As their ‘American dream’ sours, Koreans in the US eye a return home

- For decades, South Koreans have seen the US as a land of opportunity, but many who emigrated there are now returning to the country of their birth

- Rule changes around dual citizenship are one motivating factor, as is the cost of health care and the lack of a sense of community in the ‘land of the free’

On the surface, it was everything he had imagined. He had a house, his own business, and the opportunity to live in the “land of the free” – but even though he was living in California, with the largest Korean-American population of any US state, Seok began to feel homesick.

“I could go eat kimchi-jjigae or Korean barbecue whenever I wanted in one of the many Korean restaurants in my neighbourhood,” he said. “But, it just didn’t feel the same as eating back home in Korea.”

South Korean youth turn on China as Hong Kong, Covid-19 weigh on minds

Another factor weighing on the minds of the couple, who were approaching their sixties by this time, was health care.

“In the US, we needed to buy a surplus of medicine to store in our house in case of emergency. But in South Korea, it’s easy to visit a hospital even during the middle of the night,” Seok said. “Plus, Korean health services are a fraction of the cost of a hospital visit in the US.”

So, in 2018, the couple sold their house and decided to move back to South Korea, while retaining their American citizenship. To ease the transition, they bought an apartment in Songdo American Town – a US$500 million housing project in the port city of Incheon that aims to help Korean-Americans resettle in their home country.

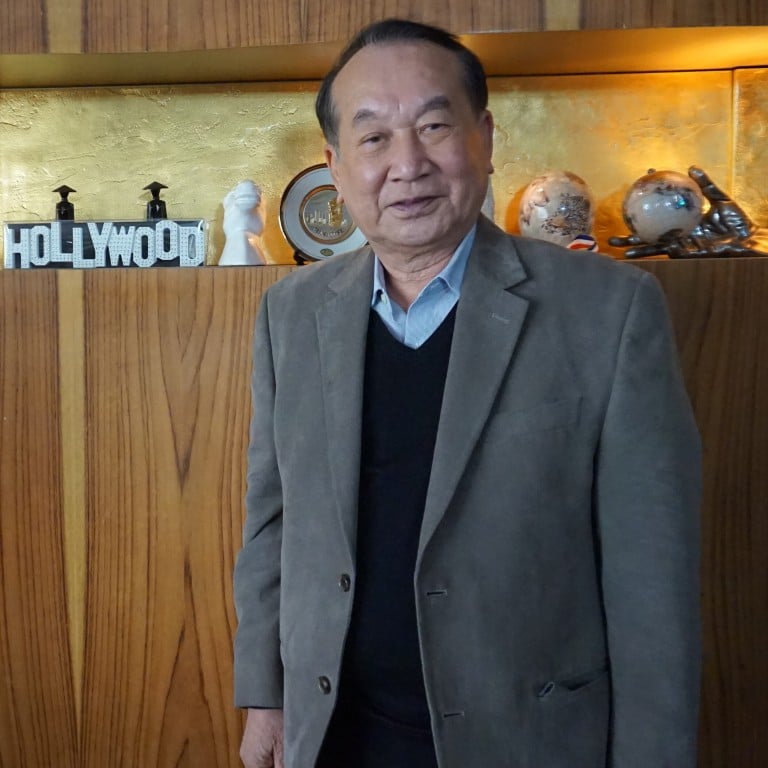

It is the brainchild of Kim Dong-ok, a former reporter and radio host who returned to South Korea in 2012 after living in the US for 50 years and founded KOAM International – short for Korean-American.

“After spending most of my life in the US, I knew I wanted to go back to Korea for retirement,” Kim said. “And I knew that many fellow Korean-Americans who spent a good part of their lives in the US also had similar plans to move back to Korea.”

All 830 flats that Kim’s company delivered in phase one of the project have now sold out, so work has begun on 500 more as part of a US$600 million phase two expansion to the town. A phase three is also in the works thanks to the amount of interest in the project.

It’s become better to live in South Korea rather than America.

“When you grow old in the US, you go to a nursing home – but here, there are so many things to do with your family and friends,” he said, adding that public transport links in much of Korea were better than those in the US and “it’s become better to live in South Korea rather than America”.

The allure of the “American dream” for many Koreans is not as strong as it was once, according to Yoon In-jin, a sociology professor at Korea University and a past president of the Association for the Studies of Koreans Abroad.

“Korea was economically dependent on America and American soldiers stationed in Korea introduced their culture to the Korean people, so the two countries began to possess a particularly strong relationship while Koreans expressed a lot of interest in America,” he said. “This resulted in educated Koreans in the higher classes migrating to America en masse in the sixties and seventies to live under better conditions.”

Yoon pinpoints the 1988 Seoul Olympics as the moment that trend began to change, after which “immigration to the US fell drastically”, he said, “to the point where only 20,000 or less make the move to the US per year”. At its peak in 1976, more than 30,000 Koreans emigrated to the US.

According to US State Department figures, the number of Koreans receiving immigration visas fell from 15,895 in 2009 to 12,710 in 2017. Despite this, the US is still host to more ethnic Koreans than any other country apart from China and is the top destination for overseas Korean students.

“Koreans who immigrated in the 1970s now want to spend their retirement in Korea,” said Yoon, who added that a law change in 2011 means Korean-Americans over the age of 65 can now hold dual citizenship, which they could not previously.

US urges Japan and South Korea to speak out against China

Not all of those choosing to return left of their own free will, either. Cory Lemke is one of the estimated 200,000 Korean children adopted over the past six decades into families in more than 15 countries – though many went to live in the US.

International adoption of Korean children began as a result of the large number of orphans resulting from the Korean war after 1953 and peaked during the 1980s and 1990s.

Lemke, who grew up in Iowa, returned to South Korea in 2013 to reconnect with his birth parents after quitting his marketing job in the US. He is among an estimated 350 adoptees who currently live in South Korea after moving from the US.

Having gone through multiple jobs in the southwestern city of Daegu, cultural differences and the social hierarchy that exists in South Korea’s workplaces began to chafe.

“One time, I was scolded pretty bad by my boss for not attending a family funeral,” he said. “I had never even heard of the person.”

Other social gestures like standing up and bowing to the boss also made the transition difficult.

“I know many Korean-Americans who were pushed out of their jobs or even left the country due to the cultural differences,” Lemke said. “And it was always the women who were the first to leave as it’s probably easier for men to live in a society that is male-dominated.”

‘Go home’: the hidden struggles of South Korea’s naturalised basketball players

Yet he has continued to live in South Korea for the past seven years, and thinks the trend of Korean-Americans returning home will continue.

“On top of the Korean government making it easier for Koreans with American citizenship to make the move to Korea, the economic and social opportunities added with the certain level of social prestige of being Korean-American can be a strong pull for many to come here,” he said. “This is especially true for Korean-American men who face racism and find it hard to find a partner to settle down with in the US.”

Yoon, the sociology professor, said “Many left South Korea, through one way or another, when it was going through its toughest times. But, now, things are looking good and people are coming back to start a new dream.”