Coronavirus: to Chinese democracy what Chernobyl was to glasnost?

- The 2003 Sars crisis changed Beijing’s view on openness in governance and the timely release of information about health crises

- But China’s increasing move towards authoritarian rule under Xi Jinping makes the country even more vulnerable to the outbreak of epidemics

China has changed a great deal since then, at least in terms of economic development. In 2003, it was a low-income country, with per capita income of US$1,293; last year, that figure reached the benchmark of US$10,000, allowing it to join the middle-income rank. This refers to countries with per capita income of between US$3,956 and US$12,235, according to the World Bank.

Correspondingly, China has also made considerable progress in the development of medical science and public health services. Therefore, it would be logical for China to be able to do a better job in coping with epidemics now, as it has abundant resources at its disposal compared with two decades ago, not to mention the experience it gained in 2003.

Six ways the coronavirus crisis will change China’s relations with the world

However, the coronavirus has revived uncomfortable memories of Sars – including the repetition of mistakes that might have facilitated rather than contained its spread. Due to political reasons, China’s governance – including its management of public health crises – remains little changed since 2003, despite a short-lived improvement after Sars. The two viruses share 80 per cent of their genome, but the similarities don’t end there.

First, both outbreaks are believed to be associated with markets selling meat from wild animals. The Sars virus originated in bats and then spread to civet cats – a wild animal considered a delicacy in parts of south China – in a wet market in the southern city of Fushan, before it spread to humans. The new coronavirus is believed to have spread from bats to snakes to humans in a market in the central Chinese city of Wuhan. In both markets, wild animals were for sale. In the aftermath of Sars, the government banned the slaughter and consumption of civet cats. But obviously it failed to do enough to supervise the wild animal markets, despite repeated warnings from scientists.

Forget Sars, the new coronavirus threatens a meltdown in China’s economy

Official statistics suggest China’s investment in this area has been insufficient. In 2016, per capita health-care spending in China was just under US$400, compared with almost US$10,000 in the United States, according to the World Bank. China’s health-care spending accounted for just 4.9 per cent of its gross domestic product in 2017, compared with 17 per cent in the US and Switzerland’s 12 per cent. China has 1.8 practising doctors per 1,000 citizens, compared with 2.6 for the US and 4.3 for Sweden, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. That is why China’s hospitals are known for a shortage of doctors, overcrowding, long queues, corruption, distrust between doctors and patients, and violence.

Third, China’s failure to cope with the outbreak has exposed its shortcomings in public health management. The epidemic surveillance systems failed to sound an early warning and officials were also obviously ignorant about any such warnings, as both the government and the public were unprepared.

In the week before Beijing’s declaration of all-out war against the epidemic on January 23, life was normal in Wuhan with large-scale public gatherings and activities, even when hospitals in the city were crowded with patients showing symptoms.

The irony is that when a large number of people in Hong Kong wore face masks on the streets, there were few in Wuhan who did so. The severe shortage of medical materials including test kits and surgical masks suggested China had little in the way of emergency supplies. There was also obviously no contingency plan in Hubei province, or elsewhere in the country.

The coronavirus threatens the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on power

Fourth, China repeated its mistake in delaying the release of critical information about the epidemic – which may have been the result of a cover-up by local officials – allowing the virus to spread freely in the early stages and led to the loss of the best opportunity to keep the virus at bay. As with Sars, Beijing was widely accused of hiding critical information.

This official silence turned a localised health scare into a worldwide problem as it allowed the exodus of some 5 million people from Wuhan in the weeks before the city was locked down for quarantine purposes on January 23. During Sars, the rush to Hong Kong for treatment by an infected Guangzhou doctor had the same effect, as it exported the virus to the special administrative region before it spread worldwide.

Many believe Sars changed the Chinese government’s view of transparency in governance and the timely release of information about epidemics. Beijing did make some progress in terms of developing an epidemic surveillance, reporting, planning and management system, under the International Health Regulations. From the end of 2003 until 2006, the central government spent 25.7 billion yuan (US$3.7 billion) on upgrading facilities for public health emergencies and hospitals for infectious diseases. Beijing has since established the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention, which links hospitals nationwide and reports outbreaks in real time.

However, the dwindling of Sars’ legacy has been a major political setback in recent years, as China moves towards increasing authoritarian rule under the stewardship of President Xi Jinping. Xi, who ordered the nationwide fight against the new outbreak –calling it “a major test of China’s system and capacity for governance” – has tried to tighten the party’s control on every aspect of society since he came to office in 2012, which some critics say has reversed the post-Sars liberalisation.

In the same way the Chernobyl disaster helped trigger glasnost (or increased transparency) in the Soviet Union, many hope the coronavirus will provide, even more than Sars, the impetus for democratic reform to overhaul China’s increasingly repressive system – which makes the country more susceptible and vulnerable to the outbreak of epidemics. The best illustration of this is former Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s remark that Chernobyl, more than anything else, made absolutely clear how important it was to continue the policy of glasnost. ■■

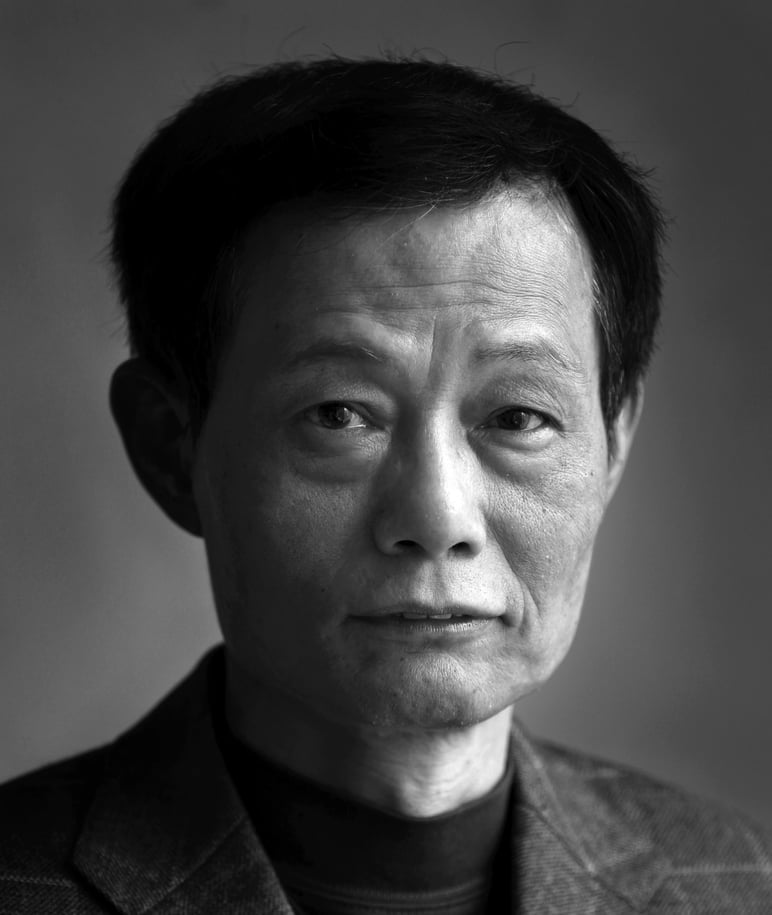

Cary Huang is a veteran China affairs columnist, having written on the topic since the early 1990s

Purchase the China AI Report 2020 brought to you by SCMP Research and enjoy a 20% discount (original price US$400). This 60-page all new intelligence report gives you first-hand insights and analysis into the latest industry developments and intelligence about China AI. Get exclusive access to our webinars for continuous learning, and interact with China AI executives in live Q&A. Offer valid until 31 March 2020.