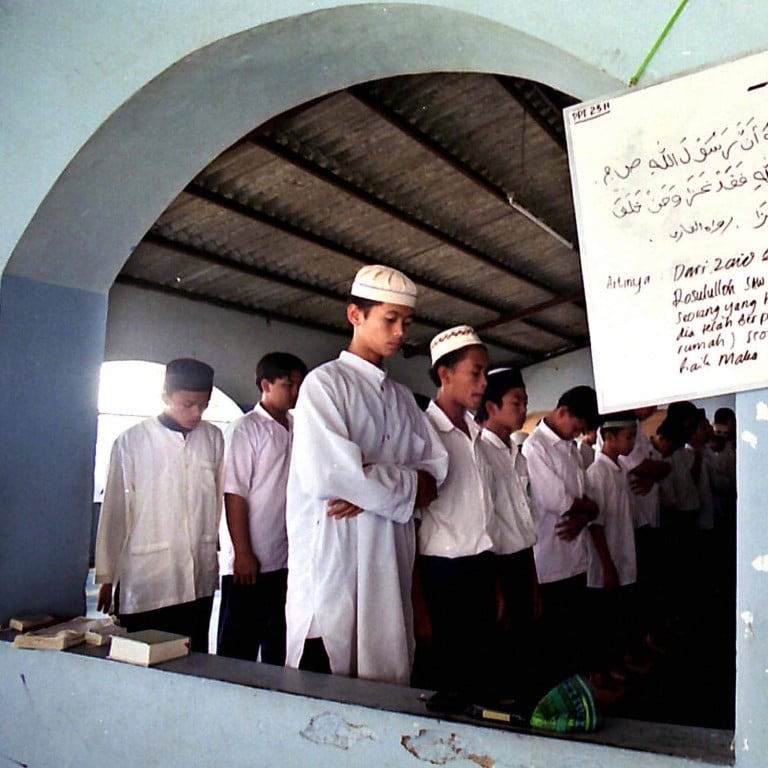

‘Tip of the iceberg’: Indonesian teen’s death spotlights rising bullying trend in religious schools

- Bintang Balqis Maulana, 14, was reportedly beaten by four senior students over three days, in an incident that has sparked outrage across social media

- Activists say authorities appear ‘toothless’ when handling ‘pesantren’ bullying cases, urge government to take concrete steps to end school violence

Bintang Balqis Maulana, a 14-year-old student at the Al Hanifiyah pesantren, in Kediri, East Java, died on February 23, reportedly after being severely beaten. Four senior students aged between 16 and 18 have been taken into custody by the police and subsequently declared suspects in his murder.

“From our reconstruction of the case, we have learned the victim was the recipient of repeated beatings over the course of three days,” Kediri Police Chief Bramastyo Priaji said on February 29.

The death of the teenager from Banyuwangi town has provoked outrage across social media, where Indonesians have been venting their anger, largely towards the four perpetrators but also at the school management.

“So furious the pesantren folk feign innocence in all this! They were at the very least negligent!” wrote Facebook user Renaldi Saputra.

Surabaya resident Lucky Anwari, 35, said he was shocked by a video clip on social media showing the state of Bintang’s body.

“The bruises and injuries were there for all to see, and yet his school initially told his parents he had taken a fall in the bathroom and even asked them not to uncover his shroud before burial.”

Bintang’s death has become emblematic of a culture of violence and bullying in schools that has worsened in recent years. The Indonesian Commission for Child Protection (KPAI) recorded 3,877 complaints from parents whose children had experienced violence or bullying at school last year.

Cleric Aan Anshori, from the progressive Gusdurian Network and spokesman for the Jombang Network of Pesantren Alumni, said the known cases of physical violence at pesantren were just “the tip of the iceberg” because many more were going unreported.

“We suspect there have been more cases where the parents chose not to file police reports,” he said.

Anshori noted that since 2022 there had been 12 recorded cases of extreme violence at various pesantren in East Java alone, six of which proved fatal.

“It’s time for the state, through the Ministry of Religious Affairs, to step in and do something to prevent future tragedies at pesantren,” he said.

Education institutions run by religious organisations in Indonesia fall under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, while their non-religious counterparts operate under the Ministry of Education and Culture.

Indonesia’s Jokowi denies cover-up claims in brewing school blasphemy scandal

“The first thing the ministry must do is to have all boarding schools register themselves. Otherwise, how could they hope to regulate them?” Anshori said, pointing out that Al Hanifiyah, Bintang’s school, was not registered with the ministry.

Anshori claimed that in East Java alone, there were about 1,200 unregistered pesantren. He called on the ministry to register such schools and ensure they apply measures to create an anti-bullying environment.

The ministry should also form a national anti-bullying task force to root out violence at pesantren, he added.

“There’s no time to lose. Pesantren management must necessarily open themselves to reform so that parents who have entrusted their children don’t lose faith in an institution that has educated millions of Indonesians for centuries,” he said.

Waryono Abdul Ghafur, director of Diniyah Education and Pesantren, a subdivision of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, said on Friday his department would look into Bintang’s case and “take appropriate but measured steps” to prevent similar incidents from recurring.

“We are open to suggestions and input from all the concerned parties,” he added.

Nia Perdhani, 40, a mother of two from Pati, Central Java, said she was saddened by Bintang’s death.

“But it doesn’t mean I’ve lost faith in the institution of pesantren,” said Perdhani, whose children attend pesantren.

She urged parents to foster good, honest communication with their children, adding that in most bullying cases at school, “the students didn’t tell their parents they were being harassed until it was too late”.

Perdhani said bullying did not only happen at pesantren.

In another high-profile case, four students at a private upmarket school in Serpong, West Java, were arrested for assaulting a 17-year-old fellow student in early February. One of those arrested is the son of Indonesian actor Vincent Rompies.

Indonesian school shaves hair of 14 girls over teacher’s hijab complaint

Social activist and blogger Rina Tiarawaty said that while student violence was not limited to religious schools in Indonesia, authorities appeared to handle such cases in pesantren differently.

“Our law enforcers appear to be toothless against these religious bodies, always walking on eggshells whenever they deal with pesantren cases,” she observed.

While some of the perpetrators were prosecuted, she said the institutions themselves were never held responsible as the government “[feared] the displeasure of Islamic organisations [these schools] were affiliated with”.

Tiarawaty said the apparent impunity enjoyed by pesantren in the face of criminal cases had to stop if rule of law was to be upheld.

“So far we have seen pesantren behave like a state within a state,” she said.

Data from Indonesia’s Ministry of Education showed in 2023 there were 39,167 registered pesantren across the country with a total number of 4.85 million students. By comparison, there were around 54 million students at public and private schools.

KPAI commissioner Aris Adi Leksono said his agency recommended that the government and schools devote more resources to anti-bullying campaigns and better access to school counselling, as well as the provision of bullying reporting hotlines for students and parents.

“We can no longer tolerate the increasing trend of violence at school as it always leaves lasting psychological trauma on students,” he said, adding in 2023 there were at least 20 bullying-related student deaths.

Irine Gayatri, a public policy researcher at the National Innovation Agency, said the government must take concrete steps to end violence at school.

“The government and law enforcers can’t be seen to be normalising these incidents through inaction. The perpetrators must be brought to justice,” she said.

Schools where student violence occurred must also bear the brunt of responsibility, she added.

“We should stop talking about having smart cities and how bright our future will be … when we as a nation are incapable of protecting our own children at institutions where they are supposed to be educated.”