How to save Hong Kong maids from loan sharks

Social enterprises and non-profit organisations are using apps and other tools to cut costs and offer cheaper loans to foreign domestic workers across Asia, who are often excluded from traditional banking

But quickly, her life spiralled out of control. “I was worried all the time, could not sleep, could not support my family back home and had to be very careful so my employer did not know about the problems I was going through,” she says.

Debt collectors would call her twice a day and their tone became increasingly threatening.

“I really did not know what to do.”

The problem often gets compounded when workers seek additional loans to send their children to school, build a house, set up small businesses or deal with unexpected emergencies.

How Hong Kong failed Madagascar’s domestic helpers

Against this backdrop, social enterprises and non-profit organisations across Asia are combining technology, ethics and education to offer financial services to a previously excluded group of people. These services may take thousands of migrant workers, like Ana, out of debt traps – a situation that can make them vulnerable to forced labour and exploitation.

Jared King, a Canadian entrepreneur who had a consultancy company that worked with banks and other industries in Asia, was looking for an altruistic business opportunity when Joy Tadios-Arenas – an expert on migration and former assistant professor at City University of Hong Kong – told him about the lack of ethical options for domestic workers who need loans.

The pair hope their company can be a game changer in an industry plagued by unscrupulous practices and save domestic workers HK$100 million over the next five to seven years by reducing interest rates. Since they launched the firm – without a marketing campaign – demand has surpassed their expectations, they said, without revealing figures. “In terms of rates, we are at the lowest in the market [for domestic workers] … The amount per month is 1.7 per cent … We are starting here and then we want to drop it and drop it, as low as possible,” King says.

Widodo: Halting domestic worker exodus will take at least five years

Other licensed lenders usually charge somewhere between 2 and 2.5 per cent. For illegal lenders the typical rate is 10 per cent per month, with some going even beyond 30 per cent. The city’s highest legal interest rate is 60 per cent a year.

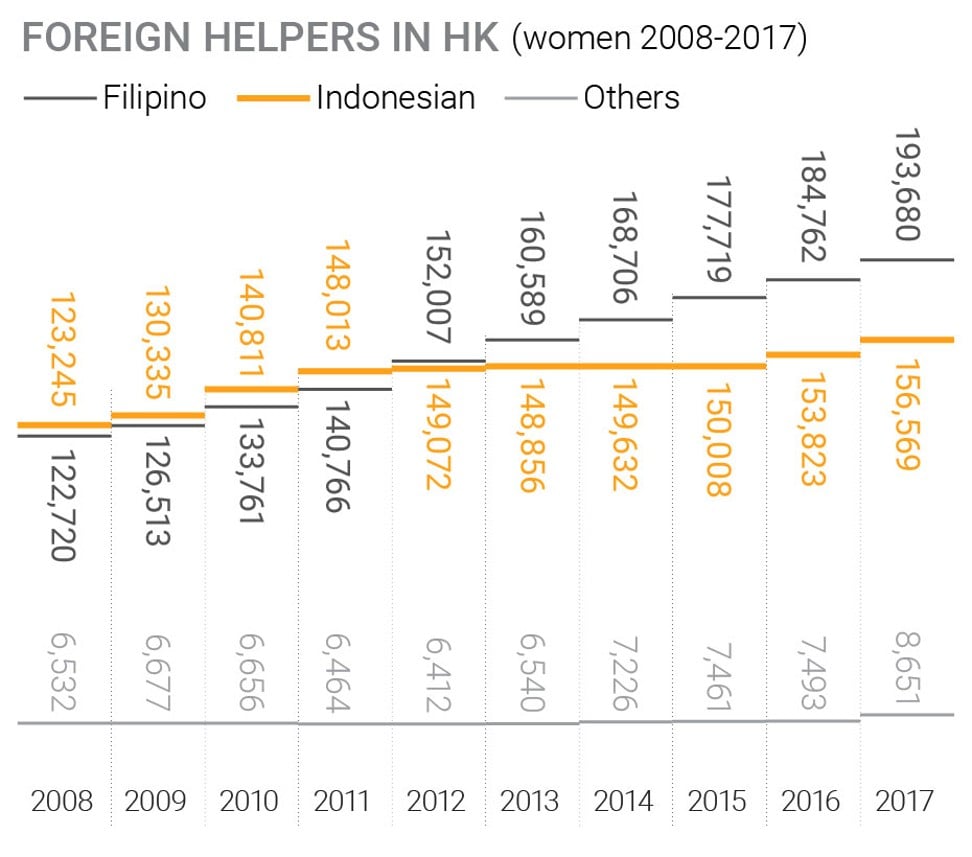

Domestic workers are not able to seek loans from banks in Hong Kong, forcing them to turn to licensed lending companies or even loan sharks and friends.

“I was so depressed because I knew I had a big financial problem.”

She had taken a loan to put her two children though university – which can cost up to US$6,000 per year in the Philippines – and then she had to pay-off a friend’s loan because she had agreed to serve as a guarantor. “If it was just my own loan, I could have dealt with it. But then my salary was not enough for two loans and I had to take money from loan sharks,” Ana recalls.

What turns a Hong Kong maid towards Islamic State?

“I was offered free counselling at Lender Friend and I really needed that … I am now confident that I can solve my financial problems. I will probably need 10 more months,” says Ana, whose full salary goes to pay her debt. The minimum salary for domestic workers in Hong Kong is currently HK$4,410.

“The root causes of the problem are lack of financial literacy and lack of savings. So to really make a difference we have to attack both of those well and we have to work on both,” King says, noting that they plan to pay for financial literacy courses for borrowers.

King also said that he hoped to take such strategies to other countries in Asia and the Middle East.

David Bishop, a specialist in accounting and law at the University of Hong Kong, agrees that technology could improve the loan industry, but adds “advancement in technology is also why so many of these illegal companies exist and why it is so hard to investigate them. It is very easy to transfer and move money in a clandestine way.”

When maids turn to Islamic State: 5 key events

More than a problem involving financial illiteracy, Bishop says, “this is an issue of coercion, deception and trafficking. And on the government side, just complacency and unwillingness to enforce the rules”.

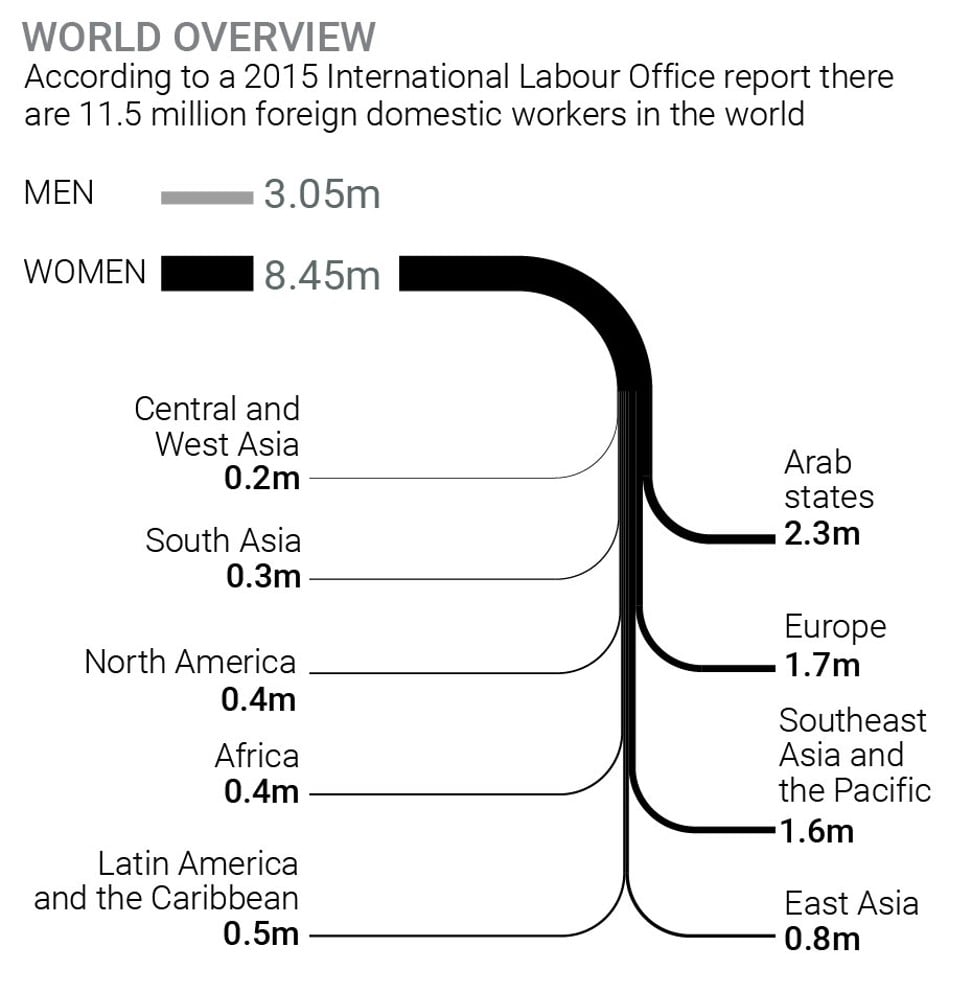

Thousands of migrant domestic workers accumulate debts, some of them unknowingly, that range between US$1,600 and 1,800 per person, a report on modern slavery in East Asia has found.

“The fact that most migrant domestic workers borrowed money from employment agencies to pay fees to these same agencies feeds into the argument that the situation of many migrants resembles debt-bondage, which is a form of modern slavery. The pressure on these women to continue working despite difficult circumstances is often high,” states a report by international social enterprise Seefar.

In Singapore, for instance, Jacqueline Loh, the CEO of Aidha, a non-profit that provides financial literacy and training programmes for foreign domestic workers, says there are “quite a few stories of loan sharks targeting foreign domestic workers, so it is definitely a problem in Singapore, but there is not much data available on its prevalence”.

The Indonesian child maids of Hong Kong, Singapore: why they’re suffering in silence

Clarence Lee, a volunteer manager at the Asian Migrants Credit Union, argues that “financial inclusion is almost as basic as a human right”. The savings and credit cooperative for migrants that was created in 2008, in Hong Kong, is introducing technology to speed up procedures and reach out to more migrants.

“It’s not a single thing, it’s not just financial literacy, or just micro credit,” Lee says.

“Different ethical partners need to exist and come together to protect workers at different spots of their migration journey.” ■