For HK$55 a night, Hong Kong’s ‘invisible homeless’ or working poor turn to cybercafes, amid unaffordable rents and with nowhere to go

- Air conditioning and desktops for internet are better options than squalid, bug-infested subdivided flats or 24-hour fast-food chains

- Social workers urge government to adopt a more centralised policy in tackling the problem and providing social housing

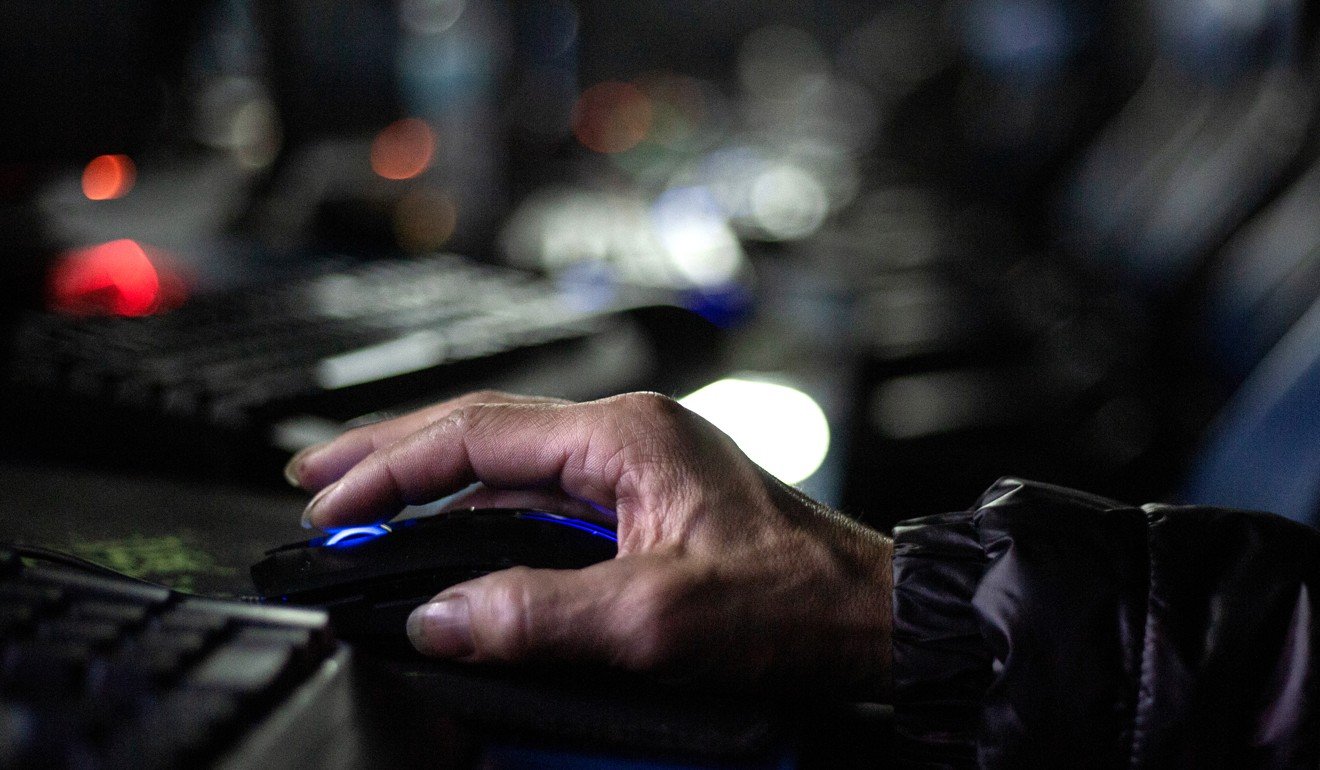

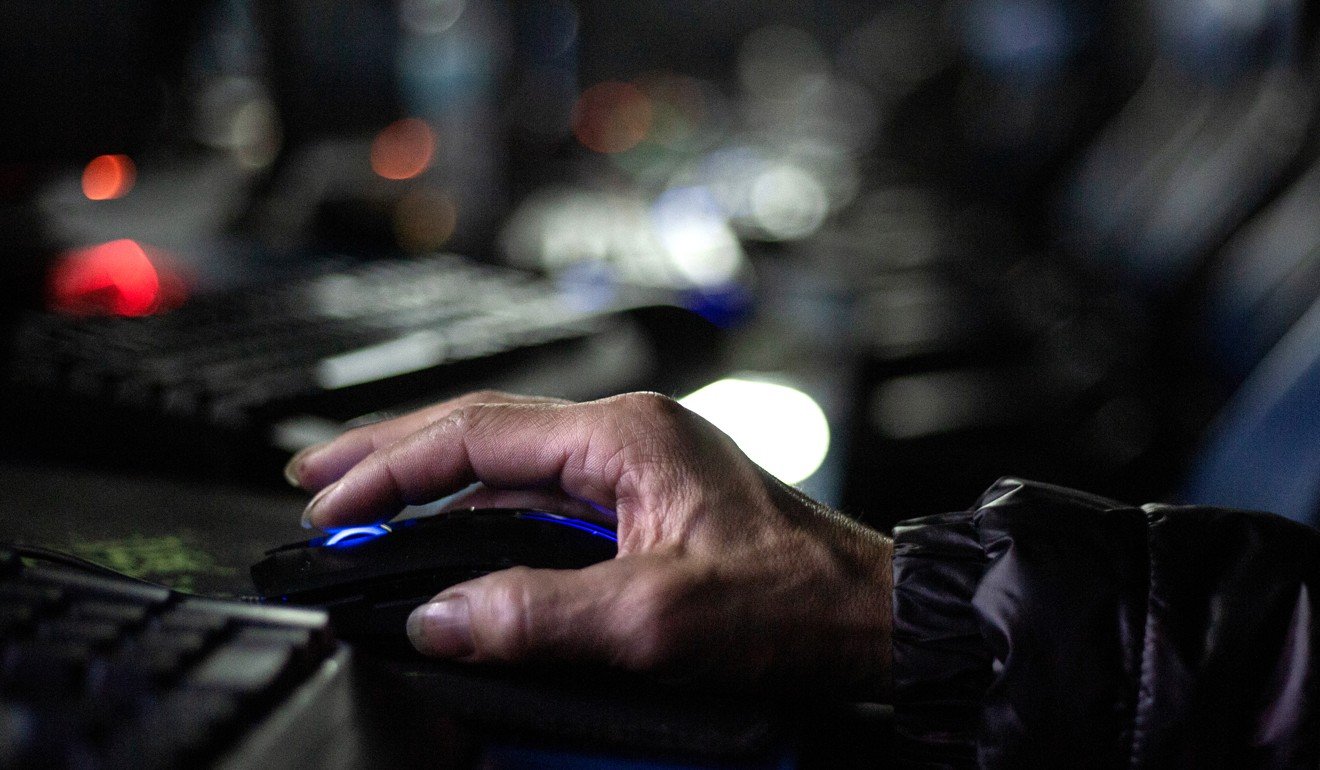

For the past seven years, dimly lit internet cafes in Sham Shui Po, Hong Kong’s poorest district, were homes to 50-year-old Hung (not his real name).

He spent every evening browsing the web at such establishments for movies and songs of the 80s, before hunkering down for the night. “These songs and films remind me of the better days of my youth. Without them, I’ve got nothing but painful memories,” he says.

As a young man in his 20s, Hung developed a gambling problem. At the time, he had lost his job as a bartender at a small karaoke club which closed down amid tough competition from rising chains.

Turning to Macau casinos to relieve stress, Hung rang up some HK$400,000 in debt. Although his family stepped in to help pay off the loans, his addiction and shame weighed heavily on him.

At 28, he left his mother and two elder siblings to start a life that would see him tough it out on bare streets to the city’s horrendously squalid subdivided flats, and finally, cybercafes. A month ago, he moved into a new hostel in Tai Kok Tsui, run by the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO), an NGO.

Hung had been one of an estimated 2,000 street sleepers in Hong Kong. In 2017 to 2018, officials pegged the number of registered street sleepers across the city at 1,127, but academics and NGOs believe the actual number is much higher.

“It’s hard to account for the so-called invisible homeless, who spend their nights at 24-hour establishments or old buildings. Considering how an increasing number of them are sleeping at places like internet cafes, I’d say the number is more than double”, says associate professor Wong Hung from Chinese University.

Last month, a food delivery man died of an apparent heart attack while staying overnight at a cybercafe in Sham Shui Po. His death cast light on the “invisible homeless” mentioned by Wong – especially on what the government and society should be doing to help them.

Perhaps most jarring of the statistics is that most of those who spend their nights at 24-hour establishments are employed, but sleep rough because they cannot afford to rent homes. According to official figures released last month, a record 1.37 million people in Hong Kong live below the poverty line on as little as HK$4,000 a month. Other street sleepers fall back into the homeless cycle after their transitional housing leases expire.

Experts argue that Hong Kong’s notorious property prices and rents, coupled with a lack of a comprehensive policy from authorities, are why the number of street sleepers has been rising over the years.

Ng Wai-tung, a SoCO social worker who helps people like Hung, says the lack of a centralised authority to look into the issue is to blame. He cites how public shelters are run by the Home Affairs Department, whereas outreach teams for the homeless are governed by the Social Welfare Department.

Ng says authorities should take cues from other cities such as New York, which has its own Department of Homeless Services.

“Compared with places like the US, the measures we have now are rudimentary.”

A price one can live with

Seven years ago, Hung was living in a subdivided flat when a friend proposed an alluring alternative: internet cafes.

The past few years have seen cybercafes gaining popularity over 24-hour McDonald’s outlets, another regular hang-out for street sleepers. To Hung, the cafes offered everything he needed – safety, shelter from the heat and cold, water supply and entertainment. The only thing lacking was a bed.

“The seats are usually quite large because they’re designed for gaming, but I still can’t stretch my legs out. I always had sore muscles and joints. I also suffered lower back pain.”

Still, Hung says a cybercafe guaranteed a better night’s sleep than other locations such as McDonald’s, where he reckons employees would wake him up “at least eight times a night”.

As for sleeping on the streets, Hung recalls what it was like: “Male passers-by have molested me, people have stolen from me, police have kicked me awake ... Every night, I had to sleep with one eye open. It was hard.”

According to government records, the number of registered street sleepers in Hong Kong jumped more than 40 per cent to 1,127 over the past five years.

A SoCO survey in March this year found that street sleepers who spend their nights at 24-hour fast food restaurants earn an average of almost HK$10,000 a month.

“When you don’t earn a lot but have to spend one third of your income on rent, it becomes a real burden,” Ng from SoCO says.

Hung says of his days in subdivided housing: “I was paying HK$1,500 a month for a room that was ridden with bed bugs and rats, and had no window or air conditioning.”

“Staying at an air-conditioned internet cafe for less than HK$40 a night sounded like a much better deal.”

Staying at an air-conditioned internet cafe for less than HK$40 a night sounded like a much better deal

Although he now earns around HK$15,000 a month as a delivery worker, Hung still feels he cannot afford HK$4,000 to HK$5,000 for a subdivided flat in Sham Shui Po, the city’s poorest district. A typical unit measures less than 100 sq ft.

“I can’t spend a third of my income on rent. I still need money for food, drinks, transport, cigarettes, the laundromat, phone bills ... Sure, I can scrimp and save for a tiny flat, but it’s not worth it.”

Hong Kong has fewer than 600 bed spaces for the homeless. About 40 per cent are government-subsidised, and can be occupied for a maximum of six months. They are provided by a hospital and several NGOs for free, or for up to around HK$1,800 a month.

The remaining non-subsidised bed spaces are available to street sleepers for up to only three months.

“Before 1997, the assumption was that residents would be able to find a decent and an affordable place to rent after three to six months. That isn’t the case any more,” Ng says.

“Social workers need to invest time and effort to help street sleepers find accommodation and work. But it’s hard to get someone back on their feet within just six months, so it becomes a vicious cycle of helping the homeless, and then having them return to the streets,” he adds.

But it’s hard to get someone back on their feet within just six months

Ng says the number of times street sleepers fall back through the cracks has increased from an average of 2.8 times in 2013, to 4.4 times in 2017.

For Hung, that number is six. When asked if he had considered applying for public housing, Hung reveals he is still a registered occupant of the flat in which his family resides. But he is too ashamed of his gambling past to move back or even face family members to settle paperwork that would allow him to reassign his name and apply for another flat.

And, even if he did so, Hung would likely have to wait at least more than five years to move in. Latest official figures in August on the waiting time for public housing in Hong Kong are the longest in 18 years.

“I brought shame and distress to my family, and now I have to live with the consequences, even if it means spending every night at a cybercafe. At least time passes more quickly when you’re on the computer.”

The last cafe standing

Since internet cafe owner Cheng Yiu-chung first set up shop in a factory building in Shek Tong Tsui a decade ago, rent has more than doubled, but his customers have not.

The musty 900 sq ft place reeks of stale fast food and sweat. White fluorescent lamps cast a pasty glow on the grimy faces of customers – mostly men – and illuminate polystyrene takeaway meal boxes by some keyboards.

In its early days, students and young adults queued by the dozen outside the two-storey unit. Now, on a good day, only about two-thirds of 90 desktops would be occupied.

Cheng, 52, relies partly on regulars to keep his business going, including young adult gamers, and customers seeking temporary refuge.

One such client is a 30-year-old man who goes only by “Fung”. Unlike Hung, he has a proper home, but says he spends around three nights a week at Cheng’s cafe to avoid his mother’s persistent nagging at home.

A delivery worker who earns about HK$11,000 a month, Fung says his income is not sufficient for him to move away from a turbulent life at home.

“Even if I manage to find a better job, it still wouldn’t be enough for rent.”

Others who frequent Cheng’s internet cafe are people like Hung, who stay overnight at his business. He calls them his “VIPs”.

“I feel for them. They’re like me, the working poor,” Cheng says. He laments that if his rent is raised by another HK$10,000 a month to HK$20,000, he would lose a chunk of his income.

I feel for them. They’re like me, the working poor

Cheng says he began seeing more “VIPs” three years ago, and now provides a place to sleep for eight to 10 of them nightly for just HK$55 each. He is willing to let street sleepers spend the night at his cafe as long as they do not disturb other customers.

“It’s a fair game. They pay me, and I provide them with seats,” he says.

In reality, Cheng offers more: he has fixed an electric fan over a seat for Calvin, a “VIP” who typically spends 10 nights a row at the place because he “lives too far from his workplace”, and reserved a permanent desktop for a non-Chinese customer who refused to be interviewed.

As for Hung, he had to move from one internet cafe to another in Sham Shui Po and Shek Kip Mei.

“They just kept shutting down,” he says of the five cybercafes he had frequented over the years.

“But I’m not too worried about the future of the business. There are so many of us around to keep demand up.”

Cheng, however, is less optimistic. He claims his internet cafe is the only one left in the Wan Chai and Sai Wan area. The former trading company worker says he will just have to learn to adapt when he has “run out of money to lose”.

“Before I started this business, I worked at a trading company – and then the factories moved to mainland China. I don’t know what’s next, but I really don’t have much hope.”

Hung now pays about HK$1,800 a month for one of 24 bed spaces at SoCO’s social housing project, where he expects to stay for the next three years.

Chinese University’s Wong says one way the government can tackle homelessness is by helping NGOs shoulder the burden of managing social housing.

“It’s not enough for landlords to lease their properties to NGOs at affordable prices. The government should also give more support for NGOs to renovate and manage the properties, and maintain order at the hostels,” he says.

The government should consider implementing a housing-first policy that provides accommodation to street sleepers, no questions asked

Ng from SoCO says his group hopes the government would eventually extend the length of stay at all hostels for street sleepers to more than three years, to provide them with a more realistic time frame to get their lives together, and to build an additional 1,000, or even 2,000 bed spaces.

“The government should consider implementing a housing-first policy that provides accommodation to street sleepers, no questions asked,” he says.

“Right now, some providers in Hong Kong might turn away those who have problems, like drug addiction or psychological issues. With a housing-first policy, these people would be given a place to sleep first, and then be treated for their conditions.”

Meanwhile, Wong suggests the government adopt a multifaceted approach – from regulating rent to improving social hygiene.

“Bed bugs are a big reason why many street sleepers would rather sleep rough than rent subdivided flats. The government might think bed bugs are a household problem, but when bed bugs are driving people out onto the streets, it becomes a social issue.”

Like Ng, Wong is also calling on authorities to provide cheaper but liveable housing in urban areas such as Yau Ma Tei, where work is more readily available.

In the meantime, Hung lies on his new bed, legs outstretched. All that is left to do now, he says, is live for the moment.