Philippine election: why is front runner Bongbong Marcos Jnr so hands-off, wary of debates and pressing the public’s flesh?

- Son of murderous late dictator avoiding media interviews and taking opponents on, while recent viral video showed him recoiling at a fan’s touch

- Experts say his team want to avoid jeopardising comfortable lead, assisted by his wealthy family’s well-oiled online disinformation campaign

With only two months left before the May 9 presidential elections, the candidate leading the polls continues to avoid debating his opponents and doing hard interviews with the press.

On February 27, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jnr, 64, refused to join nine other presidential candidates in a debate sponsored by CNN Philippines. He said he had a “busy schedule”.

On January 22 he was a no-show in a three-hour interview featuring four other candidates with the GMA Network TV station. Marcos’ spokesman Vic Rodriguez claimed the interview would have been “biased” against his client.

Who’s who in Philippine presidential election, and their China policies

Announcing that the Commission on Elections (Comelec) will host a presidential debate on March 17, spokesman James Jimenez said it was “important that candidates take the opportunity to speak to the public, to present their plans for government”.

Earlier he said a candidate’s refusal to attend a debate “could be a red flag for the voters”.

What is unfolding seems to be part of a deliberate policy where Marcos will do nothing to endanger his high popularity numbers. Polls taken in January show he has a comfortable lead: a Pulse Asia Research survey reported 60 per cent of respondents would vote for Marcos for president, and only 16 per cent – a distant second – would choose his closest opponent, current Vice-President Leni Robredo.

Political strategist Alan German, president of Agents International Public Relations, said Marcos’ ratings are high because of the disinformation the Marcos family have spread on vast online networks.

“They’ve been at it a long time, they’ve had the advantage of time. They’ve been propagating their very well oiled social media machinery.”

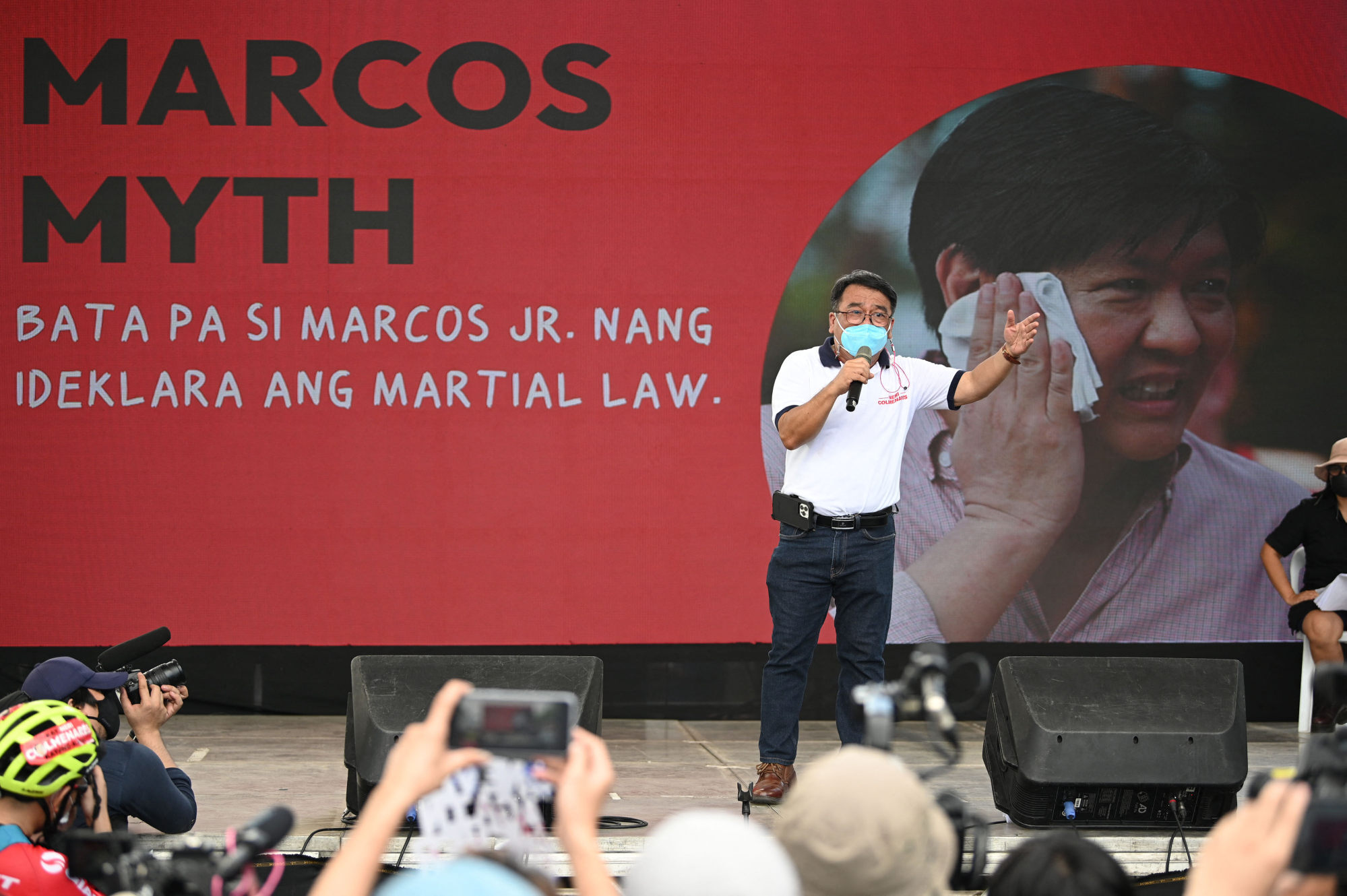

The main issue with Marcos junior is that he is the only son and namesake of the brutal dictator whose 14-year martial law regime tortured and murdered thousands of Filipinos.

Bongbong himself is a convicted tax evader who has also managed to avoid being jailed. He, his mother and his sisters cannot travel to the US where they risk being immediately arrested for defying a US court judgment to pay billions of dollars to victims of human rights abuses.

He denies anything bad happened during his father’s regime, denies that his family plundered the treasury and continues to block attempts by the government to recover still frozen accounts abroad. In the 1990s he sneered that his father’s human rights victims who claimed compensation were only after money, describing them as “victims of their own greed”.

It is one reason Marcos avoids debates and hard interviews: he knows his family’s sordid record will be brought up. This happened in 2016 when he ran for vice-president (ultimately losing to Robredo) and joined a debate.

Philippines ‘Bongbong’ tax evasion accusations dismissed

Not only was his family’s record on human rights, corruption and ill-gotten wealth pointed out by the other candidates, but Marcos made a fool of himself.

Candidates were given thumbs-up and thumbs-down signs and asked to hold them to express a stance. When asked if he ever engaged in corrupt practices, he initially held his thumbs up-sign, changing to the thumbs-down sign after realising his mistake, leading to laughter and booing from the audience.

This all helps to explain why “avoidance” best describes the current Marcos strategy. Not only has he shied away from debates and hard interviews, but he has even occasionally shunned his own followers.

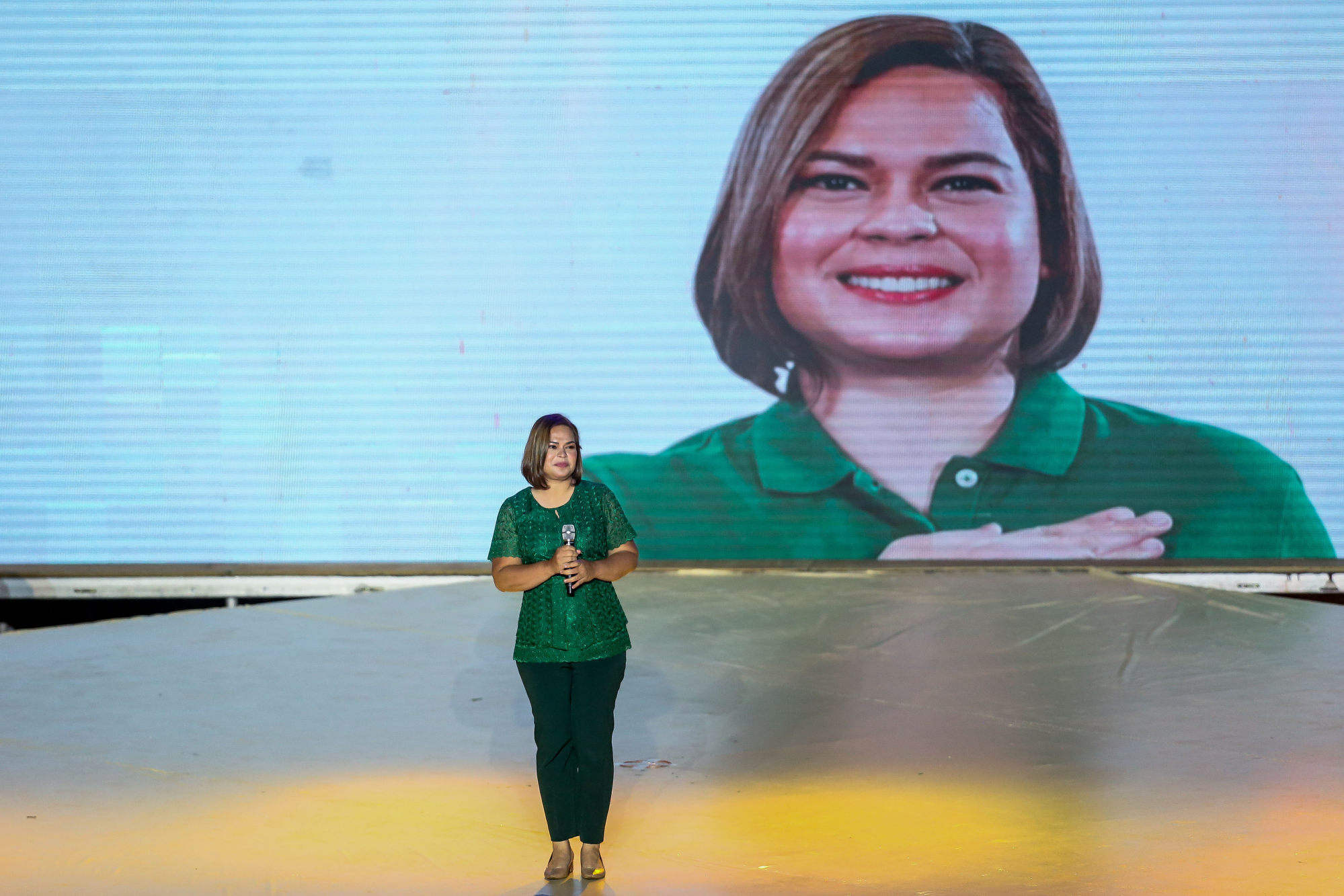

Two weeks ago Marcos did the unthinkable: while on a campaign sortie standing inside a truck inching its way through a crowd of supporters, he visibly recoiled when a fan on the street reached up to clasp his right hand. He jerked it away and then turned his back as if disgusted. A video of the incident went viral.

His managers tried to spin the story by saying he had been accidentally touched on a hand that had a wound but the photograph they showed was of an injury in Marcos’ left hand. What he had actually jerked away was the right one.

Another video from an earlier sortie in one province showed him wincing and grimacing in apparent distaste as a grandmother grabbed him and kissed him on the cheek. The body language he showed is best described by the Tagalog word “nandidiri” – repulsed.

Marcos’ behaviour is unusual in a political culture where, during election campaigns, candidates can barely be restrained from wading into crowds, pressing flesh, barging into houses and kissing babies.

For his part, Marcos talks about how he will provide “unifying leadership” but does not give details. And his short, generic speeches, geared towards creating memorable sound bites, have been known to disastrously backfire.

In a March 2 tweet, former chief justice Meilou Sereno described the Marcos campaign messaging as “feel good” and that it aimed to “form an alternative universe in the minds of those who are convinced to believe in their unity theme”. But she said the alternative universe was “empty”.

Compared to his father, Marcos Jnr is a lightweight. The late dictator graduated with a law degree from the elite University of the Philippines, had one of the highest scores in the bar exam, was a master of law and practical politics, exuded charisma and spoke eloquently.

Bongbong does not have a degree although he lied about it a few years ago, claiming he got one from Britain’s Oxford University in the 1970s. Plus, being a convicted tax cheat is something critics say should disqualify him outright from running for political office.

“He was convicted of tax evasion in 1995. It carried the penalty of perpetual disqualification from running in and holding any public post,” said Perci Cendaña from the left-wing Akbayan Partylist.

Although Bongbong pales in comparison to his father, he has one thing his old man never had: the internet.

For years the Marcos family has industriously created vast networks of disinformation on Facebook and YouTube, rewriting history and sanitising the clan’s image, turning the brutal dictatorship into a “golden age”.

A simple search using “Ferdinand Marcos” on any of these networks will immediately cough up dozens of pages extolling the tyrant’s virtues. There are too-good-to-be-true tales of gold and treasure that the Marcoses say they will share if Bongbong wins.

Political strategist German said the family was “reinventing their own history, their own myths and just really tying it to a message of return to a glorious age of prosperity, it’s all a promise of utopia”, adding that Filipinos “are suckers for that”.

Philippines’ Pacquiao vows to chase Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth

He said he did not want to sound like an “intellectual snob” but it was apparent in past elections that people in the Philippines “really go” for what are basically empty promises.

Victor Andres Manhit, managing director of the think tank Stratbase Group, noted how the internet and social media – mainly Facebook – are now a major source of information for voters.

In a recent forum, he said the group commissioned a survey to ask respondents about the presidential candidates and characteristics they were looking for and were “surprised” by the results.

Philippines’ Marcos Jnr wants military presence to ‘defend’ South China Sea

It’s easy for any candidate to say they will not engage in any negative campaigning but if you have a thousand online trolls to do it for you, you don’t need to personally do the dirty work

The respondents assigned more positive characteristics to Marcos than they did to other candidates. “Marcos has concern for the poor, compared to Pacquiao and Moreno, who came from poverty. Marcos is most honest and trustworthy, compared to Robredo. Marcos is not corrupt, compared to everyone.”

According to German, what is happening is “really the weaponisation of the internet on social media”.

He said that thanks to social media, Marcos Jnr can afford to strike a pose of aloofness and calm and not lash out at his opponents.

“It’s easy for any candidate to say they will not engage in any negative campaigning but if you have a thousand online trolls to do it for you, you don’t need to personally do the dirty work.”

‘Fake news’: Philippines blasts European Parliament in human rights row

The political strategist said the Marcos campaign dynamic was “very very strange, I would even say never seen before: he is leveraging his father’s achievements, yet you cannot criticise him for his father’s faults. When criticism is thrown at him for the abuses and corruption of the Marcos years, suddenly the narrative becomes, but oh, you cannot fault the son for the sins of the father”.

Asked what Marcos’ opponents could do, German said: “The really unfortunate psychology of the Filipino is that we value machismo. So if I were to strategise? This is a guy who is scared of debates. I would definitely bash that myth of his machismo.”

German added that Marcos’ opponents should target the so-called soft voters. “These are the ones who are being swept up by the hype, the so-called bandwagoners.” He said that, “unscientifically, I’m hoping the number is anywhere from 10 per cent to 12 per cent.”

Finally, he said, “on a very practical level, just use a lot of celebrity endorsers. The time is right to bring out the celebrities”.