Western friendshoring benefits Malaysia amid US-China rivalry, but could hurt global economy: trade minister

- A complete decoupling among the superpowers would affect the world economy, says trade minister Tengku Zafrul Aziz

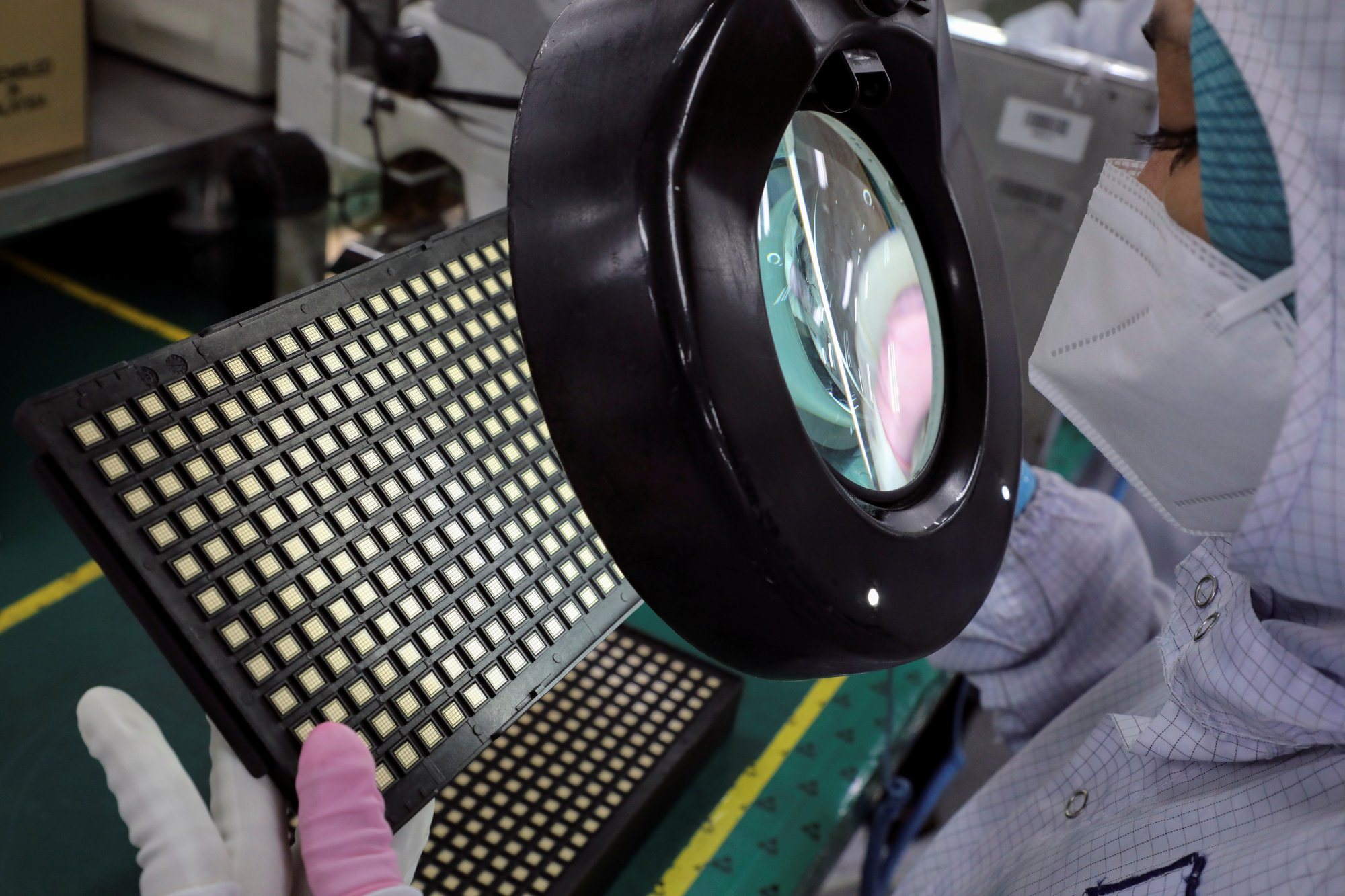

- Malaysia’s semiconductor industry is expected to continue growing in the short term as US companies look to boost their presence in the country

“Companies are relocating, reshoring, friendshoring … but in the longer term, I personally believe that any hindrances or obstacles to global trade will not be good for the global economy,” he said.

Still, Zafrul said he expected the country’s vital semiconductor industry to continue to grow in the short term, principally because of US-China tensions.

Malaysia accounts for some 13 per cent of global chip assembly and packaging, and 8 per cent of all semiconductor trade passes through the country.

Zafrul said those figures were likely to rise further, as US companies make use of new grants and subsidies for chipmaking and research to mass produce leading-edge semiconductors, including in so-called friendly countries.

“[The Chips Act] will mean that we will grow because it also includes incentives for working with friendly countries,” Zafrul said, noting that Malaysia supplies 25 per cent of US semiconductor needs.

In May last year, the US and Malaysia signed a bilateral memorandum of understanding to strengthen semiconductor supply chain resilience.

Asean emerging as China trade alternative but won’t be a replacement: experts

“So we are an integral part of the supply chain … I can’t reveal the names but we are about to announce this year that there are one or two [US companies] that are increasing their presence in Malaysia because of the support they are getting from their own government and also because of what is happening between” the US and China, he said.

Asked about the likely reaction by Beijing to Malaysia’s significant role in satisfying US semiconductor needs, Zafrul noted that while Chinese companies in the industry did operate in the Southeast Asian nation, “they are not really as dependent on us”.

Anwar’s new administration includes the United Malays National Organisation that Zafrul is part of, a party which the current prime minister had until recently been fiercely opposing for more than two decades.

That meant that the Malay nationalist Perikatan Nasional bloc – of which Zafrul was also a part – was kept out of office after 33 months in power from March 2020 to last November’s vote.

Zafrul was finance minister under two different prime ministers during this period, and Anwar in November appointed him to head the Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

In the interview, Zafrul said investor confidence in the new Anwar administration was exemplified by how Amazon confirmed a US$6 billion investment in data centres in Malaysia only after the election. Negotiations for the deal began in 2019.

“To be frank, we were working on the deal [last year]. I was finance minister working with the Ministry of International Trade and Industry … we could have sealed the deal but they wanted to be sure on certain issues,” Zafrul told This Week in Asia.

“They are diplomatic people, they were not going to say, ‘I want to wait’, but we know one of the reasons they wanted to wait was because of the general election,” he said.

There were no signs of the kind of equity flows that happened during the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, and markets seesawing in recent weeks were down to confidence levels, Zafrul said.

He noted that the risk of contagion was minimal as small banks – seen as vulnerable if they have big loan books at interest rates fixed below current levels – made up only a small percentage of the whole banking system.

On whether Asian central banks should consider slowing interest rate increases, or rate cuts to stimulate slowing growth, Zafrul said as a former finance minister he would “fully support” such moves.

The Malaysian central bank on March 9 kept its benchmark rate unchanged for a second consecutive meeting, and there have been growing calls from within Anwar’s government for the freeze to continue amid growth concerns.

Last year, Bank Negara Malaysia increased rates by a total of 100 basis points from a historic low of 1.75 per cent as it sought to tame inflation amid robust growth.

Given external challenges to the economy and inflation being under control, the use of monetary policy was not required, Zafrul said, adding that inflation at low levels was needed, among other things, to ensure wages rise.