How to beat adversity: from losing both arms as a child to pro-athlete and top academic with Jesse Yang Mengheng

- Jesse Yang Mengheng loses both arms after being electrocuted – the first of many setbacks as ‘defeats’ outweigh ‘triumphs’ for former Paralympic hopeful

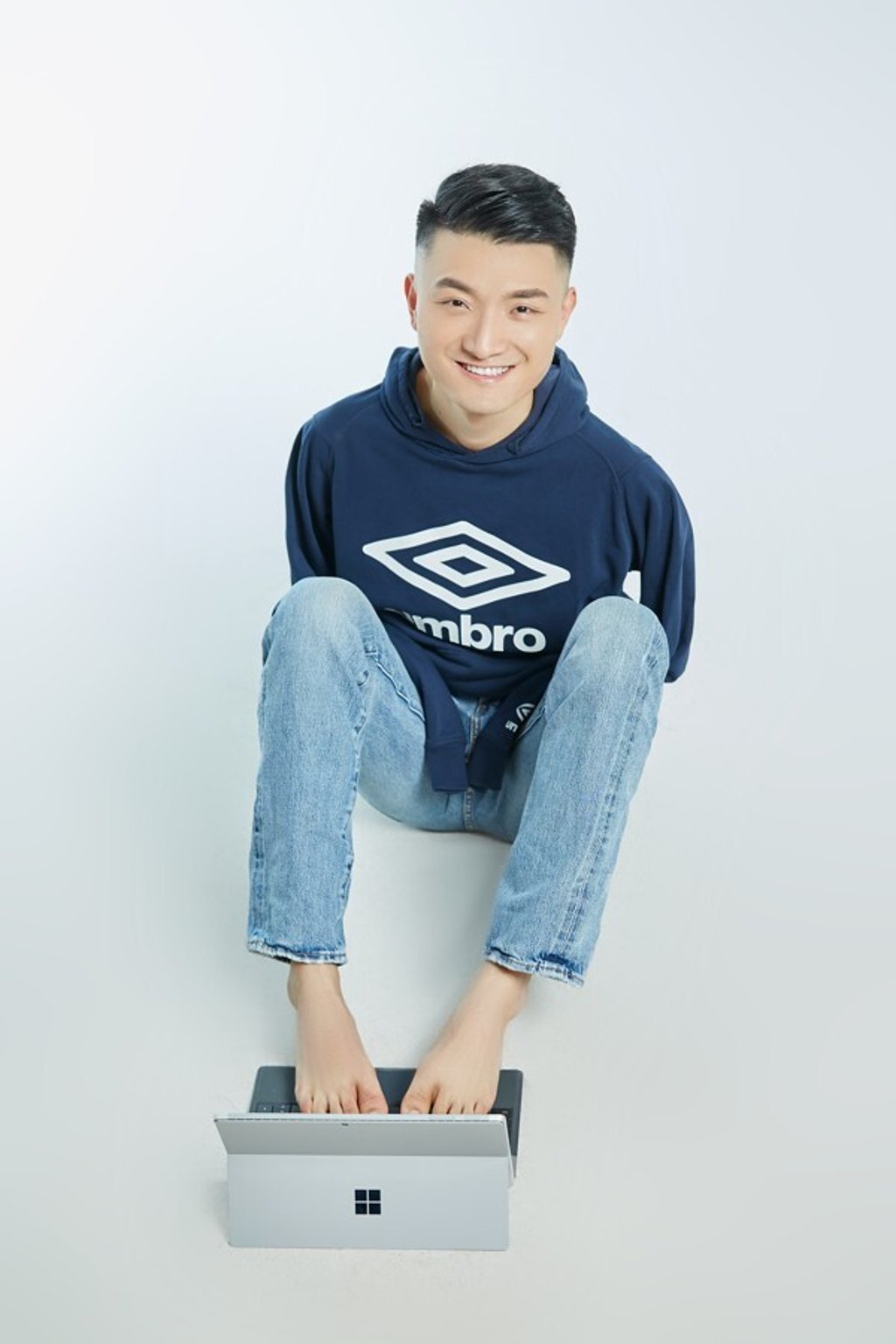

Jesse Yang Mengheng lost both arms at the shoulders as a child but that did not stop him pursuing a life in sport. Endowed with athletic talent, he seemed destined for the highest stage, but injuries and bad luck ended his professional sporting career.

Yang then excelled academically, graduating from an elite university and earning an MA from Cambridge. Now 30, he is also an inspirational motivational speaker and educator.

“Yi bai tu di” is a Chinese saying that means a defeat that leaves you flat on the ground. Yang tells his life story in terms of such defeats – four, along with two triumphs.

Yang was born near Kunming in Yunnan province, in a family of schoolteachers. At the age of six he climbed an electrical transformer and was electrocuted: “When I woke up several hours later, my arms were burnt. Doctors had to amputate them to save my life.”

He learned to write and eat using his feet. “It took me about three months. It is easy to learn at a young age.”

Some kids at school “mocked and bullied” him because, using his feet, he wrote and ate much slower than they could.