Relax, China’s economy is not headed for a crisis

- While it would help if Chinese households saved less and spent more, the economy is probably in a much better position than the pessimists claim

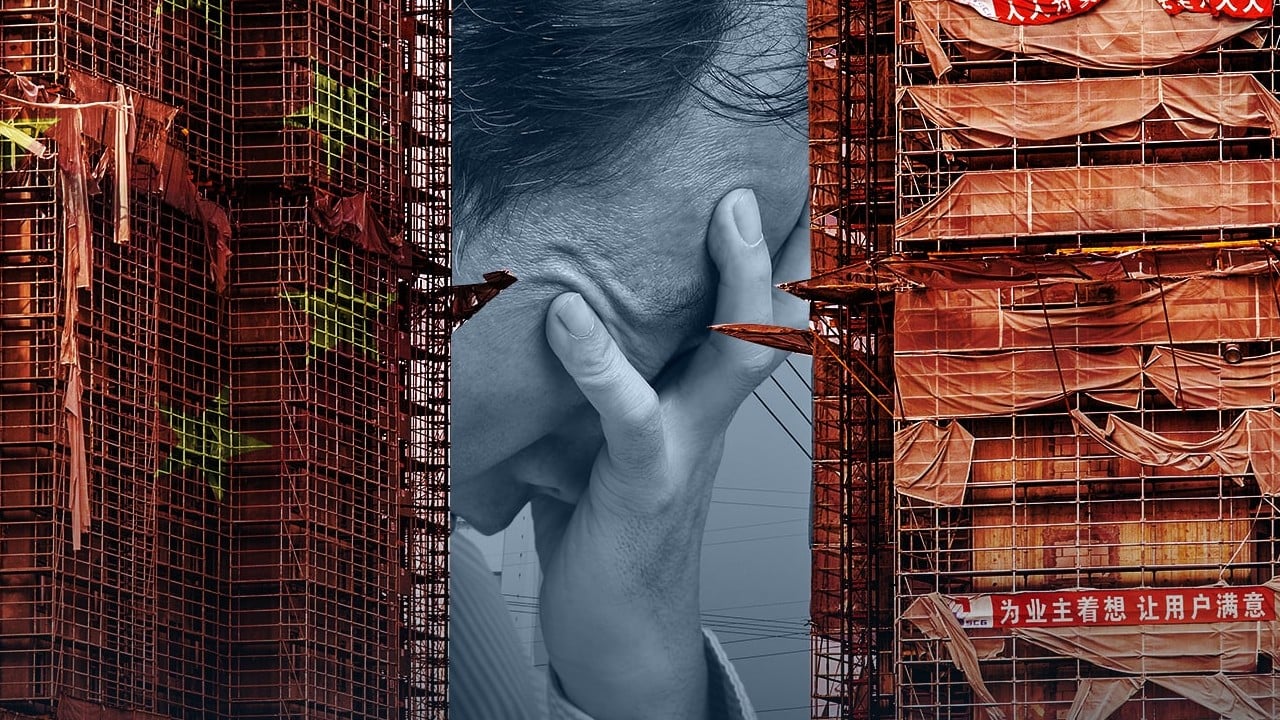

Economists have lately been sounding the alarm that China’s economic development is teetering on the edge of a crisis. The problem, they argue, is that China’s growth is driven by extremely high levels of capital investment, and that private consumption is being suppressed. Is a crisis really looming?

It is true that China’s growth pattern could, for decades, be characterised as investment-driven. Like most East Asian economies, China supported development by leveraging its high savings rate to maintain very high investment, and policymakers often used infrastructure spending as a countercyclical policy instrument.

In 2009, for example, China’s government introduced a 4 trillion yuan stimulus plan to offset the adverse effects of the 2008 global economic crisis. By the end of that year, China’s rate of investment growth had surged to 30.1 per cent, with total investment reaching 45 per cent of gross domestic product.

But China withdrew fiscal stimulus in 2011 to contain a swelling real-estate bubble and mitigate the threat of inflation. Investment growth has fallen steadily ever since, amounting to just 3 per cent last year, and has been largely outpaced by GDP growth since 2017.

To be sure, China’s final consumption expenditure is much lower than that of the United States – 56 per cent of GDP, compared to 81.5 per cent of GDP, in 2019. But the structure of consumption is very different: services constitute less than 50 per cent of final consumption in China, compared to two-thirds in the US.

Furthermore, service prices are much lower in China. After adjusting for the price difference, I found that, in 2022, total consumption expenditure on goods (including catering) in China was 37 per cent of GDP, compared to 28 per cent in the US.

In other words, when it comes to goods, China out-consumes the US (as a share of GDP). Reinforcing this assessment, China’s consumer-loan-to-GDP ratio (not including mortgages) was 14 per cent in 2022, roughly as high as the ratios in the US and Japan.

Then there is home ownership. Over the last several decades, Chinese households have spent a very large proportion of their incomes on housing purchases. As a result, China’s home ownership rate today is among the highest in the world. (China’s floor space per capita is also very high.)

I see no fundamental difference between buying expensive consumer goods and buying a house to live in, but the former is counted as consumption and the latter as investment. And when it comes to real-estate investment, China’s rate is among the world’s highest (as a share of GDP).

The bureau’s flow-of-funds table – which is published less often and gets less attention than the survey data – indicates that China’s household disposable income amounted to about 60 per cent of GDP in 2019. There is good reason to think this is the more accurate figure.

Notably, total government revenue as a share of GDP has hovered in the 20-30 per cent range over the last decade – among the lowest rates among major economies. Both government revenue and household disposable income cannot possibly represent such a small share of GDP.

Consumption is, after all, a function of income, income expectations and wealth. That is why the first step towards boosting consumption is jump-starting growth, which requires a new wave of government-financed infrastructure investment.

This bond issuance is a test case for China. If it is successful, the government might issue more bonds to finance infrastructure investment to offset the adverse growth impact of slowing consumption growth and falling real-estate investment. The government also needs to raise more money to stabilise the housing market and alleviate local governments’ debt burden.