From Sars to Covid-19, what lessons has Singapore learned?

- The 2003 Sars outbreak was a ‘wake-up call’ for the Lion City not to let its guard down regarding infectious diseases, experts say

- Since then, Singapore’s advances in virus research, improved agency tie-ups, and decisive action by officials have equipped it to better battle the coronavirus

A shift in priorities in the city state’s health care system over the past two decades could explain why health professionals were unprepared for the outbreak and the sweeping impact it had, said health economist Phua Kai Hong.

“In our public health schools, we saw a trend of a decline in infectious diseases. Most of our doctors and training then shifted towards chronic diseases and ageing,” said Phua, who was an associate professor of public health administration at the National University of Singapore during the Sars outbreak. “But new infectious diseases came back with a vengeance and Sars was a good example.”

More than 230 people in Singapore were infected with Sars, which killed 33 patients over three months. Since then, the country has upped its game and taken a more proactive approach when infectious diseases emerge, Phua said.

Covid-19 impact already worse than Sars, Singapore PM says

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, chief of the World Health Organisation (WHO), on February 20 praised Singapore’s efforts to leave no stone unturned when weeding out cases of the coronavirus, which causes the pneumonia-like Covid-19 disease.

Singapore’s health ministry has reported at least 90 cases of infection, with 53 of them discharged.

In a televised message on February 8, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said that experiencing the Sars epidemic had made the island nation “much better prepared” to deal with the virus this time around.

“We have expanded and upgraded our medical facilities … We have more advanced research capabilities to study the virus. We have more well-trained doctors and nurses to deal with the situation,” he said.

These points were also raised by health care and infectious diseases experts, who said the city state had geared up progressively since 2003.

Lisa Ng, senior principal investigator of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*Star)’s Singapore Immunology Network, said Sars had served as a “wake-up call” for the Lion City.

“For Singapore, the Sars experience was a wake-up call about how diseases know no borders. It can come anytime, anywhere,” she said, adding that Singapore was particularly vulnerable to such outbreaks given its openness and connectedness to the world.

Singapore PM: coronavirus spread could worsen but ‘no need to panic’

But from there, government agencies learned that maintaining a strong working relationship between scientists and the public health community was key, Ng said, adding that this dynamic has been “instrumental” in containing the current outbreak.

“Many of these relationships, and the current open exchange of information were strengthened during and after the Sars episode in 2003,” she said.

The other infectious diseases Singapore has experienced, including the Chikungunya fever outbreak in 2008 and the 2016 Zika virus epidemic, have helped bolster these relations, Ng said.

ACTION PLANS

She said the aim of infectious diseases scientists would typically be to get their work published in journals, but the rise of such viruses meant there was a “translational outcome” in their work.

Sebastian Maurer-Stroh, deputy executive director of A*Star’s bioinformatics institute, said Singapore’s current strategies have also evolved along the way.

“Preparedness plans that were made since the Sars episode of 2003 were taken out of the drawers and brought into action. Since then, plans have been further adapted after the emergence of pandemics such as Mers and Zika,” he said, referring to the Middle East respiratory syndrome. “Everything was very well set up to deal with a novel virus.”

Can Asian economies survive the coronavirus?

Maurer-Stroh said another key learning point from Sars was how agencies in Singapore worked together to respond to the outbreak.

“There is a good interplay between agencies, as the complementary puzzle pieces create the big picture needed to deal with complexities of an outbreak,” he added. “Coordination is also key and Singapore has just the critical size – not too big and not too small – where this can be done efficiently.”

Phua, the health economist, likened Singapore’s approach to dealing with Sars to a war scenario.

“It was all-out warfare, the enemy was Sars,” he said, adding that the the Covid-19 disease was now the new foe.

During the Sars epidemic, then-home affairs minister Wong Kan Seng had formed an interministerial committee to provide strategic directions, and likewise, a similar task force was formed this time around.

“You need a whole-of-government approach, with all agencies involved – which means it’s not just the health ministry, but also the foreign affairs ministry, the home affairs people, and the police force,” Phua said.

“You could say that in these times, it’s draconian, but in wartime and [during] an epidemic, it’s a very good response,” he said.

Asian countries anxious over virus, want China flight ban: new poll

Phua added that a leaf taken out of the Sars playbook was how leaders displayed good communication.

A daily press conference was held to give Singaporeans up-to-date information on the situation, and in the same way, the health ministry is now releasing timely details on new coronavirus cases, he said.

“The cost of the scare is worse than the disease itself, so it [is] important for our leaders to be rational and communicate well,” he said. “You have to be transparent to inform the masses.”

TRACING CASES

That said, Phua acknowledged it was easier for Singapore, with a population of 5.7 million, to adopt certain measures compared with a much larger country like China.

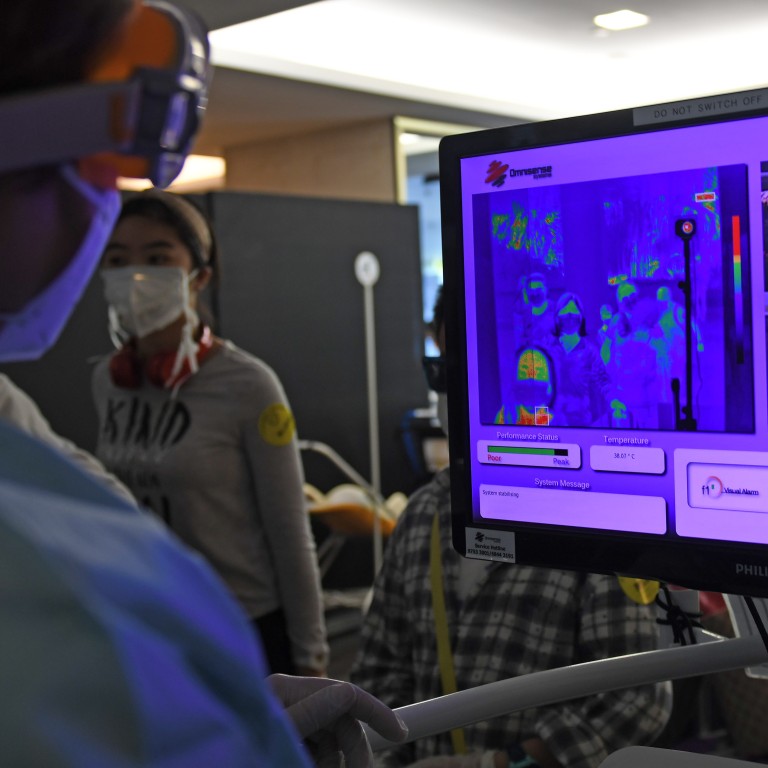

A recent study by Harvard University’s Centre for Communicable Disease Dynamics found that Singapore is identifying three times more cases than other countries due to its disease surveillance and contact-tracing capacity.

The city state’s contact-tracing operation, also adapted from the Sars playbook, starts in hospital, where infected patients are required to map out the activities they have done and the people they have been in contact with for two weeks, down to the minute, according to the health ministry’s Communicable Diseases Division.

Why did Singapore have more coronavirus cases than Hong Kong?

A dedicated team of workers would then call people up to check if they are “close contacts” of the coronavirus patients, defined as anyone who has been within two metres and spent 30 minutes with an infected patient.

In some cases, airlines would have to hand over flight manifests, and security cameras across the country would be used to further track patients’ movements.

This has enabled Singapore to ring-fence potential clusters of local transmission, where officials would weed out suspected cases and quarantine them.

On the clinical front, Singapore has gained some knowledge of coronavirus properties from the Sars outbreak, which has better equipped the country up to put up a better fight against the Covid-19 disease.

Phua said even though experts were still discovering certain properties of the novel coronavirus, there are common traits of coronaviruses that are already known.

For example, a coronavirus will generally burn itself out because it is an unstable virus, said Phua, adding that Sars burned itself out in eight months.

The next coronavirus: how a biotech boom is boosting Asian defences

Another key trait Phua highlighted was how coronaviruses are manufactured mostly in temperate countries, which means a temperature cooler than room temperature is needed to “maintain” the live virus.

“Once you reverse that concept, then you know how to destroy the live virus,” he said.

Phua cited how one of the measures Singapore adopted after learning the properties of coronaviruses was to stop air conditioners in the Tan Tock Seng Hospital, and install a suction system to suck the virus into a hot and humid environment.

“We also had outdoor waiting areas. Instead of having [potential patients] sit in enclosed air-conditioned rooms and pass germs, we took them outside,” Phua said.

CLOSER PARTNERSHIPS

On the research front, Ng from A*Star said Singapore has placed greater emphasis on a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach to researching infectious diseases since 2003.

Incorporating research areas such as genomics, molecular biology, data analytics and bioinformatics, the range of capabilities have built a “strong ecosystem” for Singapore to take on new viruses, she said.

Specialised institutions have also sprung up since Sars, including the National Centre for Infectious Diseases and the Duke-NUS Medical School.

How to beat the coronavirus? Re-creating it in Singapore, Australia is vital first step

“Importantly, several researchers based in Singapore have also established themselves internationally to be respected leaders in various aspects of infectious diseases research,” she said.

These top researchers include Wang Linfa, director of the Duke-NUS’ Emerging Infectious Diseases Programme – who was part of the Singapore team who cultured the Covid-19 disease from infected patients last month, in the first steps towards developing potential vaccines and cures.

“They are part of key international expert panels and committees that enable the dissemination of important information and influence,” Ng said. “These connections offer Singapore the agility to respond to diseases outbreaks quickly and efficiently.”

Apart from the strides the Lion City has made in the medical and research fields since the Sars outbreak, Prime Minister Lee said that Singapore is more psychologically prepared, too.

His speech came days after Singapore raised its epidemic alert level to orange – the same that would have been used for Sars in 2003, had the framework existed then.

The alert level indicates that while the nature of the disease is severe and can spread easily from person to person, it is being contained and has not spread widely.

Coronavirus fears spark questions about Singapore’s social resilience

After the alert level was raised, droves of citizens flocked to supermarkets to hoard essential supplies.

Lee stressed in his national address that the country was well-prepared to face the coronavirus outbreak and had sufficient food supplies, and some measure of calm returned the next day.

Lee said that the Sars experience had informed Singaporeans on what to expect and how to react.

“Most importantly, having overcome Sars once, we know that we can pull through this, too,” he said.