How colour-blind people see the world – as if through an Instagram filter – what causes colour blindness, and how an artist uses his to great effect

- Red-green colour blindness – the most common form – affects one in 12 men and one in 200 women

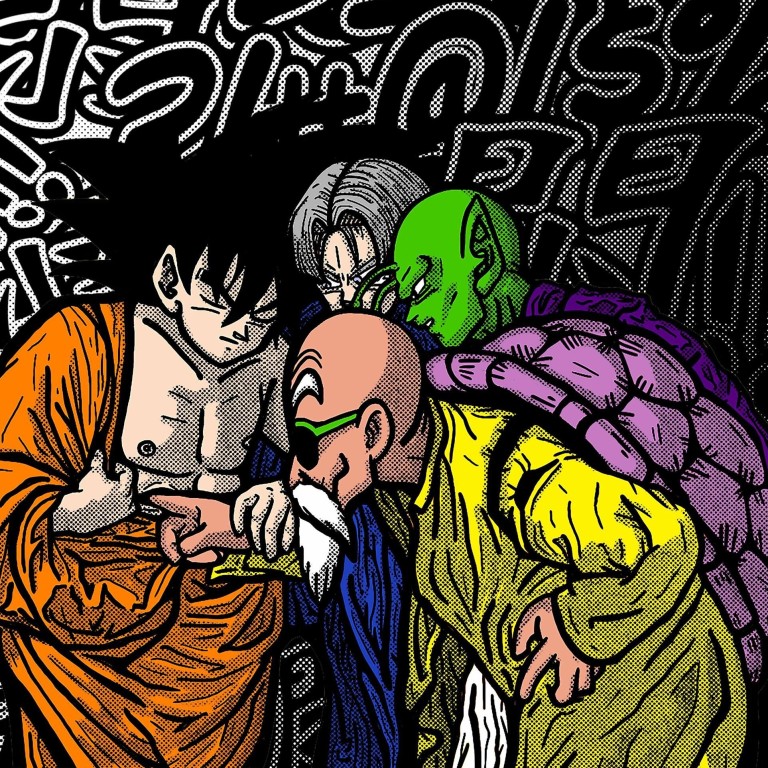

- A Hong Kong artist talks about how it’s ‘a gift and a curse’ and how it affects his art

Artist Ernest Chang says the biggest misconception people have about those who are colour-blind is that they can’t see colour at all.

“The best way to describe it is like seeing the world through an Instagram filter,” says Chang. “The colours are slightly shifted but the general contrasts and dynamics of the light are the same,” he says, adding he was about seven when he discovered he was colour blind.

People who suffer from colour blindness – also called colour vision deficiency – find it difficult to identify and distinguish between certain colours. Chang can see most colours except red and green – a condition known as “red-green” colour vision deficiency and the most common form, affecting around one in 12 men and one in 200 women. The second most common form is blue-yellow.

Despite being a common condition, colour vision deficiency often goes undiagnosed, as patients don’t realise they aren’t seeing colours like other people do.

“The symptoms of colour blindness can vary widely among those affected,” says Nafees Baig, from the Department of Ophthalmology at the Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital.

“People with mild symptoms may not be aware of their problem unless they are specifically tested. Parents or teachers may notice that a child has a problem learning his colours,” she says.

Hong Kong-based Chang says he had trouble reading colour-coded maps in geography class if the cartographer differentiated things with colours. “I still have issues today if these types of charts and diagrams are used,” he says.

As an artist, Chang – who runs The Stallery art studio and gallery in Wan Chai – says colour blindness has been both a gift and a curse.

“People are fascinated that I can still create,” he says. “At times it’s hard to mix colours or see nuances in gradation or hue. It’s also hard to paint realistically or retouch skin tones on photographs.”

Baig says the causes of colour blindness can be congenital and acquired.

“Most people with colour blindness are born with it, a congenital condition,” she says; congenital colour vision defects usually pass from mother to son. About 8 per cent of males and 0.5 per cent of females are affected.

“Most colour vision problems that occur later in life, acquired causes, are a result of ocular disease, trauma, toxic effects from drugs, metabolic disease or vascular disease. Unlike congenital causes, disease-specific colour blindness often affects both eyes differently, and may get worse over time. Acquired colour blindness is often the result of damage to the retina or optic nerve,” Baig says.

The most commonly used test to diagnose colour blindness is the Ishihara colour test, which consists of patterns of multicoloured dots.

People who are not colour-blind can easily make out numbers and shapes among the dots. Those with colour blindness will have difficulty discerning the number or shape in the pattern, or may not be able to find anything in the pattern at all.

British-born Tom Eves, a journalist with the S outh China Morning Post, says he was around five when he discovered he was colour-blind after taking the Ishihara test.

“I was identified as red-green colour blind but in reality it stretches further than that – differentiating between certain shades of red and brown, grey and green, and blue and purple can all be difficult.”

People are fascinated that I can still create. At times it’s hard to mix colours or see nuances in gradation or hue. It’s also hard to paint realistically or retouch skin tones on photographs

Baig says the true inability to perceive any colour at all, and seeing everything only in shades of grey, is a rare form of colour blindness known as achromatopsia, which is often associated with amblyopia (lazy eye), nystagmus (dancing eyes), light sensitivity, and poor vision. It affects one in 30,000 people.

There is an island in the South Pacific, though, called Pingelap, also referred to as “Island of the Colour-blind”, where 10 per cent of the population have the condition.

Baig says there is no treatment for congenital colour blindness, although contact lenses and glasses with filters can help.

“Fortunately, the vision of most colour-blind [people] is normal in all other respects and certain adaptation methods in learning and daily living are all that is required,” she says.

“Computers and other electronic devices often have settings that can be changed to make them easier to use, and there are a number of mobile phone apps available that can help to identify colours.”

According to Hong Kong’s Health Department, people with colour vision deficiency may have difficulties taking up some occupations requiring good colour perception, such as police officer, firefighter, customs officer, prison officer, immigration officer, pilot, pharmacist, laboratory technician and painter.

Eves, 39, says: “I wanted to be a vet when I was young but I found out you couldn’t if you were colour-blind.” He says the rules are less strict today.

The journalist says the question he is always asked when someone learns he is colour-blind is whether he can drive, an activity he has never had trouble with. It has also had little impact on his professional life, though there has been the odd social-life complication.

“I sometimes look at a dark stain on my clothing, or on my dog, and wonder whether it’s dirt or blood, and I frequently pot the brown ball in snooker, thinking it’s a red. And my clothes probably don’t match as well as I think!” he says.