Advertisement

Ukraine war: Will Russia’s pivot to Asia and China ties be its fallback option for trade as Western sanctions mount?

- Russia’s efforts since 2014 to lay down a network of trade deals and channels across Asia could act as a fallback amid sanctions over Ukraine, analysts say

- A depreciating rouble and previously established FTAs would pave the way, if China continues to keep the door to trade open

Reading Time:6 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

71

Like many global traders, Indian tea growers association boss M. P. Cherian is closely watching the humanitarian and economic fallout from Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine.

Members of his United Planters’ Association of Southern India (UPASI) are bracing for headwinds, as Russia is a big buyer of Indian tea, purchasing 40 million kilograms of tea annually, with nearly half of this coming from India’s south. Russia’s average annual tea import is around 140 million kilograms.

India, which has refused to condemn Russia – its biggest supplier of arms – is still keeping trade ties intact, even though pressure is mounting as more Western nations and companies sanction business dealings with Moscow.

India-Russia bilateral trade – minus defence purchases – was about US$9 billion in the 2020-21 financial year, a fraction of India’s trade with the United States which exceeded US$100 billion. For tea, Russia’s purchases from India has been growing about 1 per cent a year over the past 10 years, save for 2020 when the pandemic hit.

Advertisement

“The ongoing Russia-Ukraine crisis is a matter of concern … and if tea exports to these two countries are affected, it will have an impact on the Indian tea sector … especially small tea growers,” said Cherian, the association’s president.

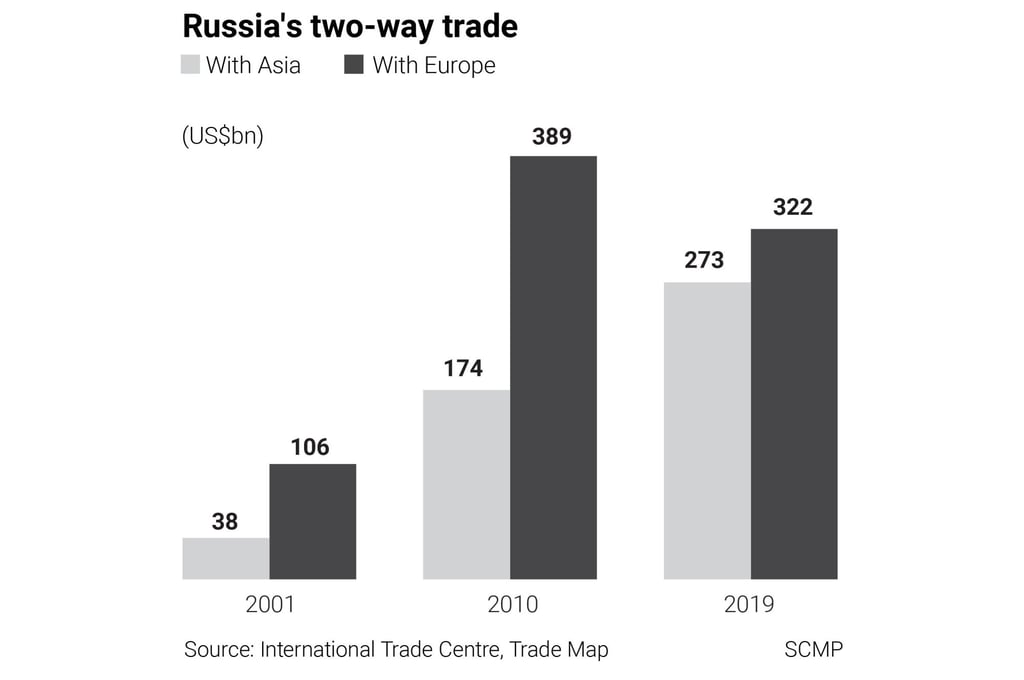

Cherian’s comments reflect how Russia’s trading relationships with all corners of Asia have grown in the last decade. The European Union has long been Russia’s largest trading partner, accounting for 40 per cent of its two-way trade before the invasion. But latest available figures from 2019 before the pandemic shows Asia’s trade – including China – with Russia approaching Europe’s, with both regions accounting for about the same proportion of two-way trade with Russia.

This is a result of Russia’s efforts – since calling for a pivot to Asia just before the annexation of Crimea in 2014 – to lay down a network of trade deals and channels across the region. For some analysts, these relationships will now be Moscow’s fallback plan for trade as sanctions from the West and its allies in the region such as Japan and South Korea hit it hard.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x