Fingerless tennis pro swaps tour life for teaching Hong Kong youngsters and could not be happier

- Born without fingers on his left hand, Brett Hillier taught himself to excel at junior level tennis in Australia

- He now passes on lessons learned on and off the court to his students at Discovery Bay Recreational Club

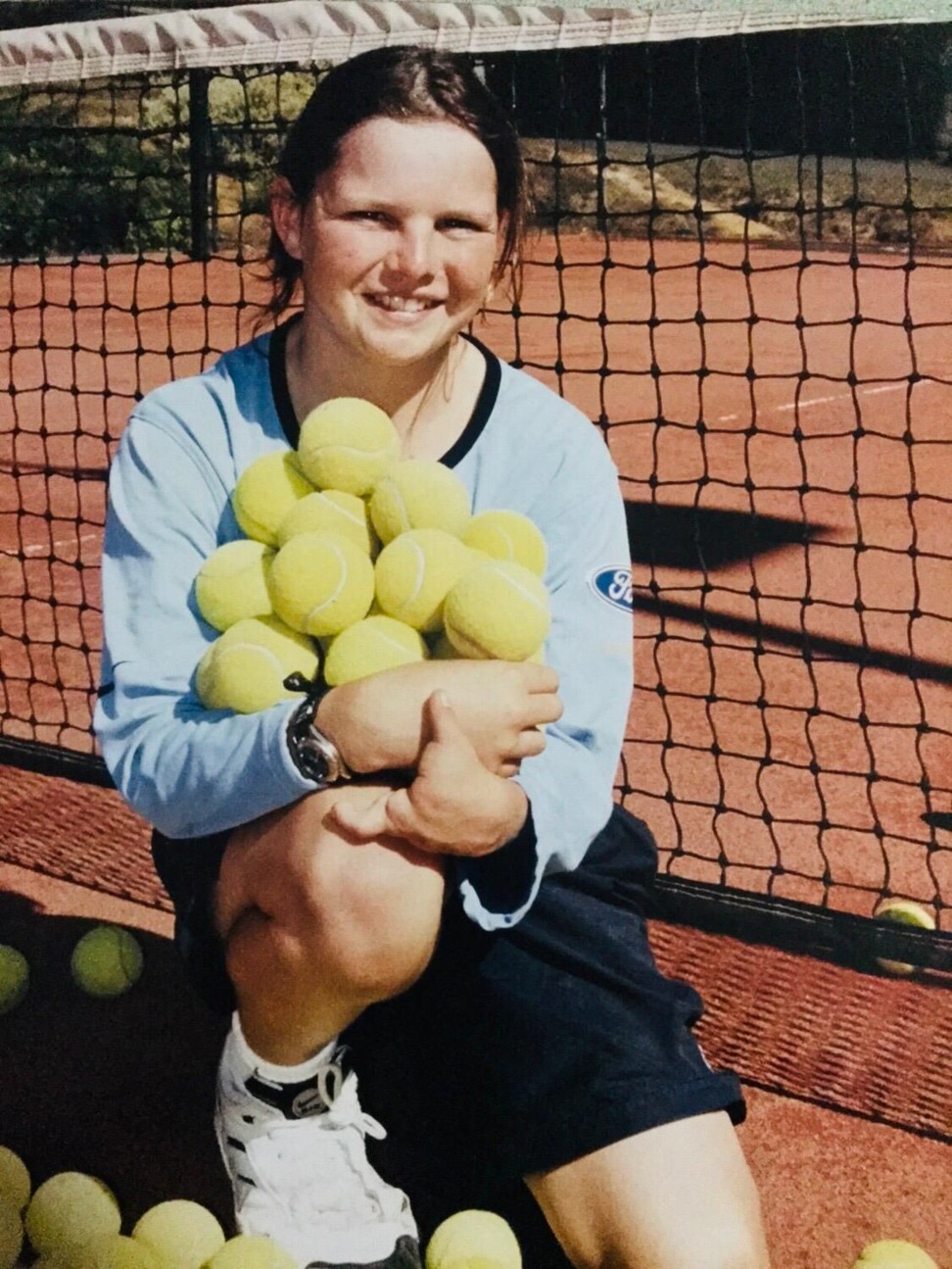

Australian Brett Hillier, who works at Discovery Bay Recreational Club in Hong Kong, isn’t your average tennis coach. He was born without fingers on his left hand – a blood clot had cut short the development of his wrist, leaving a stump with a reduced thumb.

When Hillier was five, doctors transplanted a toe onto the stump in a pioneering operation to enable him to grab objects, but the procedure did not fully work.

“It left me with a competitive outlook. I never used it as an excuse,” Hillier says. “As a kid I wanted to be normal, which in Australia means doing sports. I was pretty quick and my hand-to-eye coordination was good.”

Athleticism and inner drive enabled Hillier to excel at two sports at once at junior level, Australian rules football and tennis.

“In football my hand affected me a lot … I could only tackle with one hand… but I found ways to get around that,” he said.

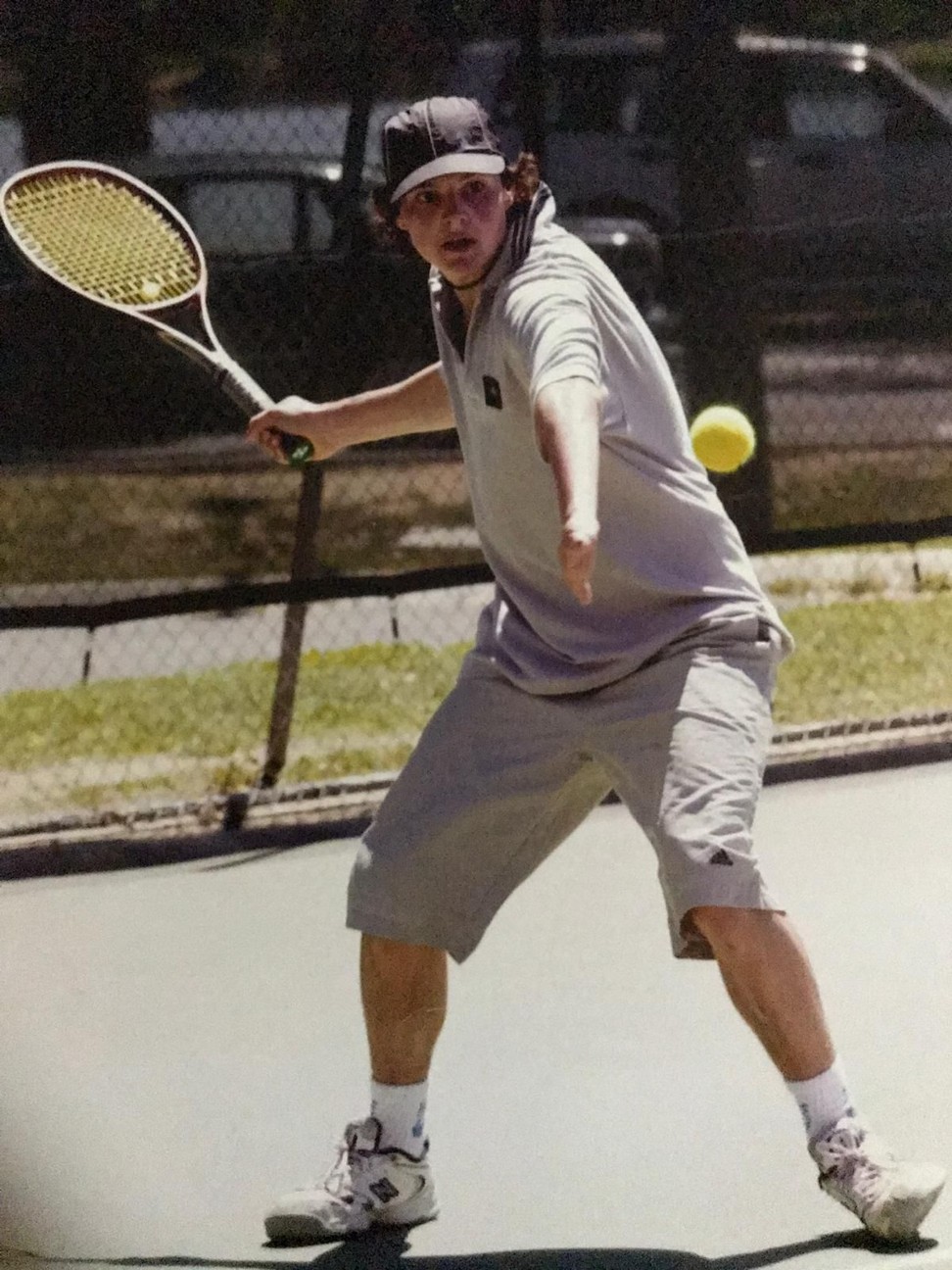

He was confident on a tennis court, though. “My opponents played normally, my hand was never spoken about,” Hillier said, but off the court he was nervous and would always hide his hand in his pocket.

At the age of 12, Hillier decided to focus solely on tennis – his hero was fellow Australian Pat Rafter. The long-term goal was to turn professional, but first Hillier had to solve the problem of learning techniques which required the use of his left hand.

He constructed his own backhand, and perfected it overtwo years. “I learnt how to insert my stump into the V in the neck of the racket [for support],” Hillier said.

Tossing the ball on his serve took him longer to master. Hillier had to learn how to balance the ball on the stump and then launch it upwards, perfectly straight.

“I would take a backpack filled with balls and practise for hours after my normal training,” Hillier says. “An umpire once said to me that my ball toss was the straightest and the most consistent he had seen.”

At 18, Hillier was ranked high enough for an attempt at cracking the professional game. He started on the Futures Tour, the third tier of professional tennis, playing in Thailand, Argentina, Australia, Spain and France.

It was all self-funded. “There is a very big divide in tennis. If you are ranked in top 80 in the world, you are making a good living, but below that … I worked in a bar, I picked lemons, I coached,” he says. “My parents met me half way financially. Travelling, it was pasta out of the microwave, 15-bed dorms.”

It was a time of instability, pressure and stress. After a year, at 19, Hillier called it a day.

“I was one of the fittest players because I was a much harder worker than everyone else, but I struggled to put it all together mentally on court.” Hillier says.

“I burnt myself out working, travelling and playing tournaments. My parents could not support me anymore either. It was not exactly depression, but, ‘Oh, I ‘m not good enough’.”

He then coached children for a year at an elite academy in Spain, where he picked up the language but also feelings of resentment.

“Nothing is ever good enough for a Spanish coach,” he says. “I knew this was not my style, but I did not yet know what my style was. You can teach tennis very easily – simple repetition will do it. But I felt that something was missing.”

Hillier went home to Australia to try to find an answer. He did odd jobs and coached, eventually as part of the National Academies, thinking a lot and educating himself on psychology, neural plasticity and cognitive science.

“Your tennis is a just a reflection of how you are in life,” he says. “The goal is to turn the students into self-aware, confident, happy human beings, and only then they become real tennis players. Better tennis becomes a by-product of happier, more aware existence.”

Hillier’s own tennis has responded to this cognitive shift, as he’s rolled back the years.

“I’m now more comfortable with myself as a human being. And I’m now a better tennis player as a calm, composed 30-year-old, as opposed to that anxious, stressed 18-year old.”

He even feels he can be competitive as a player again, more than 10 years after quitting the professional tour, and says he’s thought multiple times about making a comeback.

“But now I want to do new things, like distance running – I ran across Australia – and I have just started rock climbing. I want to experience what else the word has to offer, milk life for all it’s worth, and do it with good people,” Hillier says.