Advertisement

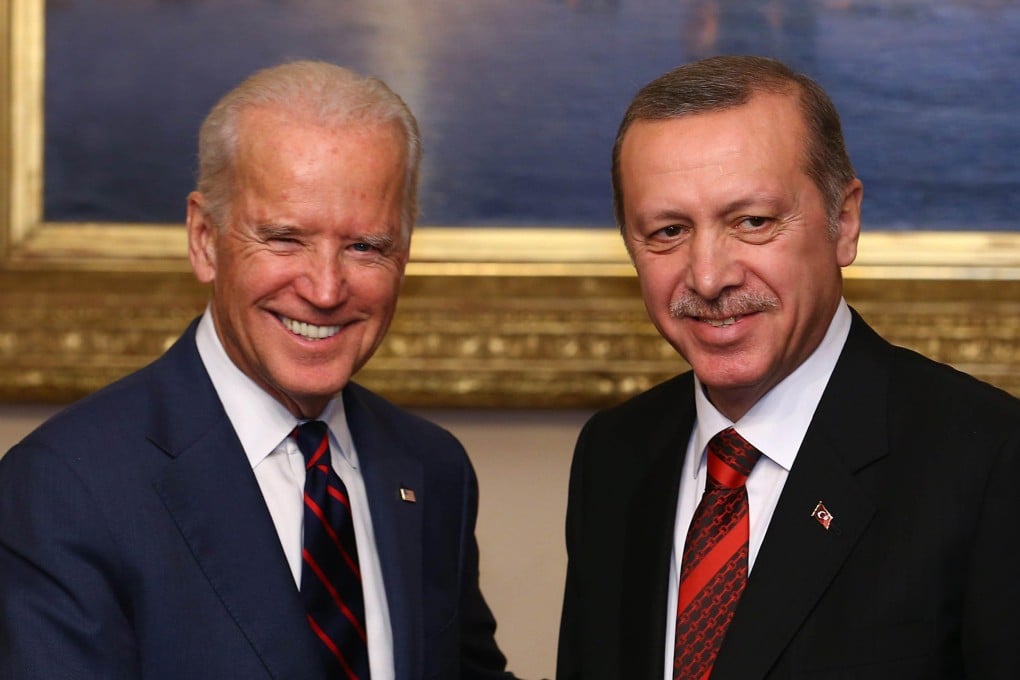

Opinion | The real test of US power may be when Biden meets Erdogan, not Putin

- All eyes are on the meeting of the US president and his Russian counterpart, but it is his date with the Turkish leader that could telegraph the American approach to conflicts overseas for the next four years

- Turkey’s flexible foreign policy when it comes to China and Russia is worrisome to the US as it seeks to rebuild alliances and reassert its global influence

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

2

Next week promises to be a red-letter one for diplomacy and alliances. The summit between US President Joe Biden and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin has hogged all the headlines, but while it has not received top billing, a meeting on June 14 will be equally important.

That is when Biden will meet Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the first step in an attempt at repairing ties between two Nato members that currently lie in tatters. It could also telegraph the American approach to the Middle East and beyond over the next four years.

Turkey has been a thorn in the side of the United States and other Nato members for some time now, a result of its assertive repositioning as a key actor in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, and the Caucasus regions.

Advertisement

Ankara has confronted Greece in the Mediterranean Sea, increased its presence in Kabul ahead of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, and openly contested the US support of the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) in Syria.

At the top of this list of frictions between both sides is Turkey’s acquisition of the Russian S-400 missile air defence system.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x