Raped by her father as a child, now she helps other incest victims speak up

- Karina Calver was five when her father first raped her, with the abuse continuing until her early twenties

- After breaking her silence, she embarked on a journey of self-healing and is now vocal on the issue of incest rape – especially in the Indian community

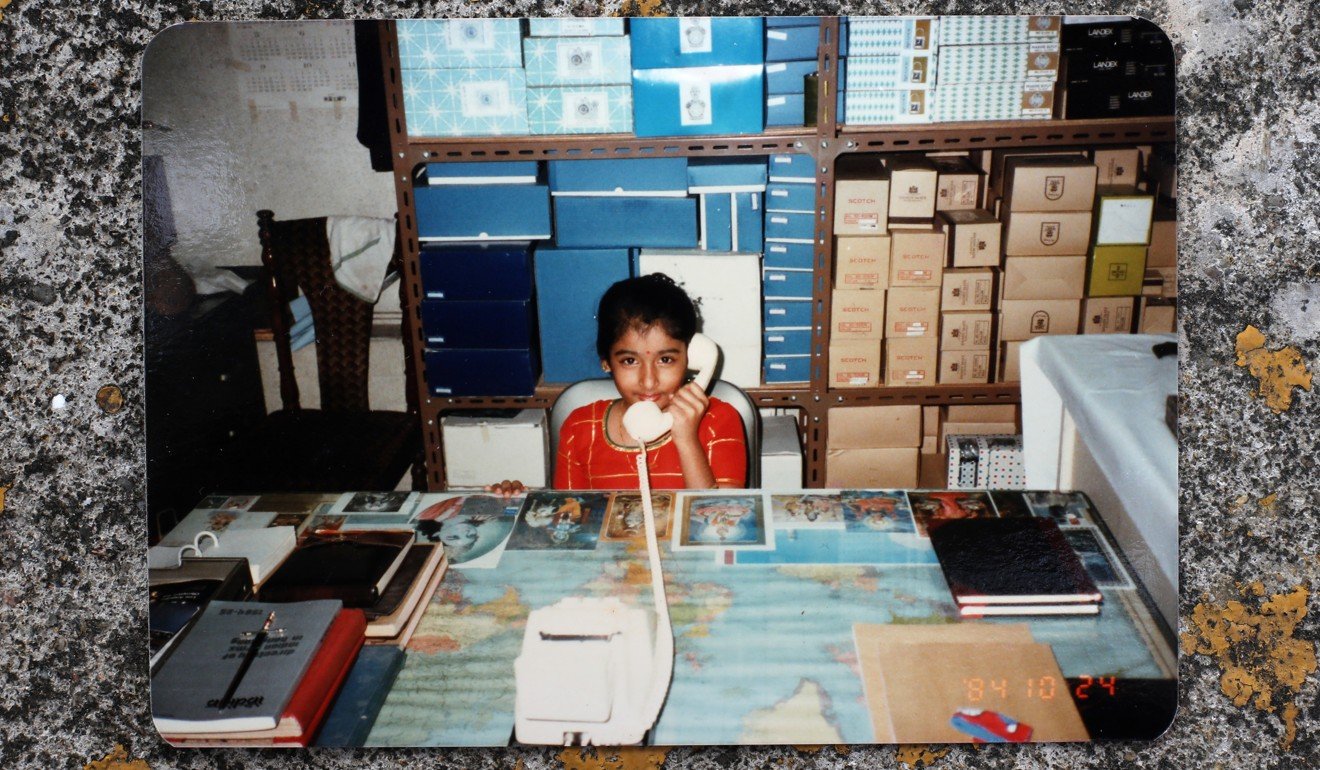

Karina Calver was five years old when her father raped her for the first time at their family home in Hong Kong’s Tsim Sha Tsui neighbourhood. Brainwashed by his narrative that this was an education, she suffered the harrowing ordeal multiple times until her early twenties.

At the age of 17, a conversation with a concerned high school teacher confirmed Calver’s suspicion that she was a victim of child sexual abuse.

“I still didn’t understand the extent of the abuse. I didn’t understand that this was rape, because rape would mean I wasn’t a virgin. He was always telling me that good Indian girls remain virgins till they marry – so I was certain and proud that I was one. I couldn’t connect the dots,” says Calver, now 43.

“At the time, the mind freezes to comprehend what’s going on. We allow ourselves to just live through it in order to survive. Also, I was scared that if I turned him away I’d be forced to leave home and I’d have nowhere to go. I didn’t have the necessary support in place to speak up.”

Calver’s sentiments are echoed by thousands of female rape survivors.

In a 2016 review by the University of Mary Washington in Virginia, which looked at 28 studies of 5,917 female rape survivors aged 14 and older, more than 60 per cent of victims did not label their experience as rape. A recurring theme ran through their stories: they needed time to acknowledge what had happened to them.

When the perpetrator is a parent, it becomes even more challenging for children to identify what is happening to them, experts say. When they do, misinterpretation, shame, family loyalty, fear of retribution and abandonment can deter a child from speaking up.

Four years ago, when Calver turned to a counsellor about seemingly unrelated issues, the full and ugly truth hit home: she was a survivor of incest rape. Shocked and enraged, Calver, then 39, lifted the veil of silence.

“For years, I had battled with low self-esteem and poor confidence. I had struggled in relationships. I’d had therapy on and off for years and I didn’t know myself. But when I confronted my dad, his excuses pained me. I understood then that I needed to move on,” she recalls.

With the unwavering support of her fiancé (now her husband), Calver embarked on a private journey of self-discovery and healing. Armed with faith and resilience – lessons learned from her stoic grandmother – she was determined not to be defined by her traumatic ordeal.

“The shock took multiple counselling sessions to overcome. At first, I rejected my femininity. The way I saw it at the time – being a girl, being feminine – is what got me raped. My husband gave me wings to fly. When I discovered who I am as a woman, I wanted to embrace every part of my physical body. I started working out, shopping online, wearing heels. Being proud of me. And being proud of being a woman,” Calver says.

Guided by the teachings of a Buddhist monk, Calver realised she did not need clothes to validate her femininity. Meditation helped to channel her calmness, she says. Embarking on a degree in counselling helped, too.

“This whole process was necessary for me to know within myself that I am enough. To love me for me and to love life because I won’t let the past hold me back. To forgive from a distance while maintaining boundaries, so I don’t bring toxicity into my life. To be the best version of myself – constantly working with my mind to show compassion, to embrace suffering, to see the lessons behind a traumatic experience. To say I am stronger for this, and for that I am grateful,” Calver says.

A content wife, high-school teacher and part-time counsellor, Calver embraced a simple and mindful life. But again, she felt an overwhelming need to speak up. This time, it was to deliver a powerful message: I will not be silenced.

In 2017, going against cultural norms and her private disposition, Calver courageously spoke out for the first time about her experiences as a survivor of paternal incest.

“Speaking out on the Hong Kong Confidential podcast was the first time I truly owned my story. At first, I felt embarrassed. But it liberated me. I felt limitless. Some people assume survivors speak out for sympathy or because we’re stuck. But that’s not the case. I speak from a place of peace, not anger. Speaking out is a way to help others. To support each other through our stories. To encourage others to own their stories, seeing that we have spoken, we have healed, and that there is life beyond this.”

Feeling safe to speak out is essential for a victim of sexual violation. Rape, sexual abuse and harassment happen everywhere. Why is this not your problem, but mine?

In a timely coincidence, sexual assault allegations against film mogul Harvey Weinstein the same month prompted more than 12 million people around the world to share their experiences of sexual abuse and harassment on social media. When Calver discovered a #MeTooNowWhat? event was in the making in Hong Kong, she did not want to just attend – she wanted to be a part of it.

Working alongside three more ambassadors for sexual safety, she says the event proved a huge success. She decided to lead a similar event for the Indian community. Her intention was to shatter both the delusion that sexual abuse does not affect Indian families and the code of silence around the problem.

The turnout was smaller than she had hoped for. She attributes this to the cultural inhibition against talking about sex and sexuality and the myths and misconceptions around incest.

“I want people to understand the need to talk about sex and relationships. Sons and daughters need to be educated. We need to build an open and free relationship with children, so that they discuss everything from their urges to uncomfortable experiences.”

Gender equality must also be addressed, she says. “The entrenched patriarchy in society makes women vulnerable. Girls and boys are still receiving messages that sex is a man’s role and that they own that part of ‘us’. If a guy sleeps around, it is accepted, but if a girl does, she’s a slut. Telling a girl that she’s a girl isn’t reason enough for her to follow a certain way of behaving. We need to work through such twisted values related to gender.”

Concerned for the safety of every child of every ethnicity, she ponders: “If your child does not feel that he or she can talk to you about sex, how can they tell you if they’ve been harassed or abused? How many of them will be made to feel ashamed or told the family will deal with it privately for fear of tarnishing reputations? Feeling safe to speak out is essential for a victim of sexual violation. Rape, sexual abuse and harassment happen everywhere. Why is this not your problem, but mine?”

Child sex abuse affects children across ethnic, socioeconomic, educational, religious and regional lines. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), one in five women and one in 13 men reported having been sexually abused as a child. From January to September 2018, Hong Kong’s Social Welfare Department reported 209 cases of child sex abuse. But these figures are the tip of the iceberg.

RainLily, a rape crisis centre for female victims of sexual violence in Hong Kong, handled 777 cases of child sex abuse from 2000 to 2018. In 342 (44 per cent) of those cases, the perpetrator was a family member. The average delay in reporting to RainLily was almost 20 years; the longest delay was around 58 years. Only 53 of the 342 cases were reported to the police.

Shrouded in secrecy, stigma and shame, rape and incest are notoriously under-reported crimes. In fact, the WHO categorises incest as a silent health emergency.

Once again, Calver is ready to speak out: this time in her memoir, A Girl’s Faith, available on Amazon and in major bookstores across Hong Kong from February 22. Dedicated to her grandmother “who always spoke her truth”, Calver’s book brings to light many of the messages that can silence a girl. This is more than a story about rape, she says.

“It’s about the child that I was. The colour of my skin and how I was made to feel inferior because I’m ‘dark’. Being bullied at school. Dating and my lack of confidence. Me not knowing me to me knowing me. It’s about the woman I’ve become. Loving myself. A vegan. A minimalist. A Buddhist. And so much more. Readers can take what they need from the book. I want to empower others to own their story, so they can feel liberated and limitless, too.”