Malaysians to pay more for staples as weak ringgit enters ‘uncharted territory’ amid global slowdown

- Malaysia’s central bank has limited options to prop up the ringgit as its weakness is linked to external factors, economists say

- A cheaper ringgit, however, can benefit Malaysia’s economy in sectors such as exports and tourism

An imported vegetable widely used in Malaysian kitchens, the pungent bulb is now around 16 ringgit (US$3.34) a kilogram, almost double its 9 ringgit price just a month earlier, he said.

“It’s really expensive now, but there’s nothing we can do about it,” said Subramaniam, as he stacked onions in his sundry shop in Kuala Lumpur. “Our suppliers raised their prices and we have to do the same.”

Malaysia’s subsidy problem: help for the needy or financial drain?

The ringgit fell to 4.760 to the dollar on October 19, according to Bloomberg data, prompting concerns it may plunge to levels last seen in 1998 when regional currencies tanked due to aggressive foreign-exchange speculation that triggered the Asian financial crisis.

Malaysia’s central bank on Monday said the economy was “not in crisis” despite the ringgit hitting a record low, and that it would take all necessary measures to maintain a “smooth and controlled adjustment of the ringgit”.

“It is different from what we experienced in the past,” Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) Governor Abdul Rasheed Ghaffour told reporters on the sidelines of an event.

The ringgit has fallen more than 8 per cent against the US dollar so far this year and has been Asia’s worst performer, second only to the Japanese yen.

It fell further to 4.787 on Thursday afternoon, and analysts think Malaysia’s currency has yet to bottom out.

Saktiandi Supaat, Maybank’s head of foreign exchange research, said the ringgit is expected to hit the 4.8 level – very close to its historic low of 4.885 to the dollar on January 7, 1998 – before it could regain some strength.

The risk of a further decline in the currency will remain high as long as there are no improvements to these external factors, Saktiandi said, though any efforts by Malaysia’s government and the central bank to prop up the ringgit could go some way to help.

“We are in uncharted territory,” Saktiandi told This Week in Asia.

Continued slump

The ringgit is currently the closest it has been to its all-time low, but it is not the first time in recent years that it has hovered near that level.

In September last year, it fell to 4.568 against the US dollar, prompting Malaysia’s central bank to assure markets that its policy priority was to sustain economic growth and strengthen domestic economic fundamentals to weather the currency downturn.

Malaysia makes ‘aggressive’ dedollarisation push for China trading

More recently, BNM in July said it would intervene in the foreign-exchange market to stabilise the ringgit following what it described as “excessive” losses that did not reflect the country’s economic fundamentals.

Abdul Rasheed on Monday said the central bank had an “array of market measures” that it could deploy to bolster the ringgit when needed.

Investors generally accept some degree of intervention by regulators in the Southeast Asian nation and many of its regional neighbours where currencies are traded in managed-float exchange regimes, said Yeah Kim Leng, an economics professor at Sunway University in Malaysia.

But any ban on offshore trading of the ringgit, as BNM did in 2016, would be a step too far due to its adverse effects on investor confidence, and capital and financial flows, Yeah said.

“It could also send the wrong signals that the [Malaysian] economy is in crisis,” he said.

Raising Malaysia’s overnight policy rate now would be of little consequence for the ringgit’s performance as BNM’s key rate tracks inflation and not the currency’s fluctuations, they added.

“It is best to focus on things that will improve market confidence, such as fiscal discipline,” said Mohd Afzanizam Abdul Rashid, Bank Muamalat’s chief economist.

Winners and losers

The ringgit’s weakness does not necessarily mean doom and gloom for the Malaysian economy, as a cheaper local currency typically benefits exports and sectors such as tourism.

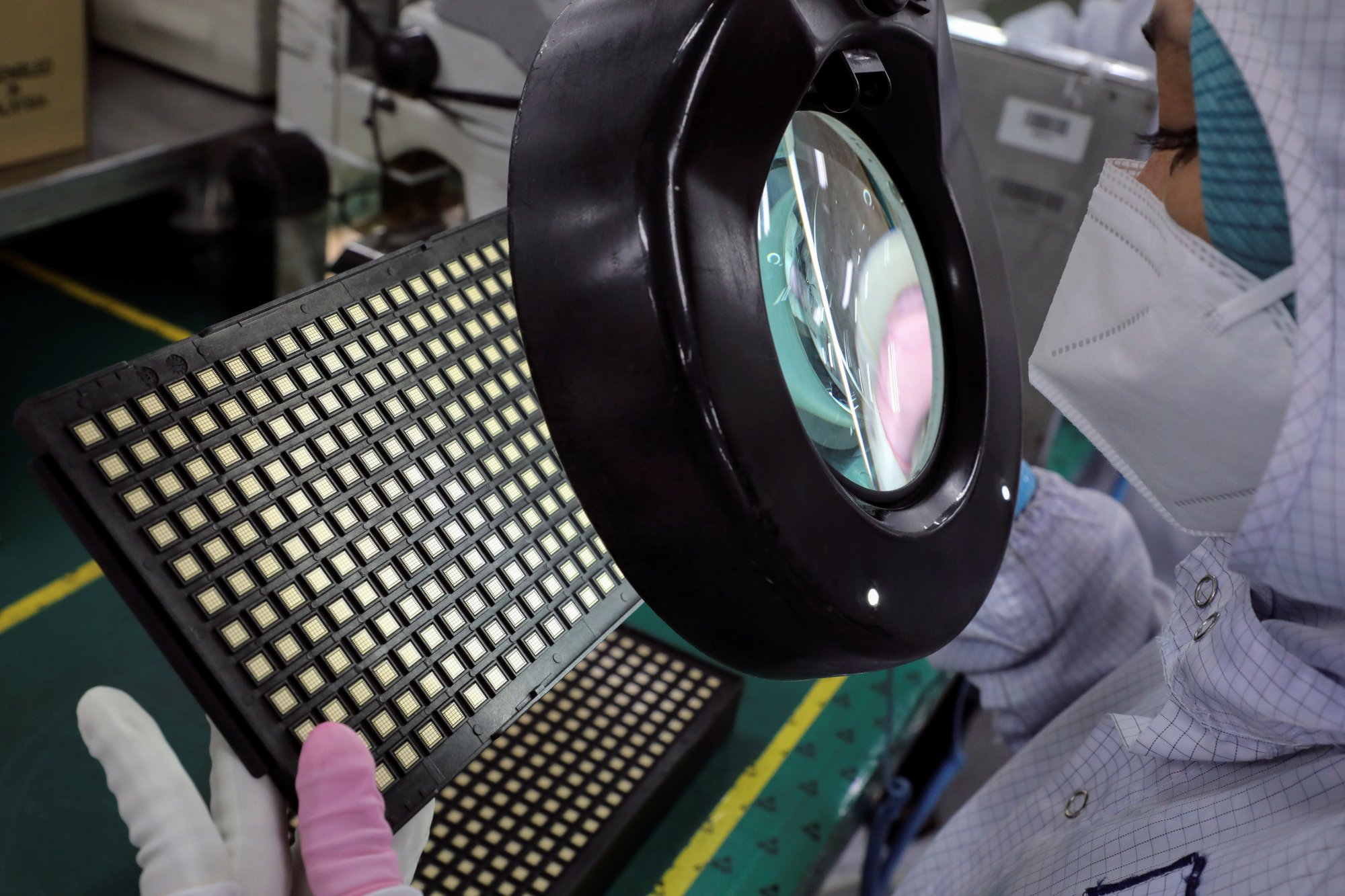

Malaysia’s manufacturing sector, in particular, would be one of the biggest beneficiaries of a depreciating ringgit, as most of its trade is carried out in US dollars.

But demand for some of the country’s key exports such as semiconductors has been sluggish. Overall exports fell 16.5 per cent year on year in September, marking seven months of consecutive declines, mainly due to a global weak appetite for electrical equipment, electronics and commodity shipments.

“We are experiencing a depreciation [in the ringgit] which increases export competitiveness but within an overall pessimistic export environment,” said Cassey Lee, a senior fellow and coordinator for regional economic studies at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Maybank’s Saktiandi said any boost to exports due to a weak currency would only be helpful for the economy if structural changes are also implemented to raise productivity, which has long been lagging in Malaysia.

Malaysia sees ‘a lot of opportunity’ for more investment from China

On the flip side, currency weakness also translates into costlier imports and this would have a direct impact on the cost of living, experts say.

This presents a challenge for the government in containing potential spikes in the cost of staples such as rice and chicken, as many local poultry farmers use imported feedstock.

Mohd Afzanizam of Bank Muamalat said the ringgit’s continuous weakness “would result in imported inflation becoming more prevalent, and could potentially slow down the economy as consumers would be cautious in their spending”.

Economists warned of the lingering risks from the Ukraine and Israel-Gaza wars, which could further weaken the ringgit, especially if there is any escalation.

However, the ringgit could rebound if economists’ expectations of the US dollar tapering off at the end of the year and Fed easing next year are realised.

Until that happens, Malaysia’s government has to ensure it has some levers to help mitigate any price shocks arising from the ringgit’s weakness, ISEAS’ Lee said.

Earlier this month, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim proposed a targeted subsidy programme under his 2024 budget in a bid to narrow the government’s subsidy bill, which is estimated to hit 81 billion ringgit this year.

“The best the government can do now is try not to touch its subsidy programme because that might worsen [the cost of living],” Lee said.