Returning tourism won’t save airlines from coronavirus

- The bad news is piling up for aircraft makers and their parts suppliers – and the white knights they were dreaming of may never turn up

- Do we even want to go back to travelling as much as we used to?

Of course, in a matter of weeks all air travel came to a screeching halt, and I now expect this sector to contract and suffer a long-term impact.

HKG BACK ONLINE FOR TRANSIT

Last week Hong Kong International Airport (HKG) reopened. In normal times, it is one of the world’s busiest airports, catering to 71 million passengers annually, but for the last few months it has been little more than a parking lot for Cathay Pacific’s fleet. Cathay is usually accustomed to transporting more than 100,000 passengers per day, but during the height of the crisis the carrier saw its daily load fall below 500 passengers and warned of a large loss coming. My last flight was in April on a near-empty CX252, dressed in an uncomfortable paper bag.

Under pressure from tourism companies and organisations, governments are pursuing bilateral travel agreements between countries to dodge quarantine rules by creating “travel bubbles” or “air bridges”. These are likely to start coming into place by the end of this month. But with airlines taking new health precautions, travel is going to get more complex and more expensive.

I’M LEAVING ON A JET PLANE

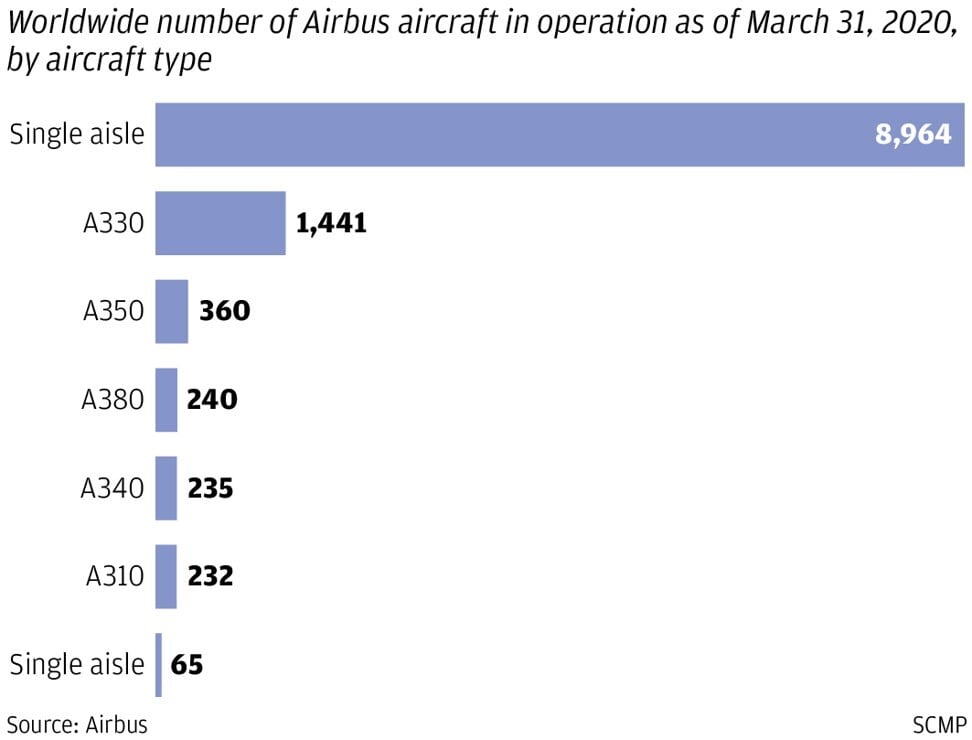

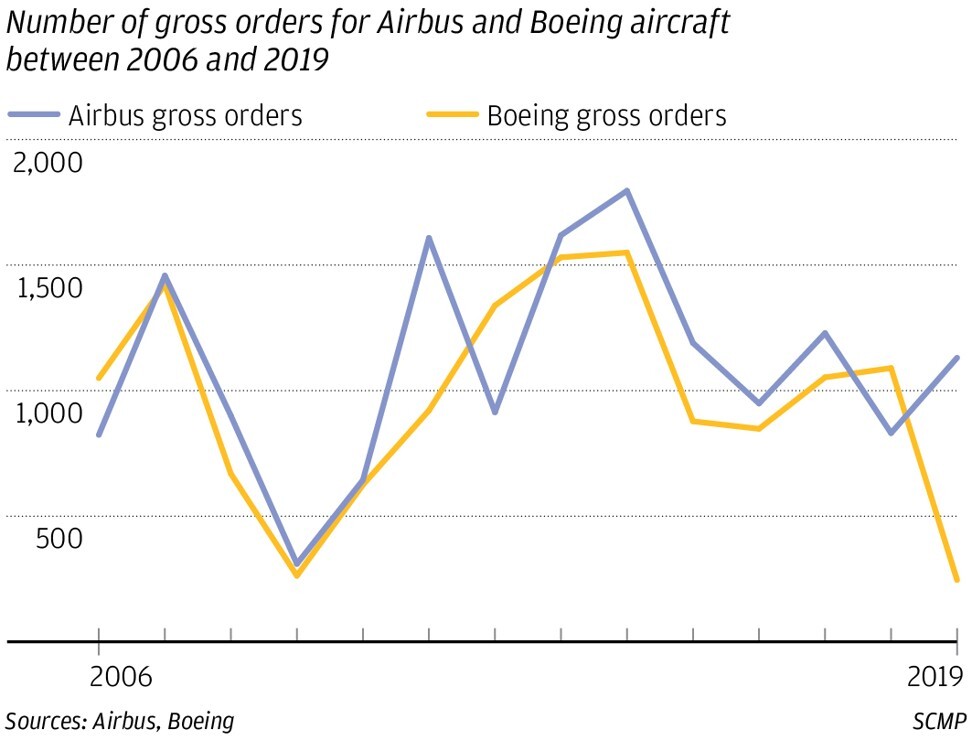

Until last year, about 10 million people worldwide boarded a plane on any given day. And about a tenth of the world’s population has flown at least once. That was the basis for aircraft manufacturers’ bullish passenger projections which posited that over the next 20 years some 40,000 new aircraft would be built at a cost of about US$6 trillion. Passenger aircraft fleets would double. Going into last year, Airbus boasted a production backlog of around 7,500 planes, and Boeing’s backlog was around 5,900 aircraft – and that was after the Lion Air and Ethiopian disasters which killed 346 people. As far as we can tell, Boeing rushed through an upgraded design – the 737 MAX – that could be competitive in the budget airline market, which operates on wafer-thin margins, at the expense of its usually impeccable product quality. And the Federal Aviation Authority didn’t catch it.

Why China, like Japan, needn’t worry about paying all that debt back

CARGO

According to Boeing, by 2018 about 1 per cent of the world’s freight by weight was carried by air, or 34 per cent by value. This represented a massive opportunity. Clearly, the most expensive items would travel by plane, but as freight flights expanded they got so cheap it became possible to fly vegetables from one side of the globe to the other. That is why Marks & Spencer in Hong Kong competes with local supermarkets for fresh vegetables – flown in from Britain.

Coronavirus: why Asia will win the race to economic recovery

However, if I am correct in thinking that supply chains are starting to move closer to their home markets due to this year’s unacceptable supply-chain disruption, a rising salary component in the price of parts and the arrival of an even nastier trade war will cause the demand for air freight to once more stall and prices will fall.

Many airlines, Cathay included, have been able to take advantage of some of the demand by flying passenger planes filled to the rafters with cargo during the lockdown. It isn’t as profitable, but a decent source of income when a firm is in survival mode to avoid lay-offs. This business has kept them going, but they need to start flying people, which is more profitable than cargo.

However, I question whether mass tourism still has a future and if the demand for single-aisle planes is sustainable, for the following reasons:

• Money – the people who relied on cheap tickets for copious holiday travel are likely to be left somewhat poorer as unemployment has rocketed. We may simply not have the money to fly as much as we used to. And flights will certainly be more expensive with fewer people on planes, expensive health precautions and perhaps “seat distancing”, despite the current low price of oil. Business travellers would have been expected to be the first to get back up in the air, but now everyone knows how to use Zoom.

• Politics – governments are likely to focus on domestic tourism to keep spending at home and boost local economies. Foreign policy plays a role as well. And on a local level, many cities have realised the damage mass tourism was causing. Fewer visitors has been a welcome relief – just ask the residents of Barcelona, Venice and Kyoto.

For value investors, Covid-19 can be a crisis and an opportunity

THE COLLAPSED AIRCRAFT MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

In the space of a few months, air travel has come to a grinding halt, with fleets of idle aircraft parked at airports and in deserts, and staff being furloughed or laid off. While parked aircraft don’t need many new parts, they do require a surprising amount of maintenance. As airlines go under, more planes are likely to be fully mothballed or sold.

Boeing shut down all aircraft manufacturing for a time this year, with hundreds of undelivered aircraft parked at assembly plants, and Airbus’ output is down 40 per cent year on year. Certainly, airlines will be back, and those that survive could in time become big winners. But for the next few years, they will have to perform a careful balancing act to eke out profits. That’s almost certainly all bad news for aircraft manufacturers and their parts suppliers, which will suffer a long-term impact and a slower recovery than any other manufacturing industry I can think of. ■

Neil Newman is a thematic portfolio strategist focused on pan-Asian equity markets