Advertisement

Abacus | Is Tiger-cub Bill Hwang’s mauling an omen of a financial crisis for Hong Kong?

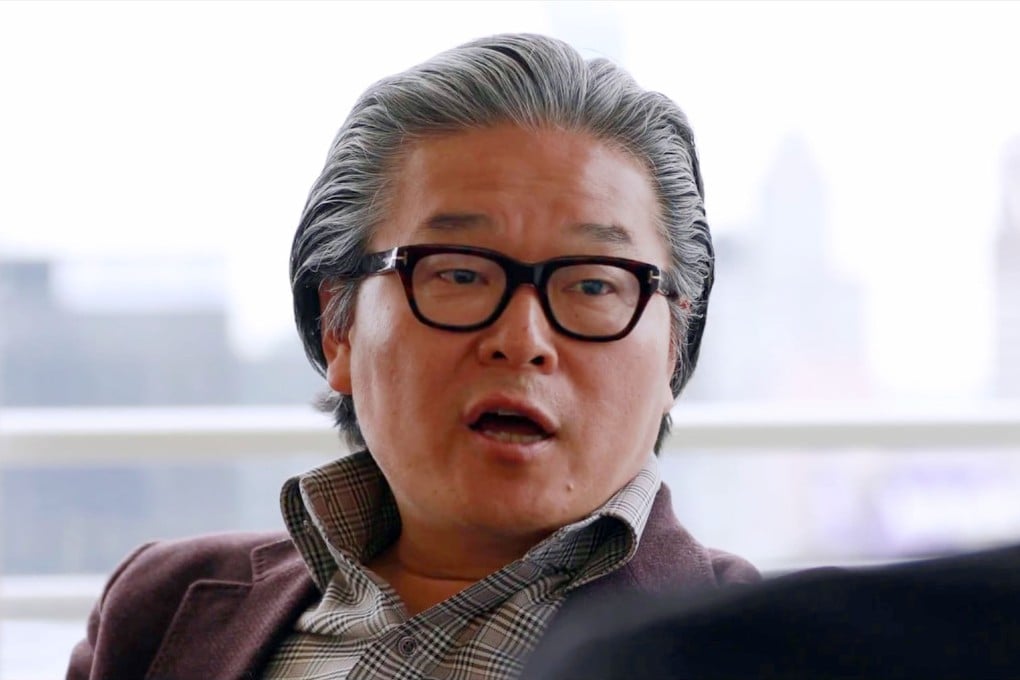

- Former Tiger Bill Hwang turned his multibillion-dollar personal fortune into catfood in a matter of days, inflicting nasty bite wounds on Wall Street

- In revealing his concentrated portfolio, regulators may have spotted a Lehman-shaped iceberg that will hasten the exit of Chinese securities from the US

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

5

THE WONDERFUL THING ABOUT TIGGERS

Having never been a mega wealthy hedge fund manager, what motivates their excessive risk-taking to become mega-mega wealthy is all Greek to me. So, when Archegos Capital Management blew up in March, as billionaire Bill Hwang wiped out his entire fortune leaving Wall Street to clean billions of dollars of nest-egg off their faces, I really could not believe what had just happened. And Archegos Capital wasn’t even a hedge fund.

Over a thin, crispy pizza, Peter, an old friend and colleague who is far smarter than me, asked if I had looked deeply into the Archegos story. I must admit, I had not and just rolled my eyes like everyone else at the ludicrous position Wall Street had put itself in again. But Peter’s point was that Archegos was loaded up with investments in Chinese companies that have been accused of fraud. This triggered a memory of watching a documentary called The China Hustle and raised the question: is this the conclusion to its unfinished story, which implied another financial crisis was in the making? And if so, are we about to be hit again?

Advertisement

But first, a little background. Bill Hwang was a product of Tiger Management, one of the largest hedge funds in New York in the late 1990s and one of the highest commission paying clients any broker could wish for.

Unfortunately, Hwang went bad and pleaded guilty to insider trading of Chinese bank stocks in 2012. Both he and Tiger Asia were charged separately and the defendants settled with a US$44 million fine. Hwang bounced off with his US$10 billion fortune to create his “family office” called Archegos, and a four-year ban from trading in Hong Kong tagged along with him.

There it sat, a delicately balanced bomb; as long as there wasn’t a big shock to share prices it wouldn’t go off

HONEY HUNT

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x