Indonesia urged to study feasibility of extending China-backed rail line as Japan mulls exit

- Indonesia plans to give China the project to extend the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway line to Surabaya

- Japan could pull out of the project to protect its brand, as analysts urge Indonesia to go with whichever country offers the best rate given its limited resources

Indonesia has been urged to launch an open bid and independent feasibility study for an extension of a mega rail project that could involve China, after Tokyo raised fears it might pull out to protect “the Japan brand”.

The US$7.2 billion Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway project is part of China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative in Indonesia. The Indonesian government now aims to extend the line all the way to Surabaya in East Java, the country’s second-biggest city some 781km from current capital Jakarta.

President Joko Widodo’s initial plan in 2019 was for Japan to build a semi-high-speed train connecting Jakarta and Surabaya via the northern part of Java Island, while China was to develop the southern railway link. But he now thinks it is more economically sustainable to give China the project to extend the rail link from Bandung to Surabaya.

Japan has signalled that it may step away from the project to prevent any technological issues, according to the country’s cabinet secretary for public affairs Noriyuki Shitaka.

“If you mix two technologies, I don’t know whether it will work well or not. For example, we cannot be responsible for Chinese high-speed rail projects, especially if there is a problem. If we work together, there is such a possibility,” Shitaka said on September 7, as cited by The Jakarta Post.

Indonesia delays opening of China-funded railway amid safety concerns

Japan was being careful so as not to damage “the Japan brand” as it had no knowledge of the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway system or composition, Shitaka said, adding that any collaboration would have to be between private companies.

Sutanto Soehodho, a professor in transportation at the University of Indonesia, agreed that the Jakarta-Bandung railway should be extended to Surabaya to make the fast train economically more sustainable, but said the government should conduct a feasibility study and create a basic engineering design before making any decisions.

“The feasibility must really be studied if we want to extend to Surabaya, not just because it has been built by China so we continue with China,” he said.

If Indonesia worked with Japan, who was known for being “very careful in its planning”, the collaboration might not result in a cost-overrun situation like what happened in the Jakarta-Bandung project, Sutanto added.

To complete the Jakarta-Bandung line, Indonesia had to use the state budget, something Widodo had vowed he would not do. The project costs overran by US$1.2 billion, and Jakarta had to borrow from the China Development Bank (CDB) with an interest rate of “more than 2 per cent”, Indonesia’s coordinating maritime affairs and investment Luhut Pandjaitan said in June.

Luhut claimed Jakarta was pleased with the CDB rate, as it was “lower than the global interest rate”, but analysts beg to differ.

Sutanto pointed out that the figure was 20 times higher than the 0.1 per cent rate given by Japan International Cooperation Agency when Indonesia built the first corridor of the mass rapid transit subway system in Jakarta, which cost around US$1.1 billion.

“If China can give us a better offer, that’s fine; if not, should we still work with China, which still offers a high loan interest [rate]?” Sutanto said.

Is China-funded Indonesia high-speed railway finally on track to launch?

Bhima Yudhistira, executive director at Jakarta-based think tank Center of Economic and Law Studies, said there was “no urgency” for Indonesia to build another high-speed rail link, as the country’s financial resources were limited.

“I’m worried about our narrowing fiscal space, with next year’s debt interest burden of 500 trillion rupiah and increased social protection spending, as well as [budget for] the new capital development … if we insist on extending the link to Surabaya now it will be too heavy for our state budget,” Bhima said.

Jakarta claims there is room for savings now that it has had first-hand experience of building infrastructure with China. Luhut said in June that Indonesia’s downstreaming policy meant materials could be sourced domestically instead of having to import them.

Downstreaming refers to Jakarta’s effort to boost the value of its minerals, such as nickel, bauxite and copper, by banning exports of raw minerals and requiring miners to set up local processing facilities.

Not enough passengers

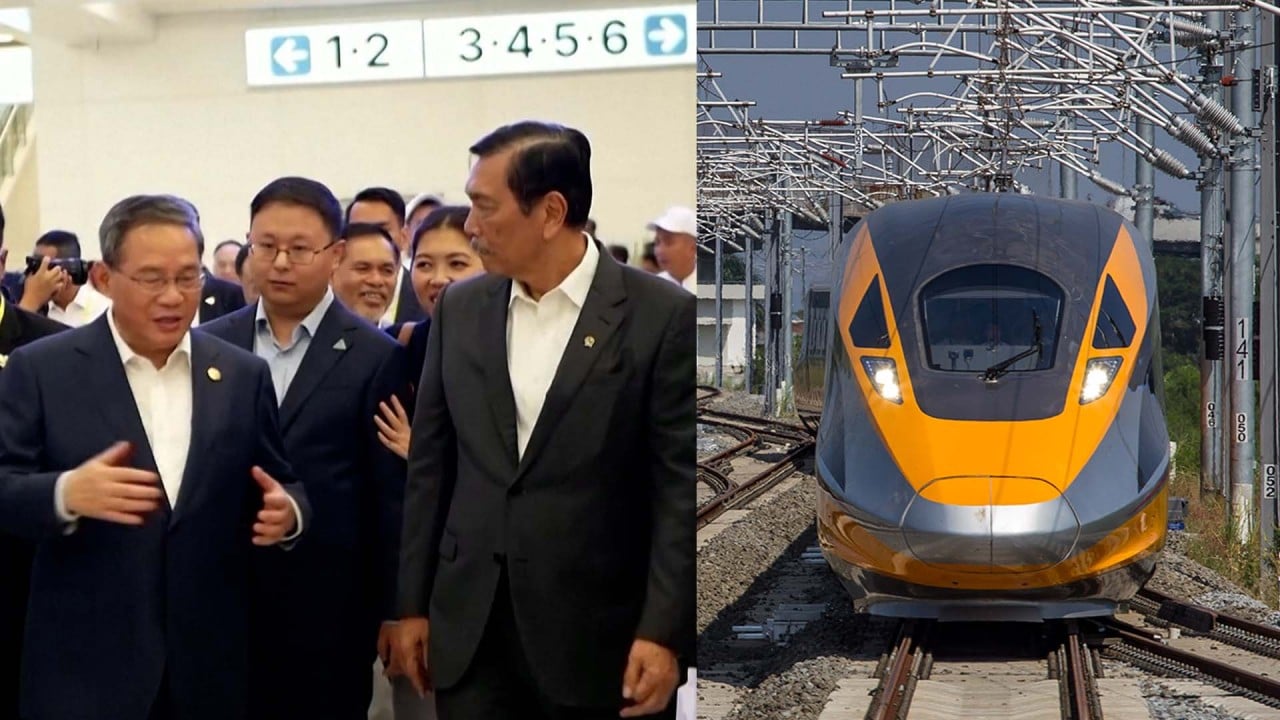

Japan’s comment came a day after Luhut discussed the extension plan with China’s Premier Li Qiang last week on the sidelines of the Asean summit. Luhut said Li’s response to the plan was positive.

“They are also happy if they can get involved … With their experience of having built 41,000km of tracks for fast trains, I think it is worth considering,” Luhut said on September 6, after he and Li hopped on a trial run of part of the Jakarta-Bandung line.

According to Luhut, Li was “very satisfied” with the train, which is yet to receive an operation permit from Indonesia’s transport ministry, pending the result of safety checks. “He said the quality was the same [as] the ones in China,” Luhut said.

Widodo, who tried the train on Wednesday, said the ride was “comfortable”.

“It’s comfortable and at a speed of 350 [km per hour], I don’t feel [the speed] at all, either when sitting or when walking. Yes, this is civilisation. [It’s all about] speed, speed,” he said.

According to Widodo, the public can try the train “in early October”, marking yet another delay in the inauguration of the tax-funded train. Widodo asked authorities not to rush their assessment of the safety aspects of the train, which was 92 per cent complete.

The new service is expected to help clear up the notorious traffic along the Jakarta-Bandung toll road.

“[By using the train] we can reduce traffic jams and air pollution. Every year we lose more than 100 trillion rupiah due to traffic jams in [Greater Jakarta area] and Bandung. We hope that people will switch from private cars to fast trains,” Widodo said.

Getting more passengers on board might not be as easy as Widodo hoped, as the fast train must compete with other cheaper modes of public transport – a slower train service, intercity buses and minivans currently ply the route to Bandung.

KCIC, the China-Indonesia joint venture behind the Jakarta-Bandung railway project, said it slashed its daily target of passengers from 31,000 to about 10,000 as it would not be able to serve 68 trips a day in its initial operation.

The existing regular train service, Argo Parahyangan, currently ferries 12,000 passengers daily, with trips priced around 120,000 rupiah (US$7.80). This is considerably cheaper than the fast train’s planned fare of 250,000 rupiah (US$16.30).

The regular train makes stops in the city centre of both Bandung and Jakarta, in contrast to the fast train, which stops at Padalarang and Tegalluar, some 20km and 17km from the Bandung centre, respectively.

The Jakarta-Bandung railway is Southeast Asia’s first high-speed line and is expected to cut travel time between the two cities from three hours to about 40 minutes.