Opinion | India’s women must hold politicians to their promises in this election – their power at the ballot box is rising

- The major parties have gone to great lengths to woo the nation’s women with promises of a grand female future, but similar pledges in the past have fallen flat

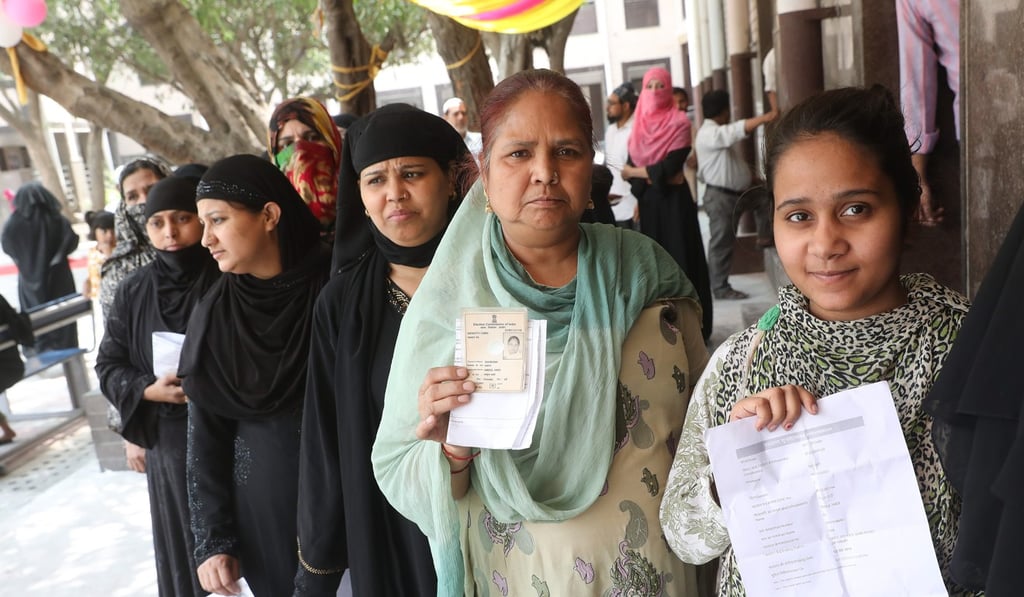

As India votes in general elections, its parties are keeping a close eye on the role women will play. When both the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and opposition Indian National Congress (INC) released their election manifestos, it was clear the power of the female voting bloc was finally being taken seriously. For starters, they both promised a parliament that would be 33 per cent women.

This group could be the key to winning this election. In 2014, some 16 of India’s 29 states saw an increase in female turnout, bringing the nationwide figure to 65 per cent, compared to 67 per cent for men. That number is only expected to rise further this time around.

Women are under-represented in India’s political landscape not just because of these factors; rather, it is because gender roles run so deep within the veins of Indian society. This underrepresentation will need years of conscious effort and open doors to erase. Even at panchayat (village) level, where a 33 per cent quota for women applies, the ‘sarpanch pati’ – the panchayat leader’s husband – controls the politics of the area. A bill was passed by India’s upper house back in 2010, but the lower house is still yet to follow suit despite members of both parties openly supporting the quota.

One cannot help but be sceptical of these promises from the BJP and INC given both only had women on 8 per cent and 12 per cent of their tickets in the last election, respectively. The 33 per cent parliamentary quota was also in their 2014 manifestos.