Death penalty easing a step towards ‘new Malaysia’ but worry over free pass for criminals remains

- Malaysia’s move has raised hopes other Southeast Asian countries can follow suit

- Reform reflects changing attitudes in Malaysia since 2010, with advocates saying good government reflects a duty to protect and improve lives rather than punish

Rizalni Mohamad, 46, missed his mother’s death – and has been unable to see his ailing father – while waiting out 17 long years on death row in Malaysia’s Perlis prison over a conviction for trafficking cannabis.

“Everyone inside the prison was very happy,” said his sister Hayati Mohamad, 42, after breaking the news to Rizalni.

Judges can still order the death penalty but the revision culls the “mandatory” death clause from sentencing rules, meaning more than 1,300 people in jail can ask for judicial review of their cases, or have hope of a commutation of sentences to 30-40 years’ imprisonment instead.

Until the move, Malaysia, alongside neighbouring Singapore, had some of the world’s harshest penalties for drug trafficking.

Amnesty International, which closely monitored the death penalty in Malaysia, reported that more than 120 prisoners were hanged for drug offences from 1983 to 1992, with an average of 15 to 16 executions per year between 1980 and 1996. A moratorium on executions has been in place since 2018.

Just last year, the city state executed two Malaysian drug mules despite strong international objections, including one that came from billionaire Richard Branson of Virgin Group.

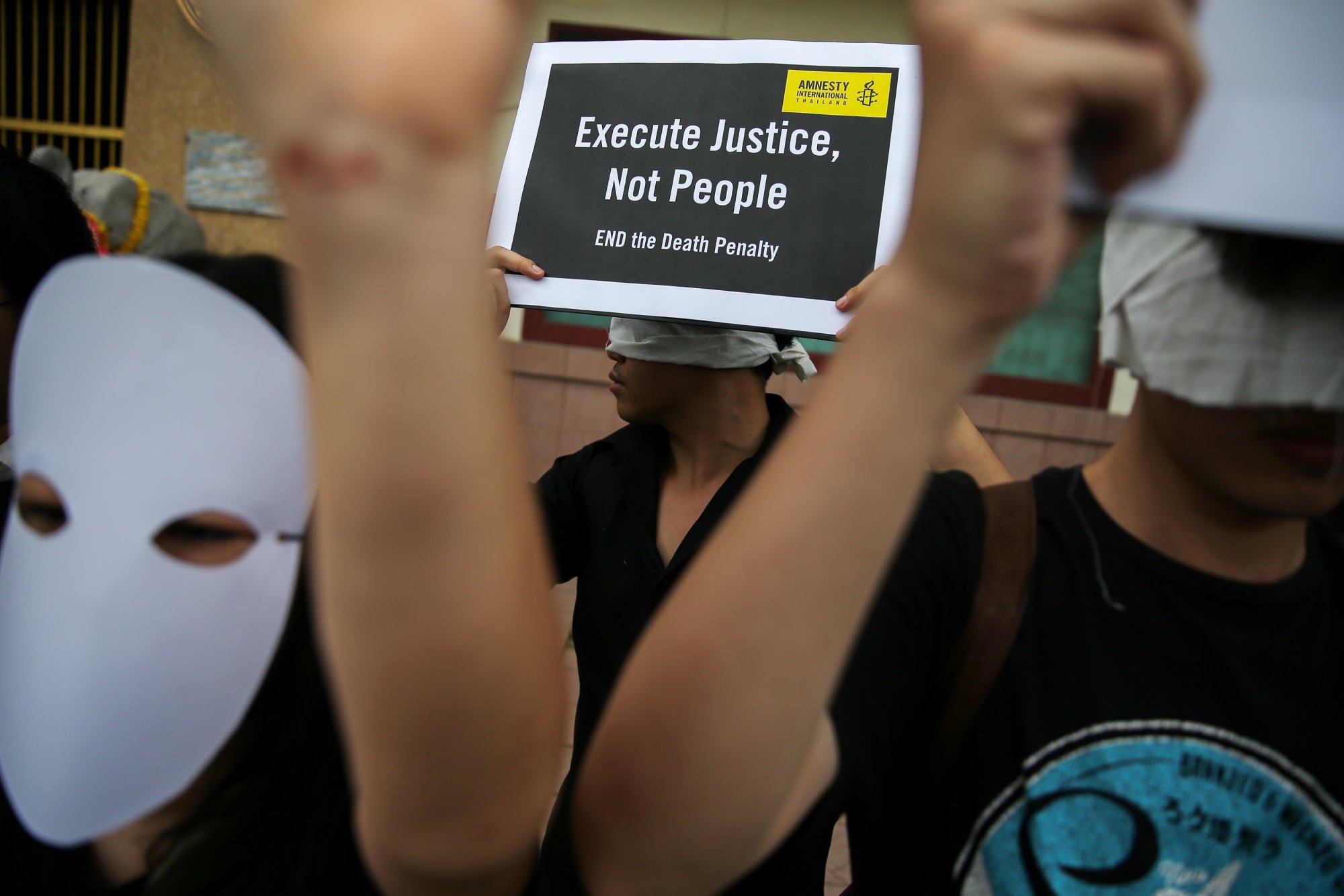

But Malaysia’s softening of its stance has raised hopes that other Southeast Asian countries that still have death on their statutes – including Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam – could follow suit, although Myanmar’s junta has reversed course by executing four people last year accused of violence after the military’s takeover.

Rizalni’s mistake, his sister says, was to hitch a ride in a friend’s car in Kulim, near Penang, back in 2006, which was stopped by police at a petrol station where they found 4kg of marijuana in the car.

Hayati said she herself looked at the death penalty differently once it was meted out to her family member. “When it happens to one of your own, and you know the facts of the case, you understand that the punishment is inappropriate,” she said.

Hayati now works with Shamala Manickarajah on an advocacy group for the families of the 1,318 people who are on death row.

Shamala’s childhood friend Raja Sanjivi was also hitching a ride with a friend when they were stopped by police, who discovered drugs in the car leading to both of them being charged under the dreaded Section 39B of the Dangerous Drugs Act which condemns people trafficking, offering to traffic, or assist in trafficking with the mandatory death penalty.

“The person who drove the car died recently of diabetes,” she said. “But Raja is still inside.”

Drug offences

A disproportionate number of people are languishing on death row in Malaysia’s jails for drug offences.

According to the Prison Department, 870 inmates or 66 per cent of them are incarcerated under the Dangerous Drugs Act.

A relic of the British colonial era, the act did not carry a death sentence until 1975 when the mandatory rule was introduced.

It was made harsher in the 1980s under former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, who viewed drug crime as one of the country’s most important security concerns and adopted a “no mercy” policy against convicted individuals.

Speaking to This Week in Asia, Shamala also shared the plight of a family whose son was incarcerated under the Firearms Act – which also carries the mandatory death penalty – for discharging a pistol he found on a field, which he thought was a toy gun.

“He has spent 11 years in jail for firing that gun into the air,” Shamala said. “He did not hurt anyone.”

Originally intended to deter people from committing crimes, cases such as these have been used to expunge the mandatory aspect of the death penalty, which stripped leeway from the courts to deliver sentences matching the facts of the crime.

Under the revised law, judges can now instead opt for the lesser sentence of life imprisonment for a term between 30 and 40 years, plus 12 lashes of the cane.

“We cannot arbitrarily ignore the existence of the inherent right to life of every individual,” said Deputy Law Minister Ramkarpal Singh who tabled the amendments in parliament on Monday. “The death penalty has not brought the results it was intended to bring.”

His predecessors at the law ministry made their unease with the death penalty heard as early as 2010 when then Law Minister Nazri Aziz said that “if it is wrong to take someone’s life, then the government should not do it either”.

It however only went mainstream in 2018 after Mahathir’s second stint as a prime minister where his administration issued a moratorium on executions as it reviewed whether to keep or amend the law.

The late VK Liew, who was Mahathir’s law minister, said the move was part of their vision for a “New Malaysia”.

“New outlook, new hope, where everyone has a right to life and in line with international human rights,” said Liew, who died in 2020.

A further change of attitudes emerged in 2022 when then Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin openly discussed the merits of the medicinal use of marijuana, already decriminalised in neighbouring Thailand.

Death penalty still remains

Deputy Minister Singh was at pains to spell out the changes, after many posts emerged panning the government for what they think is abolishing the death penalty altogether.

“The death penalty is not abolished. The death penalty still remains, just not mandatory,” Singh said on Twitter.

Resistance has come from families of victims of those on death row, who made their grievances heard in the corridors of the parliament building while the law was being debated in the chambers.

Among them was Tan Siew Ling, mother of Annie Kok Yin Cheng – who was raped and murdered at the age of 17 in 2009 – who sobbed inconsolably in front of the press’ cameras while holding tight a framed portrait of her daughter.

“This discretionary death penalty policy only protects criminals and not victims [nor] public interests,” said Christina Teng from Protect Malaysia, a coalition of NGOs for victims’ families.

She argued killers would walk free under the new law as judges would decide against handing out death penalties because of not wanting “blood on their hands”.

But advocates of repeal say good government reflects a duty to protect all and improve lives rather than punish.

“The government cannot be the platform to exact revenge, nor should it inflict harm and cause more tragedies,” said Dobbie Chew, of the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network.

For her and others with family members on death row, their next hurdle is at the Federal Court – Malaysia’s highest court – which will hear their application to review their death sentence through a newly opened avenue for a judicial review accorded under the new law.

Hayati hopes the courts will eventually see that her brother has suffered enough and release him soon so he could be with his father, who is paralysed.

“His life has passed its prime,” she said of her brother. “Let him devote the remainder of it to be a good son.”