you get this flash of Jonathan Nobles. That’s the one that really comes back.”