From India to Philippines, gas shortages to remain for years as rich nations stockpile LNG

- Amid the Ukraine war, Japan and South Korea have showed a growing willingness to pay top dollar to secure LNG from the US and the Middle East for the winter seasons up to 2024

- Analysts say developing Asian nations will have to increase their dependency on cheaper, dirtier, locally-sourced and imported energy products like coal and fuel oil

Consumers in developing Asian states should prepare for four more years of natural gas shortages because wealthier economies like Japan, South Korea and the European Union have cornered the global liquefied natural gas (LNG) market, according to analysts.

The world’s two biggest LNG importers, state-owned Korea Gas and Tokyo-based Jera, last week both issued tenders for a large number of spot market cargoes, to stockpile for winter and ensure energy security up to 2024.

Japan and South Korea have demonstrated a growing willingness to pay a premium to secure LNG from the United States and the Middle East that would otherwise go to the European Union.

Could nuclear energy be Singapore’s net-zero ‘game changer’?

The EU is scrambling to find alternative gas supply sources to Russia but recently acknowledged the inevitability of shortages this winter.

In the bidding war between Europe and Northeast Asia for LNG cargoes, “the winner will be whichever buyer can pay the highest price”, said Sam Reynolds, an energy analyst at the US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

“The losers will be countries that both depend on imported LNG and lack the fiscal strength to afford higher priced, US dollar-denominated fuels,” he said.

Prior to 2022, mainstream forecasts projected that more than half of global LNG demand growth up to 2025 would come from developing economies in south and Southeast Asia, according to an IEEFA report on August 15.

Those projections were shredded by the tumultuous effect of the EU’s attempts to suddenly wean itself off Russian gas because of political conflict over the Ukraine war, it said.

“Sustained high prices and competition for limited supplies have undermined the economic case for LNG and cut LNG sales in Asia,” IEEFA said.

India’s imports fell by 10 per cent in the first seven months of 2022, according to recent data by Bloomberg New Energy Finance, while Pakistani purchases declined by 6 per cent and Bangladesh by 4 per cent.

Thailand, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are all projected to face substantial gas shortages until 2026, when several major new LNG projects in Qatar and the US are scheduled to begin production.

China cut its spot market purchases by 20 per cent year-on-year, but analysts said it is well positioned because of the multiple long-term LNG import orders it placed during the early years of the Covid-19 pandemic when gas prices were at historic lows.

Asian LNG imports fell by more than 6 per cent year-on-year between January and July.

Reynolds said Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India have cut LNG purchases due to high prices.

Bangladesh has withdrawn from the spot market altogether, while leading Indian importer Petronet LNG last week cancelled a 10-year contract tender.

“Lack of fuel has in turn resulted in severe fuel and power shortages in all three markets and stunted economic activity of key sectors,” Reynolds said.

Asia’s energy future thrown into doubt as EU’s Russia boycott takes shape

Many Asian LNG importers have had trouble securing any supplies in recent months, rendering billions of dollars worth of infrastructure increasingly inoperative.

Russia’s Gazprom reportedly defaulted on a long-term contract to supply India’s biggest gas distributor Gail after the Singapore-based trading arm of the Russian firm was hit by Western sanctions in June.

State-owned Pakistan LNG received no bids at all in response to gas import tenders issued for July to September, and is expected to struggle to find suppliers for a six-year term contract it offered earlier this month.

“Not all countries have the ability to import LNG” because it costs hundreds of millions of US dollars to build the infrastructure and years to obtain approvals, said Toby Copson, the Shanghai-based global head of trading and advisory at Trident LNG, a gas trading and shipping firm.

Many developing Asian economies that “do have the ability and can buy are being priced out of the market, the most notable being Pakistan”, he said.

“This has left the country in a dire energy situation and caused rolling blackouts as of late,” Copson said.

Analysts said the situation augurs ill for the almost US$97 billion of LNG import projects currently under development in Asia.

Prospective LNG markets like Vietnam and the Philippines, which are expected to import their first volumes this year, now face an “urgent risk of exposing their economy to volatile, unaffordable imported gas”, IEEFA analyst Reynolds said.

“Ultimately, households and businesses in developing countries will be forced to bear the costs of the global energy crisis,” he said.

Can Vietnam revive flagging wind, solar to transition to clean energy?

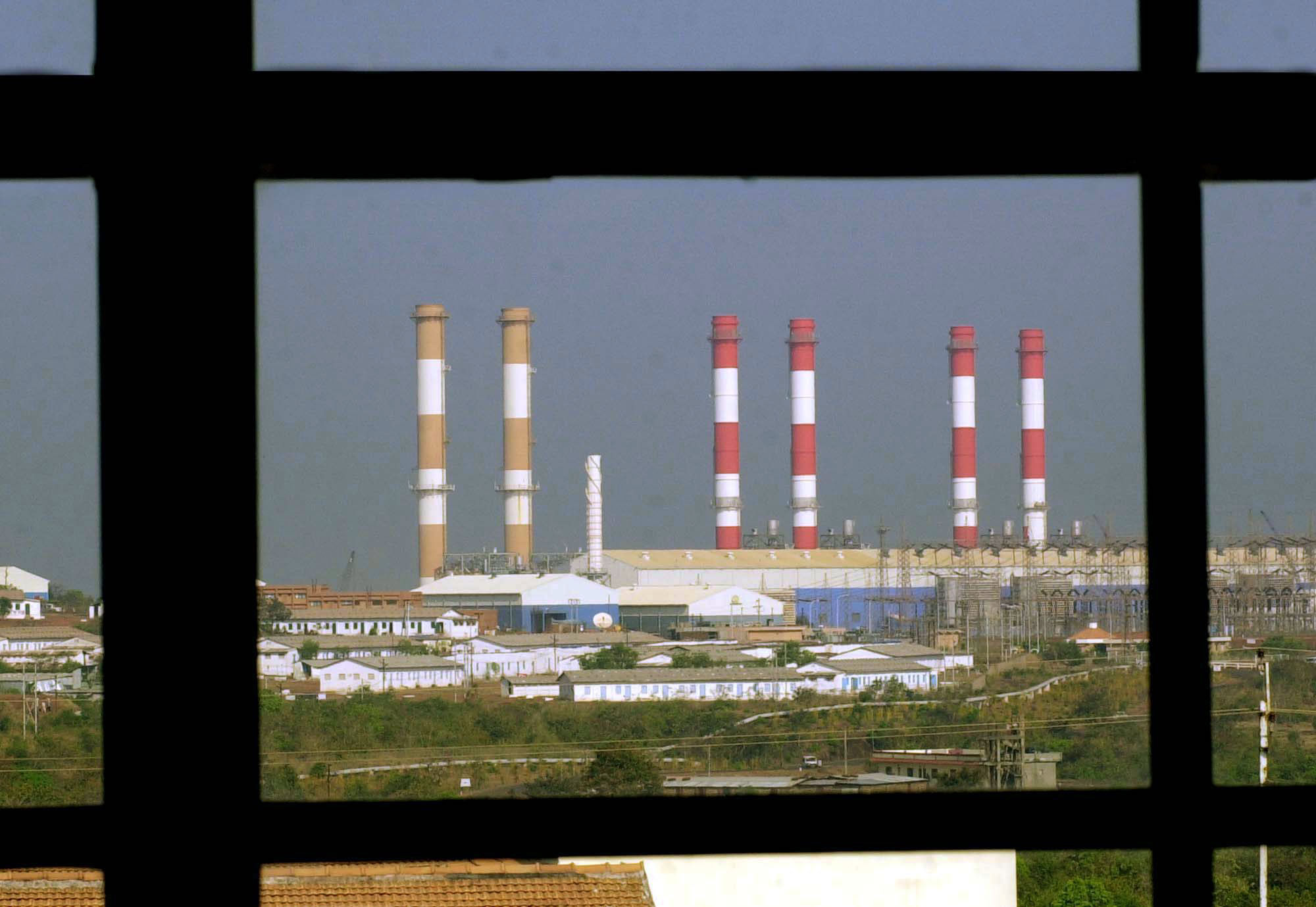

Analysts said developing Asian countries will have to increase their dependency on cheaper, dirtier, locally-sourced and imported energy products like coal and fuel oil.

This will impact their “speed of change for transition” to renewable energy sources like so-called green hydrogen projects currently being developed as a replacement for gas from 2030 onwards, Copson said.

“The poorer countries really have no option for greener fuels and, oftentimes, the cost of infrastructure is a barrier to entry itself,” he added.

The LNG bidding war between the wealthy EU and northeast Asian nations is “leading to longer dependence on coal and less green alternatives” for developing Asian countries, Copson said.

“In turn, they will have issues in keeping the lights on, thus slowing industrial economic ability,” he said.

Other wealthier nations have had longer for these fuels to develop and are better placed fiscally to implement a transition, part or otherwise.