Sex, Olympism and why Rio is set to be a ‘reasonably epic’ disaster

For much of its modern history, the Olympics has been a study in the contrasts of inspiring vision alongside grubby reality

It was summer 1976, and I was cutting journalistic teeth with the Sunday Mirror in Manchester. Suddenly the news editor, of whom I was obviously in awe, had a bright idea: go out into the streets of Manchester with a photographer and interview married women about how the Montreal Olympics were affecting their sex lives.

If you are not cringing, then I certainly was. The idea of randomly approaching women on the street to talk to them about their sex lives looked like a fast track to many slaps in the face. Today, the innocent and refreshing thing about this first journalistic encounter with the Olympic movement was that, for the editor of the Sunday Mirror, was the most controversial angle he could think of. Today he would be spoiled for choice, between drug scandals, condom shortages in the Olympic village, the Zika virus and life-threatening pollution in Guanabara Bay, home to all the Olympic water sporting events. Already, the Australian Olympic team has been robbed, and members of the 412-strong China team came face to face with a shooting.

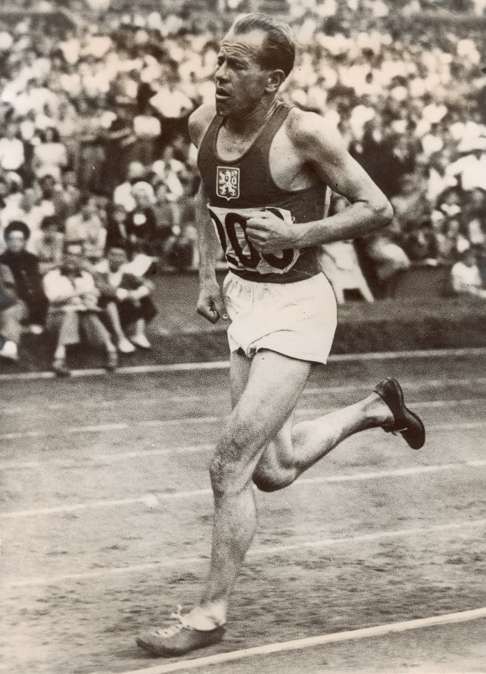

For a movement with such high-minded aspirations, the modern Olympics have since those first Athens Olympics in the Panathinaiko stadium in 1896 developed a rather dog-eared track record. Count Pierre de Coubertin, generally regarded as the main driver for the resurrection of the Olympic movement, insisted that “the important thing is not the triumph, but the struggle… not to have conquered, but to have fought well”. As a century has passed, the struggle has made for occasional good copy, but the triumph has been what the games was all about – demonstrations of national virility, assertions of global hegemonic power. The humble, awe-inspiring dedication of the Czech army officer Emil Zatopek literally running away with the 5,000 metre, 10,000 metre, and marathon golds in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics is an exception that proves an otherwise tawdry rule of rising commercialization, corruption and drug-enhanced performance. With a slogan of “Citius, Altius, Fortius” – “swifter, higher, stronger” – there was perhaps always a conflict between the grubby reality of the games and the inspiring vision of Olympism.

As a journalist for the Financial Times working mainly in Asia, I must confess that since that first 1976 flirtation with Olympic news reporting, the various Olympics have since then rather passed me by. I was always in the wrong part of the world, in the wrong time zone, and focused on the wrong issues to get very excited about those 17 days of testosterone-laced combat. The Palestinian murder of 11 Israeli athletes in the 1972 Munich Olympics obviously caught my attention, as did the infamous Black Power salute in Mexico City in 1968. The African boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics, followed by the 1980 boycott of the Moscow games in protest at Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan, also caught my attention, but only for bad reasons.

Another abiding theme that colours every summer Olympics, alongside the extravagant commercialization, is the chronic failure to earn money. The cycle is persistently the same during the seven years between choosing the Olympic host, up to the event itself. The initial promise is of shopaholic visitors, packed hotels, an advertising bonanza, and iconic new infrastructure investments. The final audit almost always shows awesome losses. On average a summer Olympics seems to cost around US$10 billion in today’s dollars, and tends to earn about US$8 billion – original revenues of around US$4 billion, US$1 billion in ticket sales, US$1 billion from sponsors, US$1 billion from broadcast rights, and a final US$1 billion from the city’s share of the Olympic Committee’s global broadcast earnings. The cheapest on record is deemed to be Atlanta in 1996, which cost US$3.6 billion, and the most expensive by far was Beijing in 2008, which cost an estimated US$45 billion. After extravagantly fudging the numbers with “spillover benefits”, the 2012 London Olympics cost US$13 billion – four times the original budgeted cost. In the 1998 Nagano winter Olympics, the numbers were so awful that the financial records were “accidentally” burned.

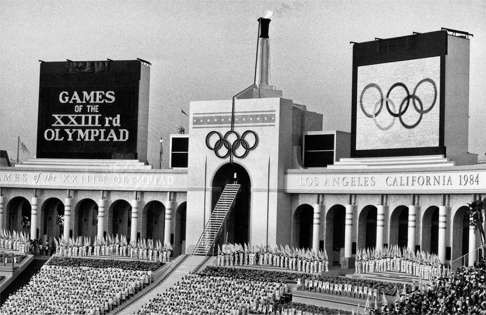

Only two Olympics have undisputedly turned a profit – both of them in Los Angeles, first in 1932 and then in 1984. The key lessons on how to make a profit? Bid for the Olympics during a recession; bid low after a disastrous games (Los Angeles 1984 followed the boycotted Moscow games); be a “hidden gem” of a city that can leverage the games to introduce itself to the world (like Barcelona in 1992); use the same Olympic facilities twice; and make sure you do everything on the cheap.

I was always in the wrong part of the world, in the wrong time zone, and focused on the wrong issues to get very excited about those 17 days of testosterone-laced combat

By these many measures, the Rio Olympics look set to be a disaster of reasonably epic proportions. Venues and the metro system are incomplete. The ocean is polluted. Zika haunts every nook and cranny. The country is buried in its worst recession for almost a century. And suspended President Dilma Roussef’s impeachment shows a country in political chaos. The doping scandals that are keeping so many Russian athletes away are not of Brazil’s making, but coming in the wake of corruption scandals in Fifa and doping scandals in other sports like cycling, they have tainted the games. So many today question how many of the medals have been won on the back of chemical enhancement. From the shaming of sprinter Ben Johnson in the 1988 Seoul Olympics, doping scandals have become graver and graver. A widely-quoted study in Sports Medicine estimates that between 14 and 39 per cent of athletes dope. Whatever the true number, the suspicion of winners tarnishes even the most awesome of performances. Whether it is the dominant teams coming from the US, Germany, Brazil, Germany or China (all with more than 400 competitors), or little teams like that from Hong Kong, which is just 37-strong, and has only ever won one medal, potential drug scandals hover not far away.

But going back to my Sunday Mirror sortie onto the streets of Manchester, you may be interested to know that I did not get my face slapped once, and that a surprisingly large number of married women were willing to talk to a stranger about the uplifting influence of the Olympics on their sex lives. That seems to be true for the athletes too. For the 17-day event, athletes are issued with 51 condoms apiece – three a day. And even then, stocks are said to run out. Despite all of the unhappy things that journalists focus on, it seems that many athletes take the “Citius, Altius, Fortius” mantra both seriously and literally – both on the field and off.

David Dodwell is executive director of the Hong Kong-Apec Trade Policy Group