Sauna at the office: How co-working spaces are luring China’s young innovators

Fuelled by Beijing’s calls for an economy based on innovation, shared office spaces with Chinese characteristics are taking off

Just five years ago, freelancers and entrepreneurs in search of co-working spaces in China were relegated to searching for cafes with readily available outlets to plug into, or renting small apartments with like-minded souls in the cheapest places they could find. There was little sense of community for scattered innovators.

WeWork, valued at around US$18 billion and with a presence in more than 140 locations in 15 countries, has turned its attention to China, opening two co-working spaces in Beijing in May, after two openings in Shanghai. It hopes to open a co-working space in Shenzhen as early as 2018, a WeWork employee said during a tour of the new Beijing space on Guanghua Lu.

WeWork’s biggest Chinese rival, UrWork, recently announced it had raised US$58 million to invest in new spaces, and now has dozens of locations in 20 cities and is looking to expand in Shenzhen and elsewhere.

Co-working office providers flock to Shanghai, Beijing

These two major players are a bit tight-lipped about publicity, a sign of how competitive the co-working market has become in China. WeWork, UrWork and other co-working operations in China don’t like to be called “co-working spaces”. They prefer the term “communities”.

“Community is the key,” Michael Michelini, founder of GlobalFromAsia, a Shenzhen-based start-up that educates Western companies about e-commerce opportunities in China. “The real successful ones build the community before they launch the space.”

Michelini knows this the hard way. In 2012, when there were really no such spaces in Shenzhen, he and a handful of others tried to launch their own space, failing in about six months.

“They say that pioneers often come back with arrows in their backs,” Michelini said. “We were definitely early.”

In February, another attempt at a co-working space called Shenzhen Basement closed down. Yang Binglong, head of the company, said that the company had spent about US$150,000 to launch, but bled funds quickly amid tough competition.

The successes now outnumber the failures, however. The recent WeWork and UrWork moves show co-working is taking off at the right time in China.

“Rents and cost of living will continue to increase, putting pressure on people to find places to work,” Michelini said.

Shenzhen co-working brand SimplyWork has carved itself a niche with six locations, mostly centred on the Hi-Tech Park area in Nanshan district.

Five of Hong Kong’s best co-working spaces reviewed - free beer if you’re lucky

SimplyWork also appears to have found a balance between renting offices to small dot.com and hardware tech start-ups, and individual freelancers who use a space for a monthly fee of about US$100.

“We want to build a co-working brand that centres around community,” Shun Lei, branding manager at SimplyWork, said. “I’m not saying that bigger brands don’t care about this, but from my point of view, I think if you want to build a good community, you need to put a lot of effort into it.”

In many ways that balance is similar to WeWork, which has a good mix of start-ups and individuals drawn in by a sense of excitement, community, activities and interaction. But while WeWork has a more international clientele, SimplyWork is still quite local.

“They [bigger players] target teams and freelancers that have connections with international markets, while our members are more locally based,” said Shun. “I won’t worry much about the competition though, as co-working is just beginning in China, one brand can’t take care of the market on its own.”

At the other end of the spectrum, UrWork, WeDo, and CoWork locations in Shenzhen have a limited number of available spaces for individual freelancers, though most are jam-packed with start-ups – usually at least around 90 per cent capacity – giving the sense that China still has some way to go in growing a gig economy.

“I think as our younger generation joins the workforce, we’ll see more and more freelancers in China,” Shun said. “Because compared to other generations in China, they want to work happily, which means they want to do something they love in a nice environment, meet interesting people and collaborate.”

Extras including gyms on site, meditation rooms and even saunas add to the attraction and hipster feel of some of these locations, appealing to a younger generation that does not adhere to the iron-rice bowl mentality of sticking to danwei, or work units, for life.

Most spaces also have weekly group activities and visiting speakers to add to the sense of community.

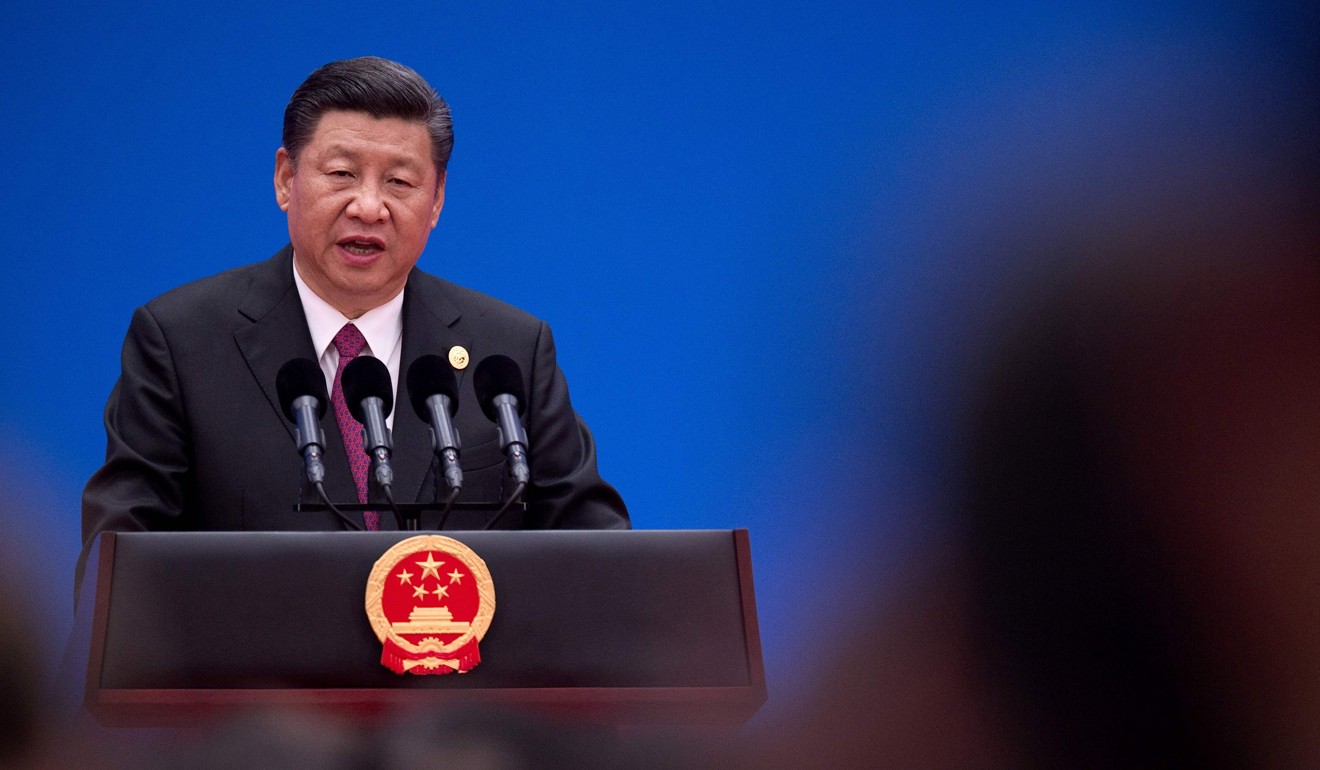

“I think the government is concerned about that shift from blue collar to innovation,” Michelini said. “The government is indirectly or directly funding [the drive to innovation], and second, the market is ready for [co-working spaces].”

The constant ringing of the innovation bell by the government has also made it easier for young people to tell their parents they are joining a start-up, which increases the viability of co-working spaces in China.

“They know it now. They read about it and hear it on the news, so it is a bit easier for [younger people] to work in these spaces now,” Michelini said. ■