Fighting cancer in Singapore, eating plastic in Indonesia: is Southeast Asia the next Silicon Valley?

Filing taxes using blockchain in Indonesia. Growing better crops in Vietnam with artificial intelligence. Sending rockets into space in Singapore. Southeast Asia is quietly emerging as a breeding ground for new technology

Charles Guinot’s journey to building a multimillion-dollar business started ordinarily enough.

He was at a conference in China in 2015 when he first had an idea on how to use blockchain technology to solve his “painful” problem of filing taxes in Indonesia.

To turn this idea into reality, the then 30-year-old robotics engineer from France decided to reprogram himself to become a blockchain developer because such developers were practically unheard of at the time. His intensive self-study paid off.

How bitcoin and cryptocurrencies went from Wall Street to the high streets of Southeast Asia

Now, Guinot’s company, Jakarta-based OnlinePajak, is one of the fastest-growing start-ups in Indonesia, handling tax transactions worth US$3 billion last year. He expects the figure to reach US$7 billion in 2018, or roughly 10 per cent of the country’s total tax revenues.

OnlinePajak allows users to record their tax deposits and transactions with a few clicks instead of filing reams of paperwork. Since the platform is built on blockchain, all the information is secure against fraud.

Essentially, a blockchain is a digital ledger – a continuously growing list of records, called blocks, that are designed to be resistant to modification. Blockchains, which gained notoriety for their use as the foundation for cryptocurrency, enable information to be shared in peer-to-peer networks, and because data in any given block cannot be altered without altering all subsequent blocks, they can withstand fraud in highly corrupted environments.

Singapore’s university challenge: to value skills as much as degrees

The four-year-old start-up has helped 800,000 corporate and individual users iron out their tax reporting. Its initial platform is free, but some additional features, such as payroll tax filing, requires users to pay a fee. The business model is so appealing that venture capital firms, including Silicon Valley’s largest venture firm Sequoia Capital, have poured millions of dollars into the company. Indonesia’s tax agency has also appointed OnlinePajak to be its official e-filing and e-billing partner. The company plans to help Indonesia track its tax expenditure using blockchain.

WATCH: Ant Financial targets Philippines with blockchain-based money transfers

Across Southeast Asia, experiments are underway. Last month, the Philippines rolled out a red carpet for the country’s first-ever blockchain-based work space that focuses on financial technology, tieing the knot between the 21st century technology and old-school banking services.

Blockchain Space, the office operator, has launched similar projects in Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur.

It also plans to expand into Thailand and Vietnam later this year.

Forget China: Hong Kong, Singapore are new kids on the blockchain

OnlinePajak and many other blockchain start-ups are part of a broader movement in the region. While Southeast Asia has yet to establish itself as a global tech hub, it has quietly emerged as a breeding ground for new technology.

If US tech companies are indeed cut off, Chinese investment will flow elsewhere. China’s largest hi-tech companies have already made forays into the region, with Alibaba Group, the owner of the South China Morning Post, buying the Southeast Asian e-commerce firm Lazada Group and signing cooperation deals with Malaysia and Thailand.

Tencent Holdings, the gaming-and-social media giant, has invested in Singapore-based Sea, which operates the Shopee e-commerce site and Garena gaming and esports platform. JD.com, the Chinese e-commerce firm, led an investment round into Thai online fashion brand Pomelo last year, while the region’s two biggest internet platform start-ups, Singapore’s Grab and Indonesia’s Go-Jek, count Chinese tech unicorns Didi Chuxing and Meituan Dianping as investors, respectively.

To see why Trump’s tariffs have hit a Chinese nerve, read history

Southeast Asia “is becoming a proxy war for large Chinese internet companies like Tencent, Alibaba and we think going forward this will increase”, says Hian Goh, who founded Openspace Ventures in 2014 and has invested in start-ups such as Go-Jek, Halodoc, Redmart and Chope. “Already, we see Go-Jek, our portfolio company, receive investments from JD.com as well as Meituan, and JD has done a joint venture with Central Group in Thailand. We think a lot of the capital funding could come from these strategic sources as well as venture capital.”

Innovation can be seen everywhere in the region. In Indonesia, a data analysis company powered by artificial intelligence (AI), Dattabot, has created a blockchain-based data exchange platform called HARA to help small farmers produce bigger and more efficient crop yields.

In Vietnam, the start-up Sero has bet on AI to identify crop diseases and send farmers treatments for the diseases. Sero claims its virtual doctor is capable of identifying 20 diseases with an accuracy of 70 to 90 per cent.

The region’s technology exploration is not limited to blockchain and AI. Companies have popped up that specialise in the internet of things, essentially a practice that connects devices via the internet to improve performance and add features, such as when your phone controls the lights in your home.

In the Philippines, where 103 million people are scattered across 7,000 islands, this might not only save money but save lives. IoTs Philippines Inc has developed smart body sensors for Filipinos living far away from hospitals. The device allows doctors to remotely collect real-time data from patients and monitor their health.

The bitcoin party is over. The blockchain party has only just begun

“Southeast Asia is starting to see an increased number of companies in the advanced or deep technology space,” says Vishal Harnal, a partner at 500 Startups, a global venture fund in Singapore.

As Harnal explains, the recent success of home-grown unicorns such as Grab and Go-Jek, as well as internet platform Sea, has lured many researchers into the entrepreneurial world, where they can translate their expertise in advanced science to start-ups with advanced technologies.

Meanwhile, governments have opened their coffers to help commercialise laboratory findings and venture capitalists have also expressed a greater desire for Made-in-Asia technologies.

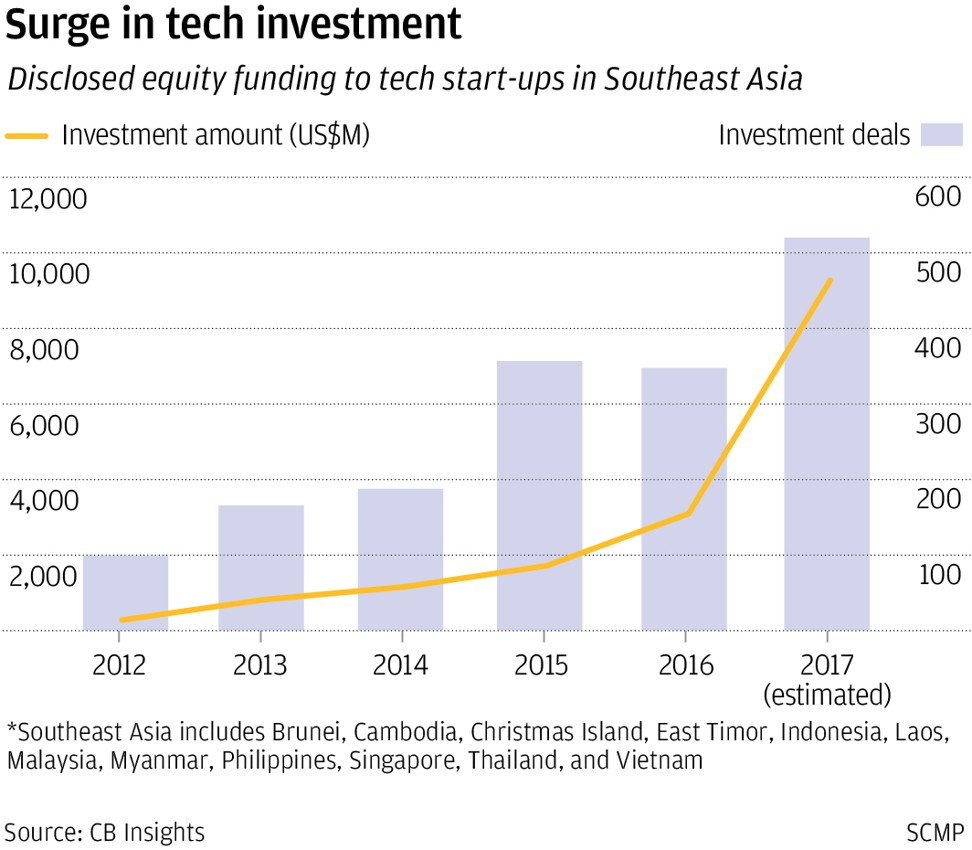

Investors have been quick to pour money into ride-hailing firms, e-commerce and travel portals, Harnal says.

“So what’s next? I think a lot of opportunities are in the advanced or deep tech space.”

How Indonesian unicorn Go-Jek went from 20 bikes to US$2.5 billion and an e-money revolution

That’s particularly true in Singapore, which has transformed itself into a launch pad for hi-tech companies. A 2016 survey by the National University of Singapore found nearly half of 530 start-ups there own the rights to at least one intellectual property. Last year, Singapore was ranked the seventh most innovative country in the world by Cornell University, INSEAD and the World Intellectual Property Organisation. Singapore is also fast becoming a space technology hub, bolstering start-ups that experiment in everything from launching backpack-size satellites to using lasers in space communications.

Life-saving medicines may also soon be discovered in the Lion City. ASLAN Pharmaceuticals, a Singaporean biotechnology company, for one, has four cancer-fighting products in the pipeline. The start-up has made its way to the Nasdaq Stock Exchange eight years after its debut.

Goh, of Openspace Ventures, says other Southeast Asian nations have advanced, too. “You can see semiconductor processes coming out of Malaysia, food tech out of Thailand, and a lot of algorithm and software-based AI out of Vietnam. So every country seems to have its own flavour.”

But whether the region could be counted as a breeding ground for cutting-edge technologies depends on how those technologies are defined, says Kay Mok Ku, a partner at Asia-focused investment firm Gobi Partners. Given the massive capital and market scale required to nurture hi-tech companies, “the fundamental breakthrough will be from the West and maybe China”, he says.

US$1 billion down, why is Japan still in love with bitcoin?

Governments in Southeast Asia beg to differ. In a conference last month in Jakarta, Triawan Munaf, head of Indonesia Creative Economy Agency, a governmental arm established to boost entrepreneurship, said he wanted the country to master blockchain, a technology that many say will change the world in the same way the internet has done over the past 20 years.

“Indonesia could be an innovator in blockchain application, not just a user,” Munaf said. “Blockchain could create a US$400 billion economy in the next four years across the world, we don’t want to be left behind.”

But Indonesia’s pursuit of blockchain technology is not just for pride; it is also about solving a persistent challenge facing the region. Southeast Asia has a reputation for a lack of transparency, and is marred by scandals ranging from a recent seizing of fraudulent passports in Thailand to a 2007 medicine crisis in Laos in which half of antimalarial drugs tested turned out to be counterfeit. Experts say blockchain, thanks to its traceable character, could serve as a silver bullet and help restore trust in institutions.

James Song, the founder of ExsulCoin in Myanmar, has been testing the theory.

Why is South Korea suddenly terrified of bitcoin?

His start-up has embraced blockchain to help Rohingya refugees. It works this way: ExsulCoin runs an online platform where refugees can list a service or take a vocational course. Their performances are then rated by customers or teachers. As the platform is powered by blockchain, the ratings cannot be manipulated by people using multiple usernames.

It is too early to know whether such an attempt would succeed – so far, only 20 Rohingya women have taken part in a bracelet making course through a pilot programme – but Song says blockchain has already given his company a boost.

In April, the one-year-old start-up raised US$4 million through an initial coin offering (ICO), a digital token-based fundraising method built upon blockchain. If the ICO were not in place, “it would have been difficult to raise money for the business because it sounds like a non-profit endeavour”, Song says.

Not everyone welcomes the brave new world of blockchain.

“I think a lot of Southeast Asian companies doing cryptocurrencies are scammers because they don’t really need the blockchain technology for any of those things they are doing,” says Edith Yeung, a partner at 500 Startups. The driving force behind the boom is an expectation that “the concept of tokenisation would help them raise money”, Yeung says, referring to a rising popularity of creating digital tokens in exchange for fiat currencies from individual investors. Such exchange requires no more than a business proposal and people with little financial know-how are often an easy mark.

A prime example is Modern Tech, a Vietnamese start-up which raised US$660 million claiming it was a cryptocurrency company. It turned out to be a Ponzi scheme.

You have not arrived: why Google Maps is a lost cause for Indonesian drivers

Some market observers worry the solutions to problems the new technologies offer might become the causes of other problems. With AI gathering steam and large amounts of data flowing to empower machine learning, how to protect privacy in a region where the use of personal information is loosely regulated has become a pressing question.

There is also a concern that AI and other new technologies rely on robust communications networks, yet most Southeast Asian countries are still in dire need of infrastructure upgrades.

But the biggest barrier Southeast Asia faces in building its tech muscle is a lack of talent, says Tiang Lim Foo, a partner at Singapore-based venture capital firm Seedplus. It is an uphill struggle to find entrepreneurs who are able to both produce technologies that can be revolutionary and also run a business, Tiang says.

WATCH: How technology is improving education in rural China

Besides that, investors specialising in cultivating hi-tech start-ups are still few and far between – although the possibility of more Chinese money could change that.

Industry players say a lack of willingness to experiment with new technology, which typically requires years of research, could impede the development of deep tech in the region.

“We are going very slow because we need an insane amount of education. Blockchain is a technology that honestly is quite new. Governments, anywhere in the world … they don’t want to change too much,” Guinot of OnlinePajak says. “So we need to go step by step to make sure they always understand the full implication of what we are building. This takes a lot of time.” ■

With additional reporting by Chua Kong Ho and Zen Soo