The link between Singapore’s Merlion, China’s terracotta warriors and cuddly toys

Familiar cultural images, icons or brands can go a long way towards calming nerves for travellers when on stressful, unfamiliar ground, researchers find

The next time a fellow traveller plonks his bottle of Kowloon Soy Sauce, or the Yu Kee Oyster Sauce on the table as you start dinner in some exotic destination, don’t laugh. These items are as powerful – even for an adult – as that tattered toy bunny you took to bed when you were a baby.

Research shows that adults develop a sense of attachment to icons, probably in the same way as children develop attachments to maternal figures. This phenomenon is built on a human need for bonding. As we grow older, it is no longer our caregiver or our cuddly tody; we direct our attachment to a familiar culture in a process called “cultural attachment”. This can be via affiliation with a social group, allegiance to a set of social values or a nod to familiar cultural symbols. Cultural attachment is important because it affects our reactions to threats.

Researchers, including Professor Ying-yi Hong of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, studied a group of students in a clinical setting. The subjects, who were Singaporeans, had not spent a significant amount of time overseas except for some short-term travel and brief exchange programmes. Importantly, the main cultural attachment of these subjects was undeniably Singaporean.

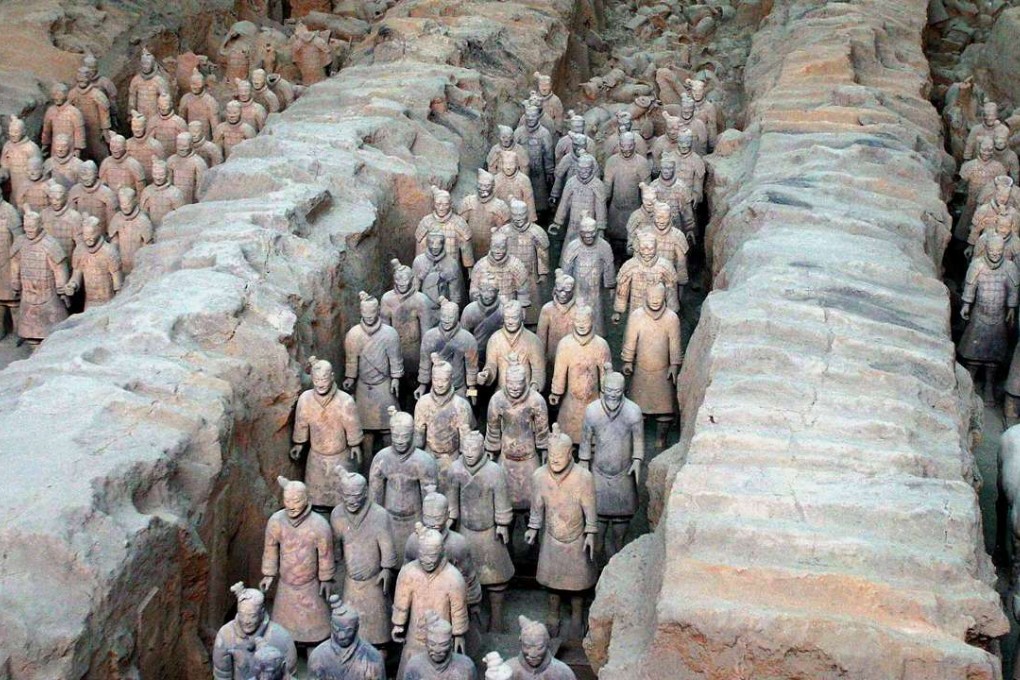

One of the national symbols Singaporeans most identified with was the Merlion – a mythical creature with a lion’s head and the body of a fish that is an icon of the city state. The image was found to evoke similar emotions that participants from the United States had for the Statue of Liberty and Chinese students had for the terracotta warriors of Xian.