Shinkansen: India and Japan’s silver bullet for a rising China

Why the Japanese developed Mumbai-Ahmadabad high-speed rail line is far more than just a bullet train ...

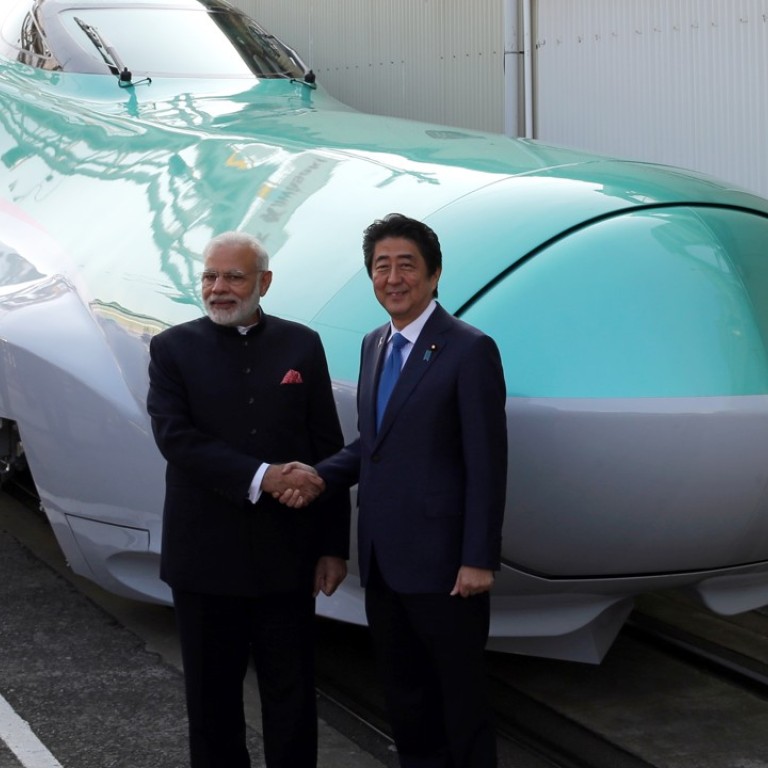

The inauguration this week of India’s first high-speed rail corridor between Mumbai and Ahmadabad, using Japanese technology and financing, has a geostrategic significance that transcends its economic worth. It amplifies the growing closeness between India and Japan at a time when both nations are struggling to find their footing in an Asia being re-fashioned by an ascendant China.

New Delhi and Tokyo have long-standing territorial disputes with China. Both are concerned about Beijing’s deepening economic clout across the region as Chinese investments in infrastructure and connectivity pour in. Within this context the Mumbai-Ahmadabad bullet train embodies the balancing act that India and Japan believe is necessary to prevent Chinese hegemony in Asia.

Perhaps no country is as closely associated with bullet trains in the global imagination as Japan.

Since October 1964, when the first high-speed line reduced the time it took to cover the 552km distance between Tokyo and the commercial centre of Osaka to four hours (today it is down to 2 hours and 22 minutes), the Shinkansen has emerged as the symbol of Japan’s post-second world war metamorphosis into an economic superpower. It encapsulates the archipelago’s engineering might and almost preternatural standards of safety and punctuality. Japan’s Shinkansen have carried more than 10 billion passengers to date, without a single accident or casualty and an average delay of less than one minute.

Yet, despite this admirable track record, Tokyo has struggled to export its bullet train know-how. Before India signed up, Taiwan had been Japan’s only successful sale.

The greatest challenge to Japan’s ambitions is the emergence of China as the new emperor of the super fast train. Over the past decade China has created a 22,000km high-speed rail network, dwarfing Japan’s in size and speed of development. It boasts the world’s fastest train, the Shanghai Maglev that hits speeds of 430km. And China’s technology is also cheaper, making it an attractive proposition for the cost-conscious developing and middle-income countries of Asia.

11 projects that show China’s influence over Malaysia

In 2015, China pipped Japan to the post at the last minute, by securing a high-speed rail project in Indonesia, that had been considered by Tokyo to be in the bag. In the years since, land acquisition problems have stalled the project. Behind the scenes, Japanese officials feel vindicated, claiming China has no proper business plan and is making promises it cannot keep. They also stress their safety record in contrast to China, where a high-speed crash in 2011 killed 40 people.

Regardless, China has also beaten Tokyo to becoming Thailand’s choice of partner for its first high-speed rail line, permissions for which were granted by Bangkok this month. The two countries are further facing off in the bid to win contracts for the Singapore-Kuala Lumpur and Thailand-Malaysia high-speed projects.

Until recently, China’s competitive pricing coupled with its promises of speedy construction, might have inclined India towards partnering on some high-speed projects. In light of recent geopolitical developments, however, this seems less likely. Sino-Indian relations remain tense following a two-month military stand-off in Doklam, near the India-China border. Beijing’s support for Pakistan’s planned economic corridor, which would pass through parts of Kashmir claimed by India, has also raised concerns in New Delhi.

Puffing across the ‘One Belt, One Road’ rail route to nowhere

India’s increasing unease with its northern neighbour is a strategic opportunity for Japan. Tokyo is aware it needs allies to fend off the China-challenge, but few are at hand. India is the only candidate in the region large and powerful enough to fit the bill.

“India is not Indonesia or Thailand. It is a great nation, totally autonomous,” said Hiroshi Hirabayashi, former ambassador of Japan to India and author of the recent book India: The Last Superpower. “It does not need to submit to Chinese pressure,” he concluded.

Tomoyuki Nakano, the Director for International Engineering Affairs of Japan’s Railway Bureau, is confident of ironing out any problems relating to climatic differences, the possibility of electrical blackouts, as well as dust and environmental conditions.

Do Malaysia and Singapore really need a high-speed rail link?

But in India, concerns pertaining to costs and safety persist. Profitability, in particular, is a notoriously hard ask for high-speed train networks. The Japanese-developed bullet line in Taiwan for example, has been mired in debt since opening in 2007. For a high-speed line to succeed, ticket prices and passenger volume need to be high. It costs about US$130 for a one-way Shinkansen ticket from Tokyo to Osaka. And more than 350 trains operate on this line daily, ferrying 163 million passengers a year.

If it succeeds it would pave the way for more Japanese investment in critical Indian infrastructure, boosting trust and easing cooperation in third countries as well. Japan has cutting-edge technology and capital to invest. India provides a large market and a growing economy in need of technological know-how and investment. The two democracies are further bound together by their need to stand up to a common rival: China.

But if it fails, it could indicate other snags that a Tokyo-New Delhi éntente might derail on. In many ways Japan and India are cultural misfits. But Nakano of Japan’s Railway Bureau is sanguine. “When we had Indians coming here [to Tokyo] for training, I noticed some of them were quite late. But after two weeks in Japan they became very punctual,” he concluded. ■