Will a YouTube video about ‘being gay in Indonesia’ lead to an anti-LGBT law?

- A shock jock invited TikTok star Ragil Mahardika and his husband to talk about their married life on his YouTube show, sparking backlash from both conservatives and LGBT groups

- Activists say their fight for acceptance has been rolled back following the saga, with the community facing added persecution after an official proposed to outlaw homosexuality

Deddy Corbuzier’s “Close The Door” chat show often courts controversy by featuring celebrities and politicians to speak on sensitive issues, and the May 7 episode guest-starring Indonesian TikTok influencer Ragil Mahardika and his German husband Frederik Vollert was no different.

But the podcast – provocatively titled “Tutorial On Being Gay in Indonesia” – appeared a step too far for many in Indonesia, where sexual minorities are generally not accepted and have few rights. It was instantly condemned by religious conservatives, while LGBT groups were also critical of Corbuzier’s bid to exploit their plight to seek attention.

Three days after the webisode went live, Corbuzier deleted it from YouTube and apologised, saying he did not support LGBT rights. By then, it had garnered some 3 million views and 87,000 negative comments, mostly directed at the couple.

Ragil returned to Germany with his husband amid the backlash. His TikTok profile became suspended after thousands of Indonesians reported his account over the perception he had attempted to promote marriage equality in the Southeast Asian country.

Uphill fight

Those in the gay community say the talk show has not just taken their fight for acceptance backwards, but created a perception that Indonesia’s rainbow community has the same demands as those in other countries.

“The title alone was designed as a clickbait. The creator of the content was obviously only interested in ratings, rather than educating the public about what it’s like being gay in Indonesia,” said Muhammad Reza Pahlevi, 38, an openly gay Jakarta resident.

Exorcisms, ‘corrective’ rape: inside Indonesia’s LGBT ‘conversion’ therapies

“It’s a mistake to equate the needs of Indonesia’s LGBT community with their counterparts in Western countries,” said Hartoyo, an LGBT activist at SuaraKita (Our Voice). “As an LGBT rights advocate working in Indonesia, I know that there is no support for marriage equality here and it’s not even on the agenda for us.”

The most pressing need for Indonesia’s LGBT community was greater social acceptance, he said. On this front, Hartoyo believed Ragil had done the community a disservice.

“I believe Ragil meant well, but I can’t help feeling that he should have talked to us local activists, to ask us if it was something that could have helped foster greater tolerance for LGBT people,” he said.

Noting Ragil was able to flee the country after the controversy, Hartoyo added: “I don’t want to sound churlish, but now that Ragil has gone back to Germany, where his rights as a gay man are safeguarded by law, we are left to deal with the fallout from his interview.”

More persecution?

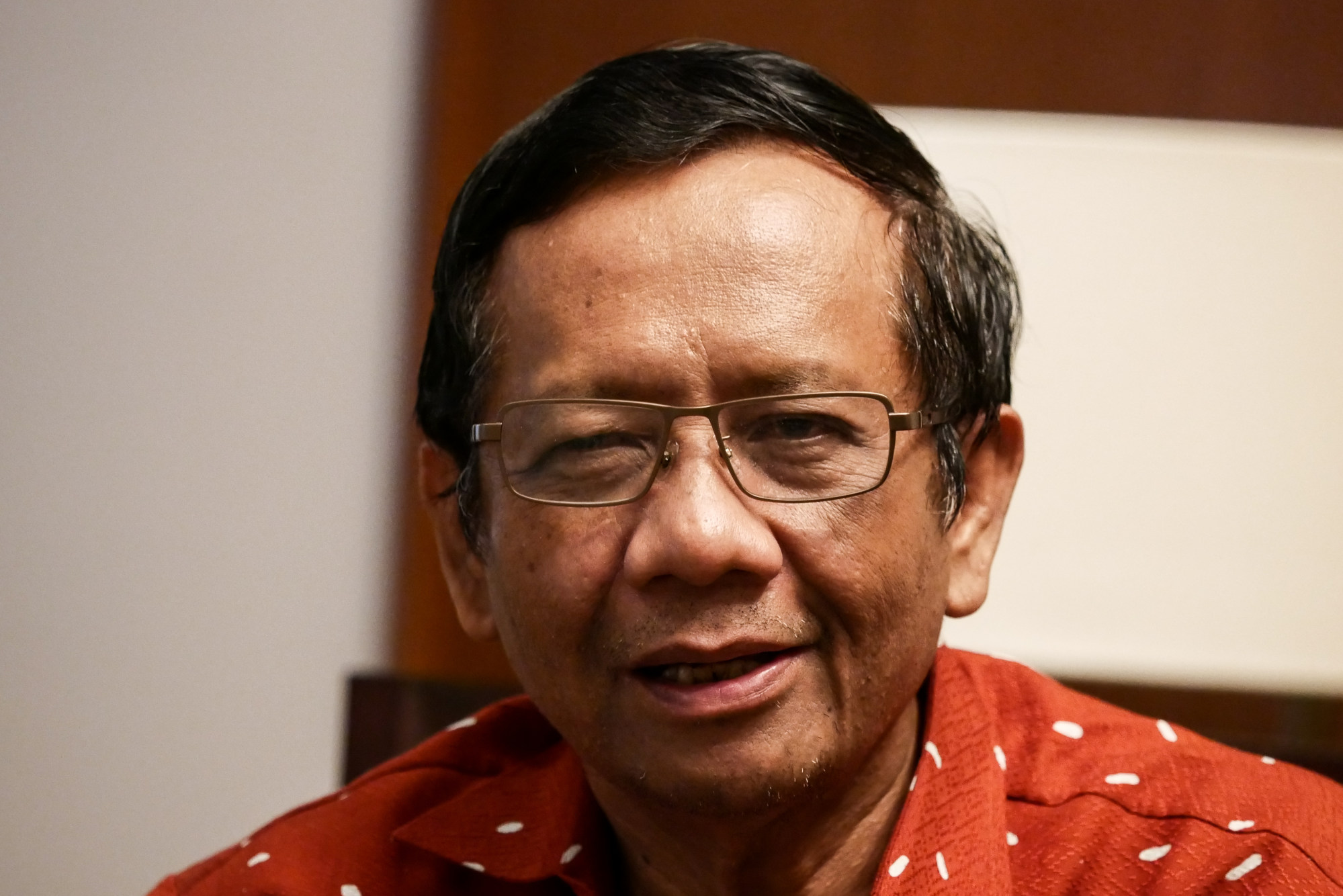

Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs Mahfud MD has floated the idea of outlawing homosexuality by revising the penal code, and tweeted his support for anti-LGBT legislation as part of an online discussion in response to the scandal.

“Back in 2017, the government had already sought to add anti-homosexuality clauses to the penal code but civil society groups protested against it,” he told reporters in Bali on May 18.

He said that in the draft bill, gay sex and public expressions of homosexuality would be outlawed. He went on to suggest that the government and parliament should just pass the bill, regardless of opposition from civil society, adding that dissenters could always file for a judicial review with the Constitutional Court.

Revisions to the Indonesian penal code, inherited from the Dutch who colonised the archipelago for a period of about 350 years, are currently ongoing in parliament. Deputy Speaker of the House of Representatives, Sufmi Dasco Ahmad, said he expected the process to be finalised this year.

LGBT history

Amsterdam-based Indonesian historian Joss Wibisono said he found it ironic that gay Indonesians like Ragil had to leave the country to be able to express their sexuality freely. In the colonial era, the Netherlands East Indies – as Indonesia was then known as – had been a safe haven for European LGBT people.

“Unlike British colonies, which had anti-sodomy laws, the Indies was quite liberal in this sense,” he said. “Bohemian enclaves, notably in Bali, soon sprung up, populated by Europeans and Westerners who were misfits in their own societies, including gay people.”

Notable LGBT figures of the day included Walter Spies, the German primitivist painter who moved to Java in 1923, and later to Ubud, Bali, in 1927, as well as Canadian-born musicologist and composer Colin McPhee.

But in 1938 the colonial authorities, under Governor General Alidius Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer, launched a crackdown on gay men. Between December 1938 and May 1939, around 225 men were arrested across the Indies, and charged with having conducted same-sex sexual relations with persons under the age of 21, which was against the law.

In today’s age of identity politics, the LGBT community remains as vulnerable as it was then, said Dede Oetomo, a veteran gay activist and founder of Indonesia’s oldest LGBT advocacy group, GAYa NUSANTARA.

“We have seen public figures use public sentiments against LGBT people to seek rapport with the more conservative constituents,” he said.

Bisexual Superman comic ruffles feathers in Muslim-majority Indonesia

Dede said if the Indonesian government proceeded with its plan to penalise homosexuality, it would be an unprecedented move in the wrong direction.

Meanwhile, as an openly gay man living in Jakarta, Pahlevi hoped that Indonesia’s leaders could see that the country had other priorities than persecuting its LGBT citizens.

“Why not tackle areas where the real crises lie, such as rampant corruption and the environment instead?”