Advertisement

Why is Australia warning about war with China? A clue: elections loom

- If Australians are hearing ‘beating drums’ of war, as Minister Mike Pezzullo said, is it because the government thinks bringing up China will win voters?

- Rhetoric about war and security, as well as a fear of China, are deep-seated in Australian politics but are based on a misreading of Beijing’s own interests, experts say

Reading Time:7 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

99+

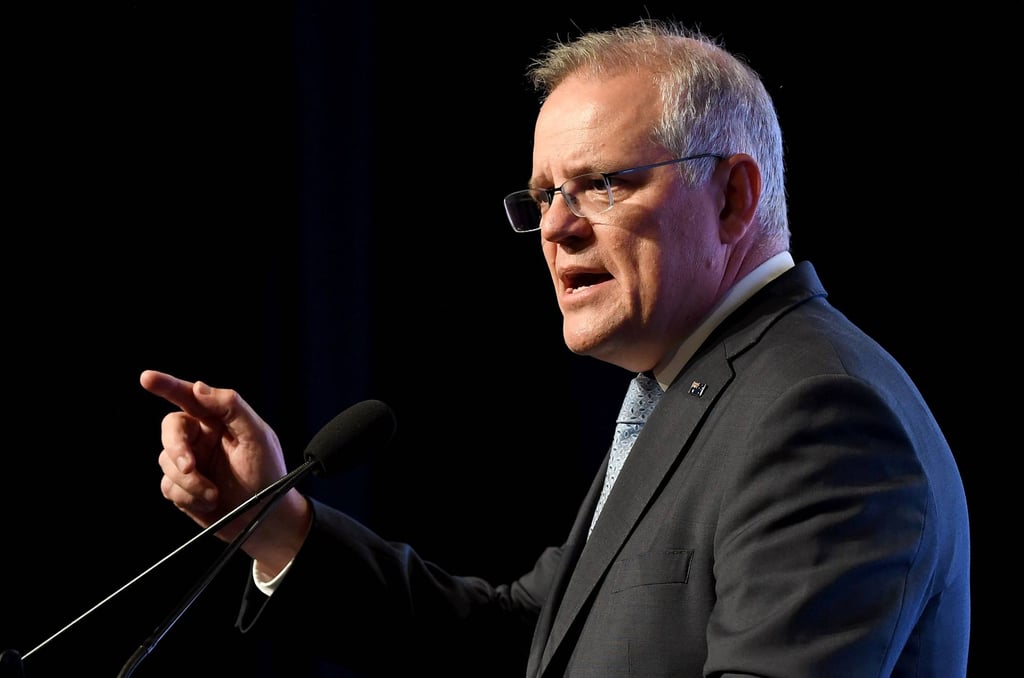

Soon after Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison tweeted that he had spoken to then US president Donald Trump about Covid-19 last April, he called for the World Health Organization to be given the same powers as weapons inspectors when investigating the pandemic in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, where the outbreak was first reported.

Weapons inspectors, usually deployed by the United Nations, are synonymous with war, in particular the United States-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. In the lead-up to the invasion, the US had tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade the UN to authorise the use of force on the grounds that Saddam Hussein had been uncooperative with UN and International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors.

A year after Morrison’s tweet, amid a deepening Australia-China feud over politics and trade, Home Affairs Secretary Mike Pezzullo chose April 25 – also known as Anzac Day, Australia’s day of remembrance for its war dead – to once again hint at war. Free nations, said Pezzullo, could “hear the beating drums” while “bracing, yet again, for the curse of war”.

Advertisement

“By our resolve and our strength, by our preparedness of arms, and by our statecraft, let us get about reducing the likelihood of war – but not at the cost of our precious liberty,” he said.

Defence Minister Peter Dutton also chimed in, saying a conflict between mainland China and Taiwan could not be discounted.

Advertisement

The Morrison government’s talk of war has continued to escalate since the outbreak of the virus last year, to the point that it has eclipsed even the rhetoric emanating from China’s fiercest competitor, the US.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x