If South Korea is beating the coronavirus, why are so many of its people staying home?

- South Koreans are staying away from offices, schools and places of worship despite infections falling

- Experts say Covid-19 has woken people up to new ways of working and many are now loathe to go back

02:26

Can South Korea resume normal life after its coronavirus peak?

Statistics show that despite the country being one of the safest places in the world to venture outside, many South Koreans remain averse to returning to workplaces, schools and places of worship, prompting some experts to suggest Covid-19 may have sparked a long-term change in behaviour as a famously hard-working nation begins to rethink its ideas of workplace etiquette. Given South Korea is ahead of the curve in its fight against the virus, such trends could give a valuable insight into what might be in store for other nations as their own infection levels fall.

FOR WORKAHOLICS, A MOMENT OF CLARITY

South Korea is a notoriously hard-working nation. An OECD study in 2016 found South Koreans worked longer hours than citizens of any other developed country: an average of 2,069 hours per year, per worker.

Lee Myung-ho, a researcher at the Yeosijae think tank based in Seoul, believes that widespread work-from-home policies brought in during the height of the outbreak have helped a “workaholic country” wake up to the nature of its addiction.

Lee points out that before the outbreak of the virus, less than one per cent of employees had experienced working away from the office.

But this number had risen to more than 60 per cent by April, according to a survey by the human resource development website Hunet, which also found that more than 80 per cent of workers would choose to do so again if given the chance.

Anti-vax movement threatens Asia’s coronavirus recovery

Significantly, it is not only major firms like Samsung and SK Telecom that have implemented work-from-home policies since the height of the outbreak in February; small and medium-sized firms have done the same in return for funding from the Ministry of Employment and Labour. From the end of February to the end of May, 4,366 small and medium-sized businesses received the funding, allowing a total of 47,435 employees to work either flexible hours or from home.

This is a once unthinkable situation, Lee points out.

“Due to the culture of Korean workplaces where office hierarchy is strict and workers are expected to act like they are working hard in front of their bosses, working away from the office and the supervision of seniors have long been considered against workplace etiquette,” says Lee.

Having had a taste of what was once a forbidden fruit, workers are now loathe to give it up, believes Lee.

“People are starting to realise that most work and tasks are possible even in the comfort of one’s home.”

THE HOME ADVANTAGE

One of the biggest advantages of working at home is time. The average Korean commutes for one hour and 14 minutes each way, according to a survey by Dalia Research in 2017.

Kim Sun-bae, 45, saves three hours every day by not having to report to his office in the IT district of Bundang, just south of Seoul. The engineer of a major internet service corporation and father of three has been allowed to work from home all five days a week.

“My company has been lenient with employees, especially for people with underlying diseases or women who are expecting,” he says.

“I’m pretty split between wanting to go back to work and staying at home.”

While he misses the large office space, he has become accustomed to the comforts of home and the time he saves on commuting he can spend with family, or on daytime naps.

“Another big change is that we don’t need to stress over having face-to-face meetings for every task that is handed out by our seniors,” says Kim.

FEARS FOR THE LITTLE ONES

Kim is not the only member in his family going through a transition. His children have now returned to school after almost five months at home.

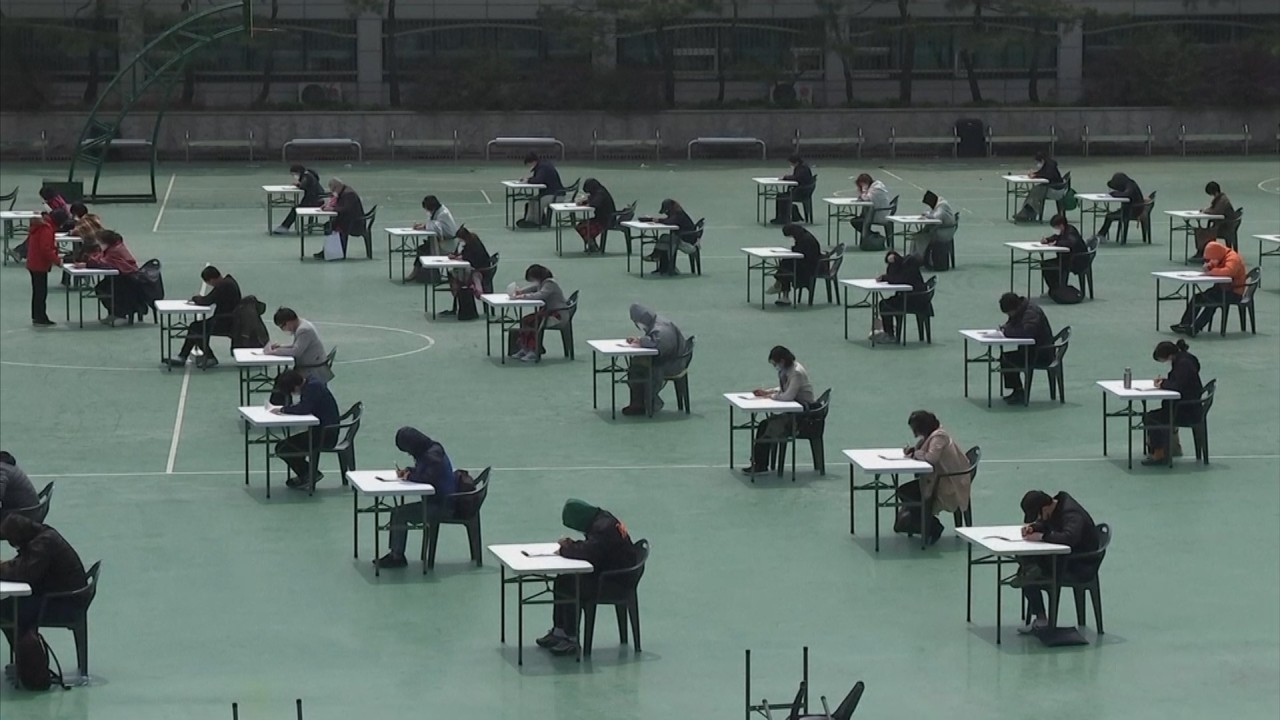

High school seniors were the first to return to classrooms, on May 20, and other grades have followed suit in a staggered fashion. By Monday, all grades were supposed to have returned. However, on Thursday, 511 schools either stopped or delayed the resumption of classes due to an increase in the number of infections. According to the Ministry of Education, on May 26 and 27, some 257,093 students did not report to classrooms. For now, the ministry has no plans to punish them.

“There’s a popular saying among parents that school classrooms are like Shincheonji cult churches and hallways like the clubs of Itaewon,” says Kim, referring to recent Covid-19 clusters.

As for Sunday school, Kim does not plan to send any of his children when his church resumes physical services this weekend.

SHOPPING IS ONLINE

Adding to the lure of staying at home are the many advances made in online shopping.

Even before the pandemic, contactless consumption in services such as food delivery grew nearly five times from 6.7 billion won (US$5.6million) in 2017 to 35.9 billion won by 2019, according to the credit card transaction data from Hyundai Card.

Sales of online video content leapt ninefold over the past two years, with the use of Netflix increasing 20 per cent in March compared to the previous three months according to credit card data from Shinhan Card. During the same period of time, ticket purchases to live stage performances and movies dropped by 65 per cent.

00:59

South Koreans social distance at drive-in K-pop concert

EVEN GOD IS ONLINE

Lee Eun-bi, 25, is one of the many worshippers who has missed the live services at her church in Paju, north of Seoul, and turned to online services to fill the hole in the interim.

However, when her church opened back up she found she had enjoyed the online services so much she no longer wanted to return to the physical church.

Chinese tourists, travel bubbles: how Asia can refloat travel industry

“Online church is comfortable because I don’t have to move too much on a weekend to attend service,” she says.

A survey of 412 churches by the Christianity Media Forum of Korea found that church attendance on the first weekend of May was just 20 per cent of the pre-pandemic level.

With the coronavirus on the back foot, but not yet completely defeated, worshippers like Lee also feel less guilty about missing a service.

“There’s also the fact that I have a pretty legitimate case now for not going to church during my day off,” she says.