Indonesian historian Onghokham’s ‘fearless’ life as gay Chinese man, Java expert celebrated in biography

- The book delves into Onghokham’s struggle to come to terms with his sexuality, his advocacy of Chinese assimilation in Indonesia, and his love for Javanese culture

- After he had a stroke in 2001, Onghokham tasked his close friend and academic David Reeve to work on the biography and share the truth of his colourful life, warts and all

When a prominent Indonesian personality authorises someone to write their biography, the final product almost inevitably takes the form of a hagiography.

The Javanese, Indonesia’s largest ethnic group, have a saying: “Mikul dhuwur, mendhem jero”. It translates to, “when you lift, lift high, but when you bury something, dig deep”. This axiom urges people to highlight good deeds, while simultaneously playing down any flaws that society frowns upon.

But for the late Ong Hok Ham – better known as Onghokham, one of Indonesia’s most celebrated social historians and a known expert on the Javanese – the truth was always a greater objective than any social taboo.

Indonesian-Chinese author Marga T on childhood trauma: ‘it gave me cancer’

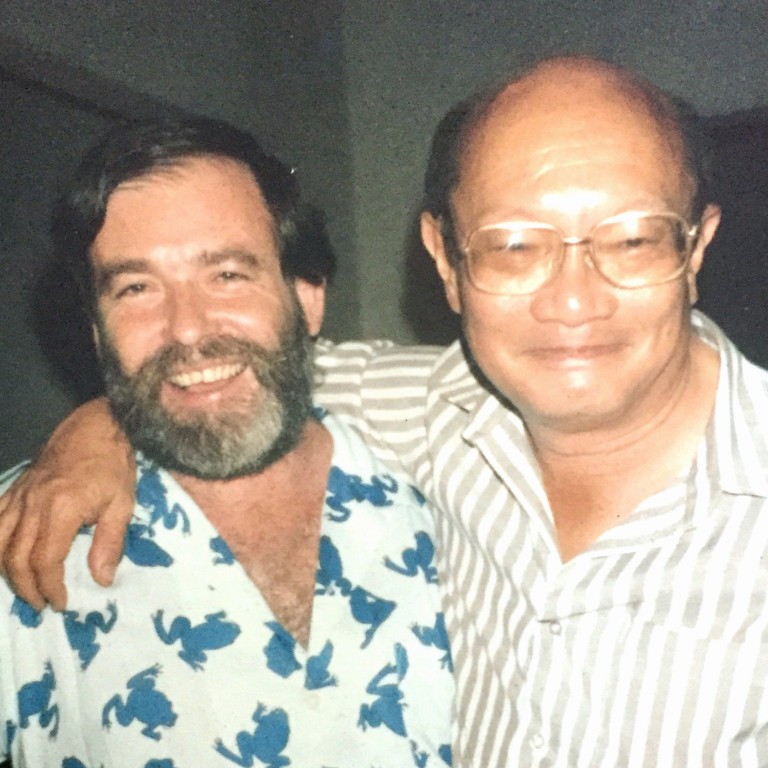

After he suffered a major stroke in 2001 at the age of 68, Ong permitted his friend David Reeve, an Australian academic, to start writing his biography.

“I first met Ong in 1984 at the University of Indonesia, and a close friendship developed over time,” Reeve recalled. “Both Ong and I often said at the time that one day, I should write his biography.”

Reeve said Ong had charged him to “tell everything about his life”, leaving nothing out, including Ong’s sexuality, which had remained a secret from the public.

In the biography, Reeve shares intimate details of Ong’s life as a gay man, his struggle to come to terms with his sexuality and the partners he had over the years.

To support Reeve’s effort, Ong gathered his family members and asked them to offer the Australian their full cooperation, even adding: “I want the family to tell David everything bad about me!”

Assimilation advocacy

Born into a wealthy Chinese-Peranakan family in 1933 Surabaya, Ong was a living witness to modern Indonesian history: from the last nine years of Dutch rule ending in 1941, followed by the Japanese occupation in 1942, the declaration of independence in 1945, the subsequent independence war, the rule of presidents Sukarno and Suharto, as well as the birth of Reformasi, the movement to dethrone Suharto.

His family was related to three distinguished Chinese-Peranakan families in East Java – all Dutch-educated and occupying prominent social positions in the Netherlands East Indies, as Indonesia was then known as then. Notably, from his mother’s side, Ong was descended from the 19th-century sugar magnate Han Hoo Tong of Pasuruan.

A colonial-era law is why Chinese-Indonesians can’t own land in Yogyakarta

In spite of Ong’s privileged upbringing, he was a precocious child and was cognisant of the tensions and racial divide between the ethnic Chinese population to which he belonged, and the indigenous Javanese.

Later, as a young intellectual in newly independent Indonesia, Ong advocated for the complete assimilation of Indonesian-Chinese into Indonesian society, as opposed to their integration with Chinese attributes intact.

According to Reeve, Ong was impressed to witness how well ethnic Chinese in Thailand and the Philippines had assimilated, during his visits to both countries in 1957, when he was research assistant to Cornell University scholar G. William “Bill” Skinner.

When he later came across a group of well-assimilated Chinese in the town of Sumenep, Madura, in East Java province, he became convinced that total assimilation was possible for Indonesian-Chinese.

Around that time, the Chinese community in Indonesia was divided between assimilation – which was pushed by the government – and integration. President Suharto subsequently enforced assimilation by banning expressions of Chinese culture, including the use of Chinese surnames. After his presidency ended in 1998, some Indonesian-Chinese started to reconnect with their roots, making integration a more preferred option.

The Sumenep Chinese, Ong wrote, “look Madurese and are treated as Madurese. I saw with my own eyes almost 100 per cent assimilation into Indonesian society”.

‘Change was needed’: Indonesian-Chinese revive original surnames

But Charles Coppel, an Australian historian specialising in the study of Indonesian-Chinese, pointed out that Ong’s views on assimilation would change over the course of his life.

“He moved away from being something of an activist for assimilation,” said Coppel, who had first met Ong in Jakarta in the 1960s.

“By contrast, others like Junus Jahja (Lauw Chuan Tho) intensified their assimilation activism,” he said, adding that Ong was too intellectually curious to be stuck in a static position.

Love for Java

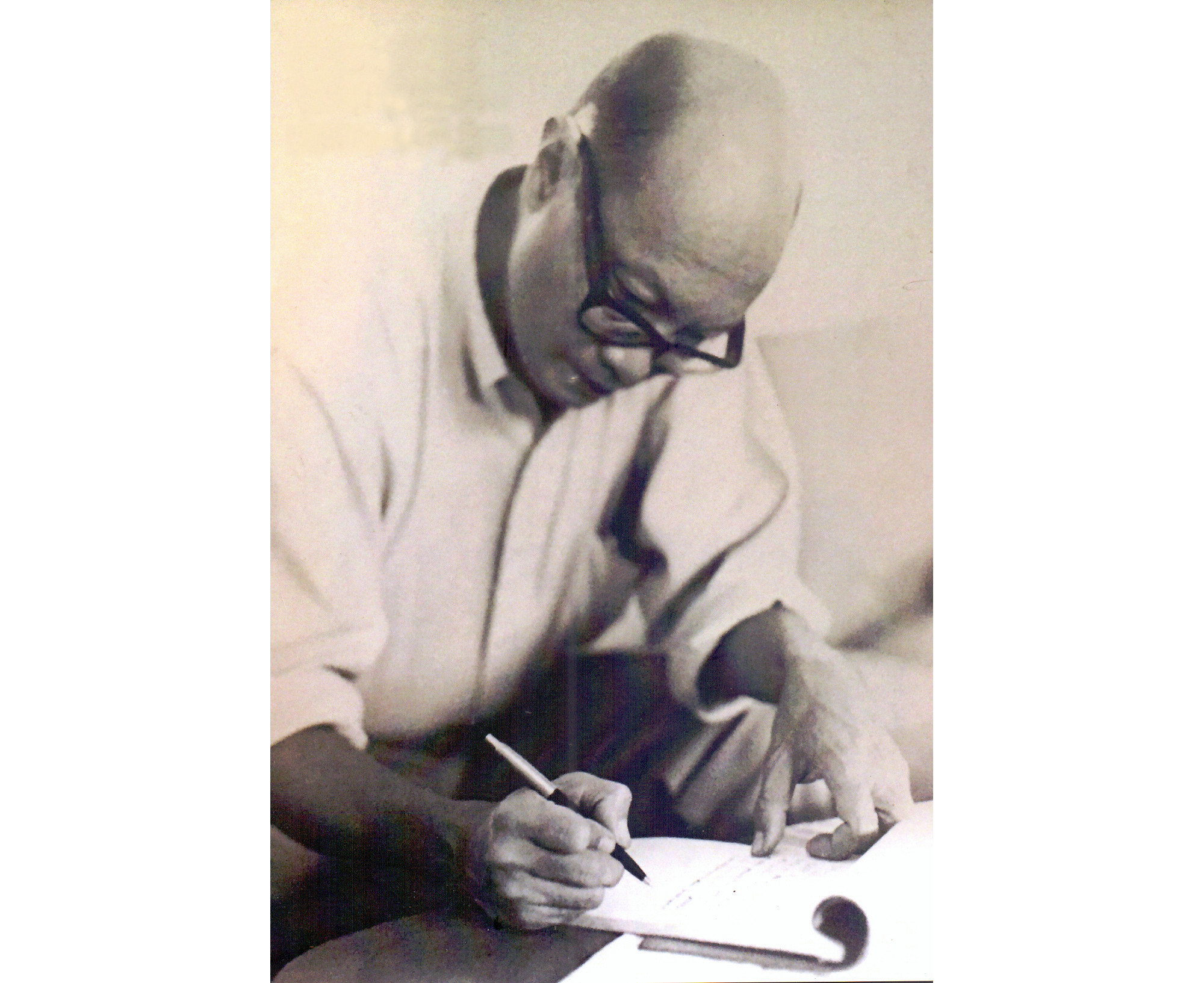

Javanese culture became one of Ong’s enduring loves. He duly became an expert on the history and traditions of Java.

His 1975 Yale University dissertation, “The Residency of Madiun: Priyayi and Peasant in the Nineteenth Century”, along with his book, The Thugs, the Curtain Thief and the Sugar Lord (Power, Politics and Culture in Colonial Java), are now classic works in their genre.

Through the late 1950s and early 1960s, Ong became an unofficial correspondent for various foreign researchers of Indonesian studies by keeping them updated on developments in the country as the government became anti-Western and turned off access to most scholars in the last years of Sukarno’s rule.

He socialised with people from the press corps, partied and had dinners with celebrities, diplomats and politicians alike. That was his data-gathering

Despite Ong’s research accomplishments and his long-lasting friendships with some of the most renowned scholars of Indonesian studies, he was ambivalent about making his mark in academia.

“Ong was an intellectual who didn’t care too much about climbing up the academic ladder,” said Aboeprijadi Santoso, former Radio Nederland journalist who knew Ong from his Amsterdam years. He added: “He once told me he might have misplaced his Yale diploma.”

Santoso also said Ong’s method as a historian was unorthodox.

“Instead of burying himself in stacks of notes, he went around visiting traditional markets and talked to the traders there. He socialised with people from the press corps, partied and had dinners with celebrities, diplomats and politicians alike,” he said. “That was his data-gathering.”

Indonesia’s Singkawang is ‘most tolerant’ city in Muslim-majority nation

Coppel said Ong was “one of a kind” and his identity “transcended generalisations about the Indonesian-Chinese”.

Heather Sutherland, one of Ong’s close confidantes – and through whom he developed a friendship with British actress Miriam Margolyes, the actor who played Professor Sprout in the Harry Potter movies – warned against using labels for Ong, especially his being Chinese “to downgrade his sense of belonging”.

“But anyone who knew Ong and was familiar with his work, could never utterly doubt that he was the product of his homeland … These multiple facets of his ‘Indonesian-ness’ strengthened his ability to be both inside and outside – a sometimes uncomfortable position that nonetheless can be very useful to the professional observer,” Sutherland once wrote of Ong.

Chinese-Indonesians in the Netherlands feel the pull of home

Reeve is also in no doubt about Ong’s inherent love for Indonesia.

“He chose Indonesia three times: first in 1952, when at the age of 19 he decided to become an enthusiastic citizen of the new republic. Second, in 1975, when he chose to return to Indonesia from study in America, and finally in his final illness, he chose to leave behind a research foundation devoted to Indonesian history.”

But this never stopped Ong from criticising Indonesia when he felt criticism was due. He particularly had harsh words for the post-independence intellectual climate in his homeland, which he characterised as self-absorbed and insular.

“We, as a nation, are extremely obsessed with ourselves … we believe what is different is never as good or beautiful as what is Indonesian. This is excessive narcissism,” Ong wrote.

Will a video about ‘being gay in Indonesia’ lead to an anti-LGBT law?

Away from his intellectual pursuits, Ong was a social butterfly, presiding over his famed fun court by throwing extravagant parties at his home in Jakarta.

“Ong was an unapologetic hedonist,” Indonesian feminist and author Julia Suryakusuma said. “His parties were legendary and everyone coveted an invitation to his house. He was also an accomplished cook and would serve unusual gourmet fares for his guests.”

Ong’s search for his Indonesian identity as someone from a triple minority background – Chinese, non-Muslim and gay – ran parallel to his own journey coming to terms with his sexual identity.

Just as he lived his life fearlessly, he will live on in Reeves’ biography, where his strengths, complexities, excesses and flaws as a human being are shared with the world, warts and all.

The new biography of Onghokham, To Remain Myself, by David Reeve, is due to come out in July in Asia and Australia.