Opinion | West Asian nations cannot wish away their neighbours – they must take responsibility for making peace

- Leaders of regional states trapped in a cycle of conflict must step up to the plate to stop another march to war over Iran

- If they cannot, the result will only be a continuation of the perpetual instability, on-the-ground misery and poor prospects for collective success that have plagued the region for decades

But by the dint of changing tides in history, both nations have also experienced national humiliation at the hands and encroachment of Western imperialism, and pride themselves on turning the page, restoring their national dignity in the face of foreign interference and meddling, and reassuming their rightful place in the community of nations on their own, independent, terms.

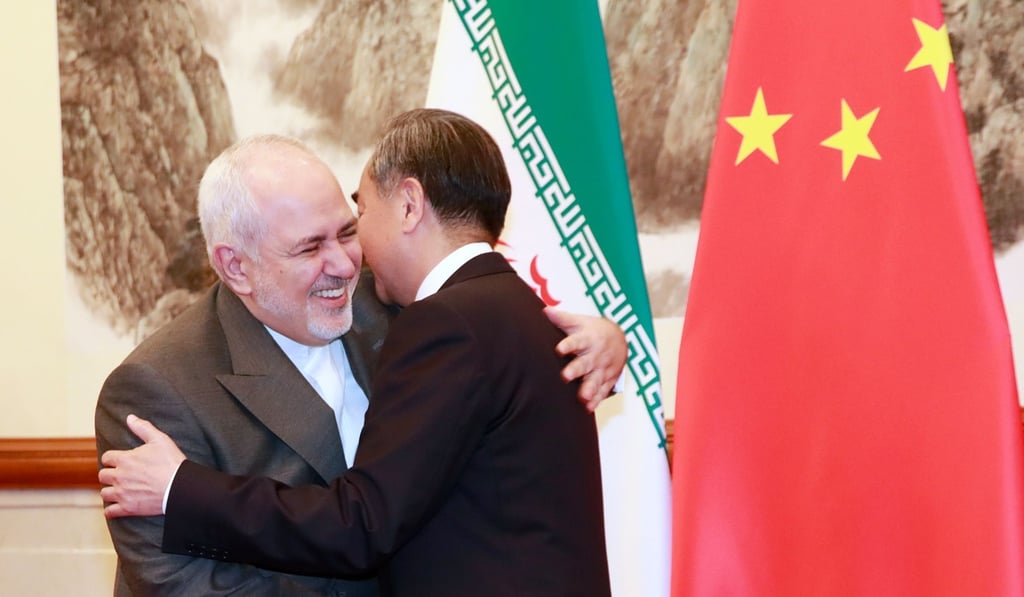

These common historical memories have not only influenced Chinese and Iranian strategic cultures and world views, but also, in many ways, define Sino-Iranian relations in the modern age. The contemporary “comprehensive strategic partnership” between Tehran and Beijing is rooted in this background but also a pragmatic and cold calculus that considers close and reinforced relations as being advantageous to both countries’ national interests, writ large.

This is to say nothing of the obvious relations and growing investments of China in the wider region, including with Saudi Arabia and other states in West Asia, commonly known as the Middle East.