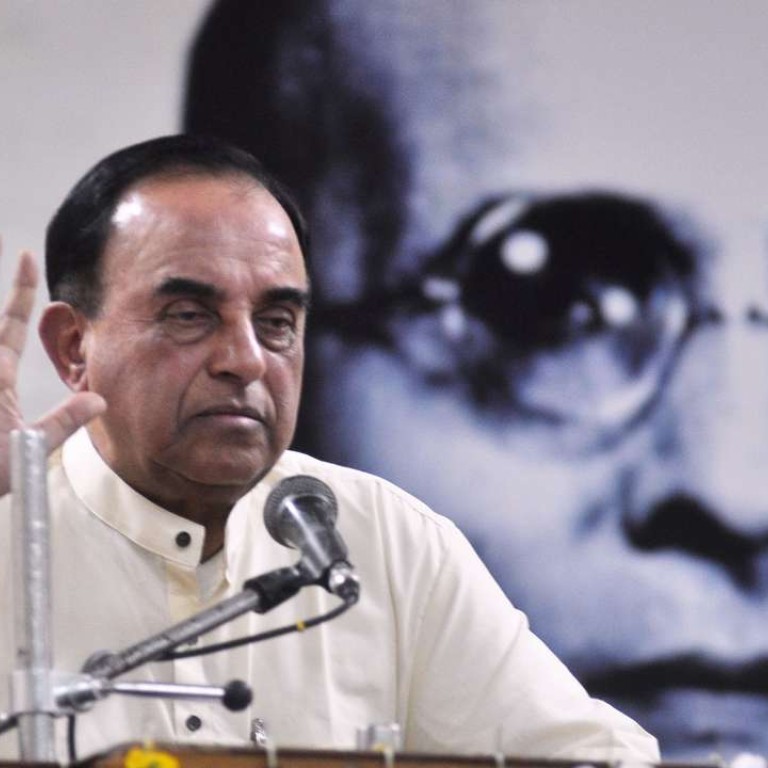

India’s China policy off target, says Modi’s Mandarin-speaking ‘guided missile’

Delhi’s go-to guy for talking to Beijing is one of the few Indian leaders who openly advocate closer ties. Maverick he may be, but there’s reason to believe he’s not alone

“Indian and Chinese brains must be very differently wired,” China historian John Fairbank quipped to Subramanian Swamy one wintry morning in Harvard circa 1963. “I have never seen an Indian who has managed to learn Chinese.”

That little joke was enough to get young Swamy to take up the challenge of learning Mandarin. Having finished his PhD in economics in one and a half years, he had plenty of time on hand. He learnt Mandarin in six months, he says, after which Harvard asked him to teach a course in Chinese economic history.

Modi’s key aide blames poor planning for India’s currency crisis

Thus started the 76-year-old maverick parliamentarian’s long association with China, marking him out as a rare Indian politician with a deep understanding of China and extensive contacts in China’s power circles. In the course of the 40-odd years in public life that would follow, Swamy would earn a reputation as a crusader against corruption and unpredictable muckraker and litigant par excellence. He played a major role in the court case against the multibillion-dollar mobile telephony licensing scandal in the last Congress-led government, which paved the way for the rise of Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to power in 2014 and gave him a cult following among BJP cadres. He is now doggedly pursuing an embezzlement lawsuit against Congress president Sonia Gandhi and her son Rahul.

But his deep China connections would also make him a go-to guy in Delhi to communicate with China. In 1978, he was the first Indian politician to be sent to China to restart dialogue after the 1962 border war that saw all relations broken off. And it was his meeting with Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平) in 1981 that would prompt China to reopen the sacred Kailash-Manasarovar route in Tibet (西藏) for Hindu pilgrims.

When Xi meets Modi, a little less love this time

A straight talker, Swamy is one of the very few Indian leaders who openly advocate better relations with China. In a country where China is widely viewed with suspicion and the political class is wary of appearing even remotely pro-China, Swami’s China-friendly worldview was never going to be easy. But, of late, it seems to have got even tougher. After years of rapid rapprochement, there are signs the two Asian giants may be drifting apart. India resents China’s forays into the Indian Ocean, blames it for blocking its entry into the elite Nuclear Suppliers Group, and for siding with Pakistan. China has been carefully watching India flirt with the South China issue and its overtures to the US and Japan.

“At this point, the Chinese are only interested in one thing: are you independent or not? Are you joining the US axis or are you on your own? We have failed this test,” Swamy told This Week in Asia last week.

In May, Swamy was in China on a 10-day visit at the invitation of a think-tank of China’s foreign ministry. As he does on his yearly trips to China, he met senior leaders, exchanged views and took the pulse. “We think Indians are sentimental, but the Chinese are even more so. And right now, they are not happy with us,” said Swamy. “I have conveyed this back home, I have made it clear to my government and my party that we have no business in the South China Sea. It’s a dispute between the parties involved. Why are we being dragged into it?”

Why China is caught in India-Pakistan crossfire

It’s plain-speaking like this that makes the articulate Harvard economist stand out in a milieu of mostly underwhelming politicians. In recent days, he has called India’s venerable tycoon Ratan Tata “most corrupt”, defied popular mood to campaign against “rock star” central bank governor Raghuram Rajan, has called Rahul Gandhi “uneducated”, and last week let fly at Finance Minister Arun Jaitley for making a hash of Modi’s decision to replace high-denomination bank notes with new ones.

The finance minister is a pet hate since it’s no secret that Swamy would rather have that job. On a recent trip to Beijing, when Jaitley switched from Indian politicians’ preferred garb of kurta-pajama, Swamy tweeted to his 3.3 million followers: “BJP should direct our ministers to wear traditional and modernised Indian clothes while abroad. In coat and tie they look like waiters.”

Neville Maxwell discloses document revealing India provoked China into 1962 border war

Potshots like that have often left his own party squirming and reinforce his image as a loose cannon. But more careful students of New Delhi’s Byzantine politics believe Swamy has not been acting on his own in his battles against Rajan or the Gandhi family, or in his current drive to build a Hindu temple at a disputed site where a mosque was torn down by Hindu fanatics in 1992. In every instance, they say, his action benefits the ruling dispensation without it having to take a politically inconvenient position. With friends across party lines, Swamy is, after all, the ultimate Delhi insider – hardly the profile of a lone crusader. More a “guided missile”, as Outlook magazine put it in a recent cover story.

But if his words and deeds do indeed reflect the thinking of his party, then China-India ties aren’t probably the wreck they seem at the moment.

Swamy’s views about the 1962 war, a sensitive issue for Indians, who hold China responsible for the war, may seem sacrilegious but are known to be shared by many in the party – secretly. “The border clash was avoidable but [the then prime minister Jawaharlal] Nehru had received encouragement from the US to take advantage of China’s misery from the drought and famine,” said Swamy.

On the Dalai Lama, an extremely touchy issue for the Chinese, Swamy is just as blunt. “He must discontinue this political apparatus [in India]. As a religious leader he is warmly welcome in India but the present dispensation [his government in exile in India] is an obstacle to good relations just as is China’s lenient attitude to Pakistan giving sanctuary to trained Islamic terrorists.”

Border dispute an obstacle to building trust between China and India

Much to Beijing’s chagrin, New Delhi has just cleared the Dalai Lama’s first visit to an area that China claims as its own territory. The move came on the heels of India’s failure to garner Chinese support for both its entry into the nuclear suppliers’ club and securing a United Nations ban on a Pakistan-sheltered terrorist wanted in India.

Swamy’s views may seem to be at odds with the official Indian position. But to those given to reading the tea leaves of regional geopolitics, the hardening stance on Tibet could well be a sign of India doubling down on a key bargaining chip with China. In which case, it would be safe to bet that Swami is not talking through his hat.

Debasish Roy Chowdhury is deputy editor of This Week in Asia