TCM diplomacy? Indians take to acupuncture, cupping therapy amid strained ties with China

- TCM techniques and Chinese herbal medicines increasingly used to treat various ailments, Indian medical professionals say

- As TCM grows in popularity among Indians, experts call for regulatory control to ensure patients receive correct treatment

“I lost all hope of standing on my feet but my condition improved drastically,” Kaur told This Week In Asia. “It’s nothing short of a miracle.”

An edge over China? India’s WHO-backed traditional medicine centre ‘a victory’

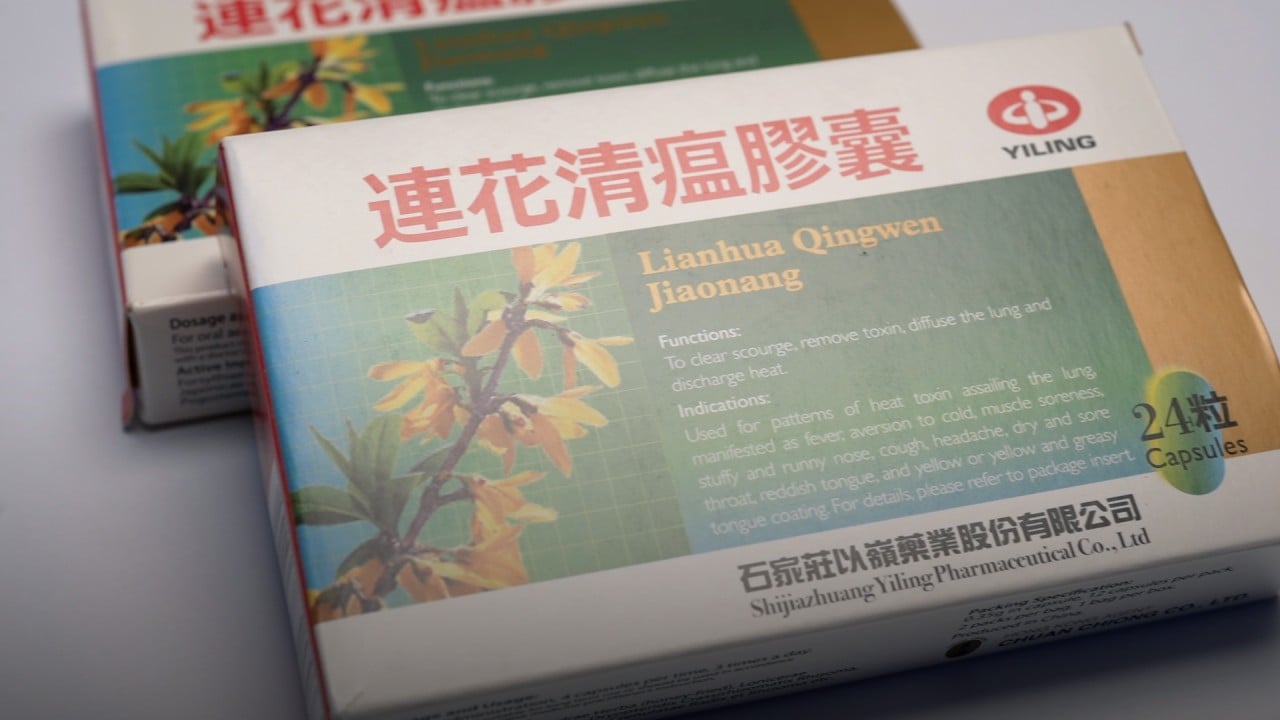

Indian medical and para medical practitioners say TCM techniques – including acupuncture, cupping therapy, moxibustion – and Chinese herbal medicines have been increasingly used to treat ailments such as orthopaedic pain, infertility, diabetes, cancer, psychosomatic disorder and drug addiction.

“TCM works where modern medicine fails,” Mumbai-based TCM practitioner Jasmine Modi said. “Earlier, patients complaining of arthritis, diabetes and asthma consulted me but now people want to be treated by TCM even for their minor headaches, coughs and colds.”

Indian e-commerce platforms and apps have also embraced the trend, selling Chinese herbal medicines and offering cupping therapy for home services. Several private institutes and international experts have been offering acupuncture courses in India as well.

TCM gains ground in India

Modi said TCM’s popularity was rising because people saw faster results from a more cost-effective treatment.

In India, for example, a single session of Botox treatment for facial contouring costs about 15,000 to 18,000 rupees (US$188-US$220), while TCM clinics charge 4,000 rupees (US$48) for the same service.

A patient who gets Botox also needs to repeat the routine every six months but the effects of TCM last for three years.

Modi’s youngest patient so far is an infant with jaundice, while the oldest was a 98-year-old suffering from paralysis.

Celebrity endorsement also worked in TCM’s favour, according to Delhi-based physiotherapist Nitish Kumar. For example, Sri Lankan actress Jacqueline Fernandez’s Instagram posts on her experience with cupping therapy – a technique in which suction cups are placed on the skin to improve energy flow and reduce muscle spasm – triggered interest in its use and benefits.

Kulveer Kaur, whose father and sister turned to TCM for treating their heart disorder and hearing problem at Delhi-based TCM specialist Jeewan Kumar Kaushal’s clinic, said that they knew that they were on the right path when they found that a popular Punjabi singer was being treated by the same doctor.

“My father never had to take allopathic medicines for his heart ailment and my sister’s hearing disability also recovered more than 80 per cent with TCM,” Kaur said.

“We felt reassured about this line of treatment when we saw celebrities coming for the same.”

At Kaushal’s clinic, patients suffering from nervous disorder, chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis, deafness and prostate cancer, queue up for treatment.

Kaushal completed a diploma in acupuncture and Chinese medicine at Hong Kong’s International Acupuncture Society. He counts politicians, bureaucrats and police officers among his clients.

Loved by India’s Modi, Cuba’s Castro, ‘wood’ you believe this miracle tree?

Kaushal, who treated Kaur, said he imported several herbs including ginseng, astragalus and goji berries from China easily before Covid-19 but had to switch to the north-eastern state of Sikkim and neighbouring Bhutan to source these herbs during the pandemic.

But Kumar and Kolkata-based physiotherapist Vikas Tarway warned that many quacks bought cheap cupping therapy kits online to use on patients.

“It’s important to know where to apply, how long to apply and on whom to apply,” said Tarway, a senior consultant at Kolkata’s Apollo Multispeciality Hospitals, who uses cupping therapy coupled with physiotherapeutic electrotherapy modalities and manual therapy, for better results.

“Patients may receive blisters if suction cups are applied on damaged skin for longer than 15 minutes. Similarly, one cannot apply them on cancer patients receiving chemotherapy as their skin is usually dry and thin.”

Kumar, who has been using cupping therapy for the past four years, said it should be regularised and the treatment taught in physiotherapy courses to save patients from quacks.

Recognising acupuncture

Inderjit Singh, who runs Dr DN Kotnis Health and Education Center in Punjab, recalled there was little acceptance of acupuncture in northern India when he started practising in 1975, due to Sino-Indian tensions following the 1962 war.

Acupuncture was introduced in West Bengal in 1959 by BK Basu, one of five Indian doctors who served in China during World War II. West Bengal became the first Indian state to recognise the treatment; five decades later in 2015, the western state of Maharashtra recognised courses on acupuncture, with a council later formed to register acupuncturists.

In 2019, the Indian government recognised acupuncture as an “independent system of healthcare”, but there was no initiative to promote and regulate it.

What’s driving India’s newfound obsession with saatvik food?

Some private institutes in other states run acupuncture courses but they are often not recognised. Indian specialists have to head to places such as China, Hong Kong and Sri Lanka to master the technique and train their colleagues upon their return. Some, like Mumbai-based therapist Siddique Shaikh, invite trainers from China, Malaysia and Germany to conduct courses on acupuncture, moxibustion and cupping.

Shaikh said acupuncture makes the visible recovery in paralysis patients possible in two months.

Singh urged the Indian government to capitalise on acupuncture’s growing popularity and introduce specialised courses, saying “millions of Indians will benefit if designated courses are taught in credible medical institutes”.

At a time of strained Sino-Indian ties, a tiny acupuncture needle could heal the “wounded relationship” between the two, Singh added.