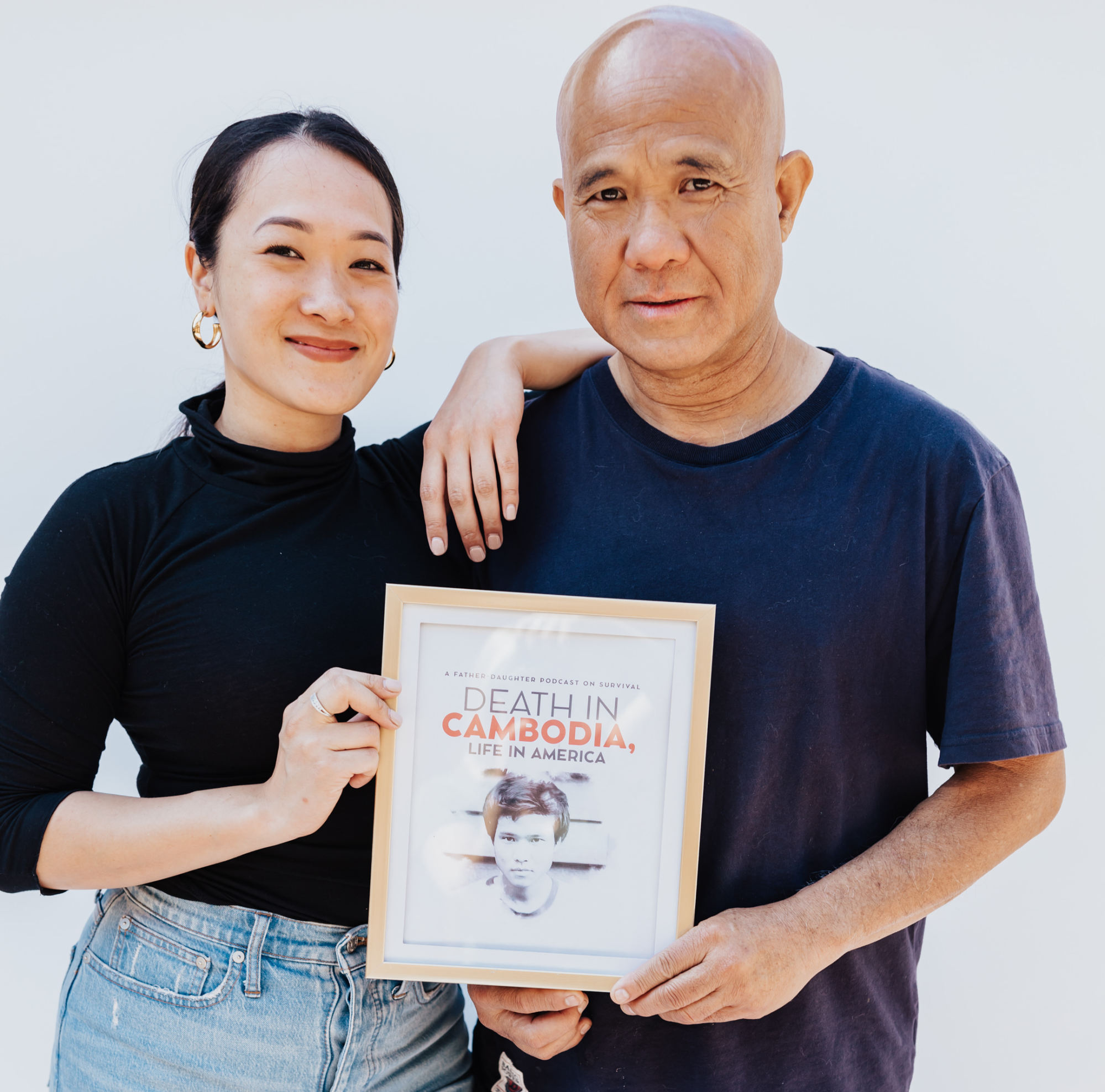

Khmer Rouge survivor in the US opens up on escaping genocide in father-daughter podcast

- A California-based businessman who grew up in Cambodia during Pol Pot’s regime is sharing his story in podcast helmed by his daughter

- Dorothy Chow, who produced and marketed the two-season podcast, hopes their story will strengthen ties between refugee parents and their children

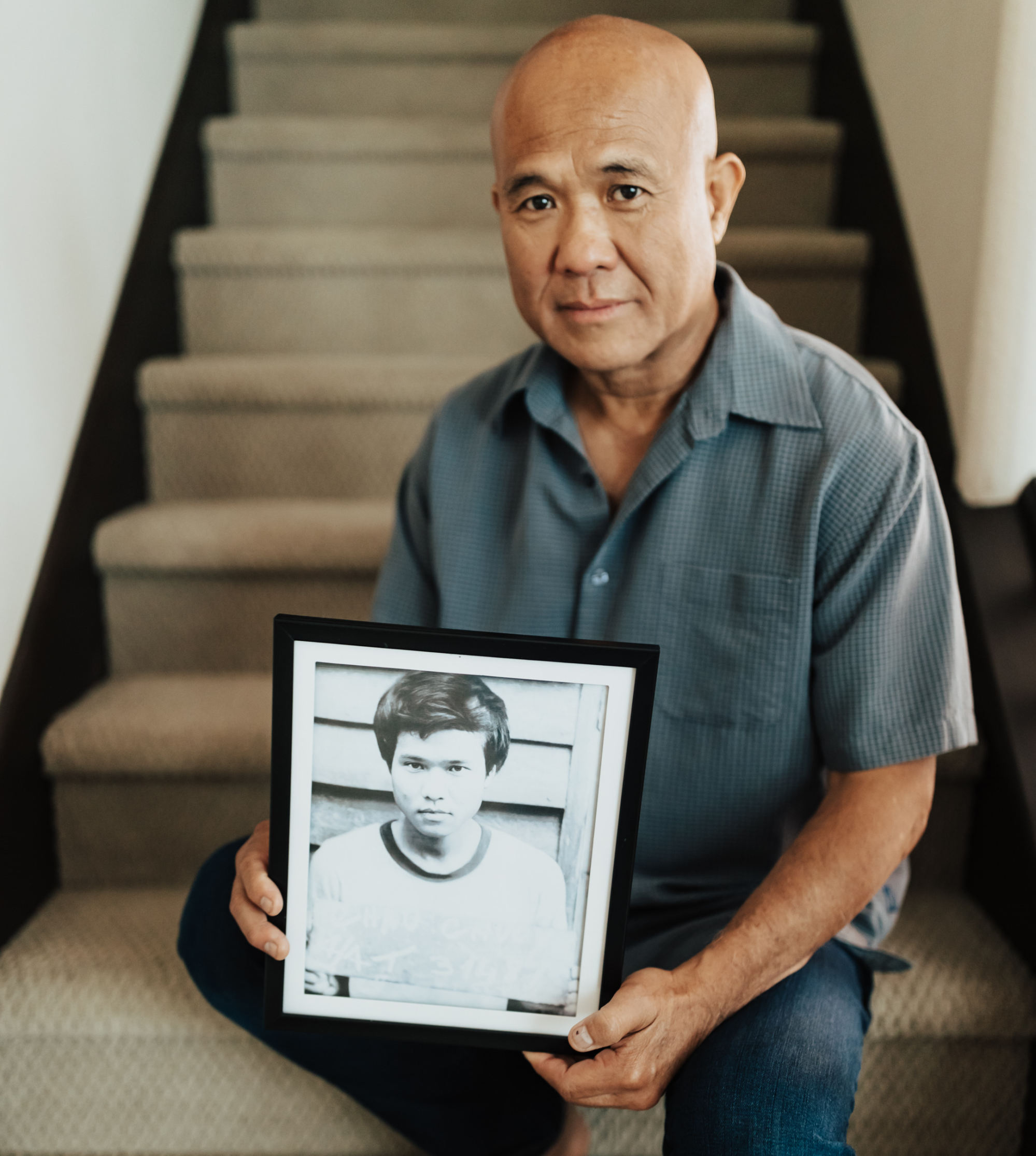

Robert managed to escape and started a new life at 16 in America, where he established a doughnut empire with some 60 outlets and now owns multiple businesses in the baked goods industry.

He buried himself in work, never allowing himself to revisit past trauma. “I had spoken to all my kids briefly here and there at family dinners, but I never allowed myself to get that deep,” he said.

“Sometimes you just stop yourself before it gets too painful.”

But Dorothy felt compelled to help Robert finally tell his story and in turn, understand the experiences that shaped her father.

After a false start with an autobiographer, they turned to podcasting.

“After surviving genocide, starvation, near-death, torture, you can never look at the world the same,” Robert said. “You feel you’re given a second chance at life because you weren’t supposed to live.

“You could have easily died like everyone else and now that you are living, you appreciate the very small things. I have become a very successful businessman and have made a decent life for myself – but if you took it all away tomorrow, I would be ok.”

Starting the healing process

Having his daughter take the lead in telling his story also allowed him to be vulnerable in a safe space, and sharing his story helped Robert begin to heal from his past.

“Every time I had nightmares, it was always about that period in my life; either I was about to die or was being chased. I never dreamed about my good life in America,” he said.

“But after sharing my story on the podcast, I feel a weight lifted. I feel healed.”

They risked their lives saving family photos from Khmer Rouge

Father and daughter have also enjoyed a stronger relationship from working on the podcast, as Dorothy developed a better understanding of her dad after learning about the trauma he lived through.

“I’m not proud of it, but I had lots of resentment towards my father growing up,” she said. “He was a strong, hard, scary figure in our family who never showed emotion or ever cried in front of us.”

She has developed a new sense of empathy and compassion for him and other survivors of the Khmer Rouge.

“After starting the podcast and learning about the horrors of his past, I realised he was ‘hard’ and ‘strong’ not because he had to be, but because he didn’t know anything else,” she said. “He put financial success first because he knew what starvation felt like.”

It wasn’t until this podcast (and therapy) that I learned intergenerational trauma from the Khmer Rouge is a very innately ‘Cambodian experience’

Dorothy has reflected on her childhood with these new lenses, and understood that her parents tried their best with the hand they had been dealt. It also changed her relationship with her identity and ethnicity. Before the podcast, she tried to hide her Cambodian background and told people she was Chinese.

“My parents weren’t very proud of the country of Cambodia due to genocide that happened to them in their youth,” said Dorothy, whose family is Chinese-Cambodian.

“It wasn’t until this podcast (and therapy) that I learned intergenerational trauma from the Khmer Rouge is a very innately ‘Cambodian experience’.”

Dorothy oversaw production and marketing of the podcast and plans to turn her father’s story into a film.

‘Overwhelming’ support globally

Support for the Death in Cambodia, Life in America podcast has been “overwhelming”, with listeners contacting Dorothy, saying that they have been inspired to ask their parents and grandparents about what they went through

The strong reception encouraged Robert to speak out more. “Every time my daughter tells me that people are supporting us, and thanking us for sharing my story, I feel safe and it makes me want to share more,” he said.

“Representation and validity of pain matters,” Dorothy said. “I wasn’t only giving a voice to my father’s story, I was giving a voice to every single Khmer Rouge refugee out there – both living and gone. And that is powerful.”

Dorothy also hopes to build bridges between American children and refugee parents, by helping children understand and accept the trauma their parents underwent.

“It makes me so happy that I am able to teach the next generation something about life. Life is so precious,” Robert said. “As long as you are still breathing, never give up. Chase your dreams. Keep going. Do not waste it.”

*The difference in the spelling of their surnames is due to an error made on Dorothy’s birth certificate