Stress, anxiety, trauma: how Hong Kong Covid-19 travel curbs affect the mental health of expat families, for whom there are few upsides to isolation

- Psychologist’s study of the impact of flight curbs and quarantine on expat families in Hong Kong reveals anxiety, stress – trauma even – and some silver linings

- ‘When will I be able to hold my children?’ one asks. ‘I’m all alone here,’ another says. The impact of long isolation from loved ones has been especially hard

An ambulance pulls up outside one of the austere blocks at Penny’s Bay, Hong Kong’s quarantine camp, where arrivals to the city and close contacts of Covid-19 cases are confined and monitored.

Long-time Hong Kong resident Brooke Babington, still jet-lagged from a flight from the United States, peeks out of the window of the small room she is sharing with her daughter, Bayley. The 11-year-old is huddled on the bed and when she sees the ambulance’s flashing lights she begins sobbing, terrified of being taken to hospital or separated from her mother.

Several weeks on – after 17 days in a quarantine hotel – the pair are now sleeping in their own beds at home in Hong Kong, but Babington says her daughter is traumatised by the experience at Penny’s Bay.

“When the ambulance pulled up in front of our door, we thought they were coming for us. They don’t tell you when they are coming to get you. I liken it to when you hear about people in prison cells not knowing if they are coming to torture you next,” says Babington.

27 hours, 4 suicide attempts: mental health effects of Hong Kong quarantine

The study focuses on expatriates as a unique population because, for the most part, they have come to work in Hong Kong on the premise that they will have home leave and ease of movement – factors which Hong Kong’s stringent travel regulations have taken away.

“With expats, their home country is not Hong Kong, so they don’t have the support network of extended family here. They are missing milestones, 80th birthdays, the birth of children, nieces and nephews. There is a disruption of the extended family that causes a lot of stress and distress,” says Blaine.

Her research, based on in-depth, semi-structured interviews, was conducted in March 2021. Almost a year later, and the situation in Hong Kong has only worsened, she says.

People aren’t scared of the virus, they are scared of being put in Penny’s Bay and separated from their kids

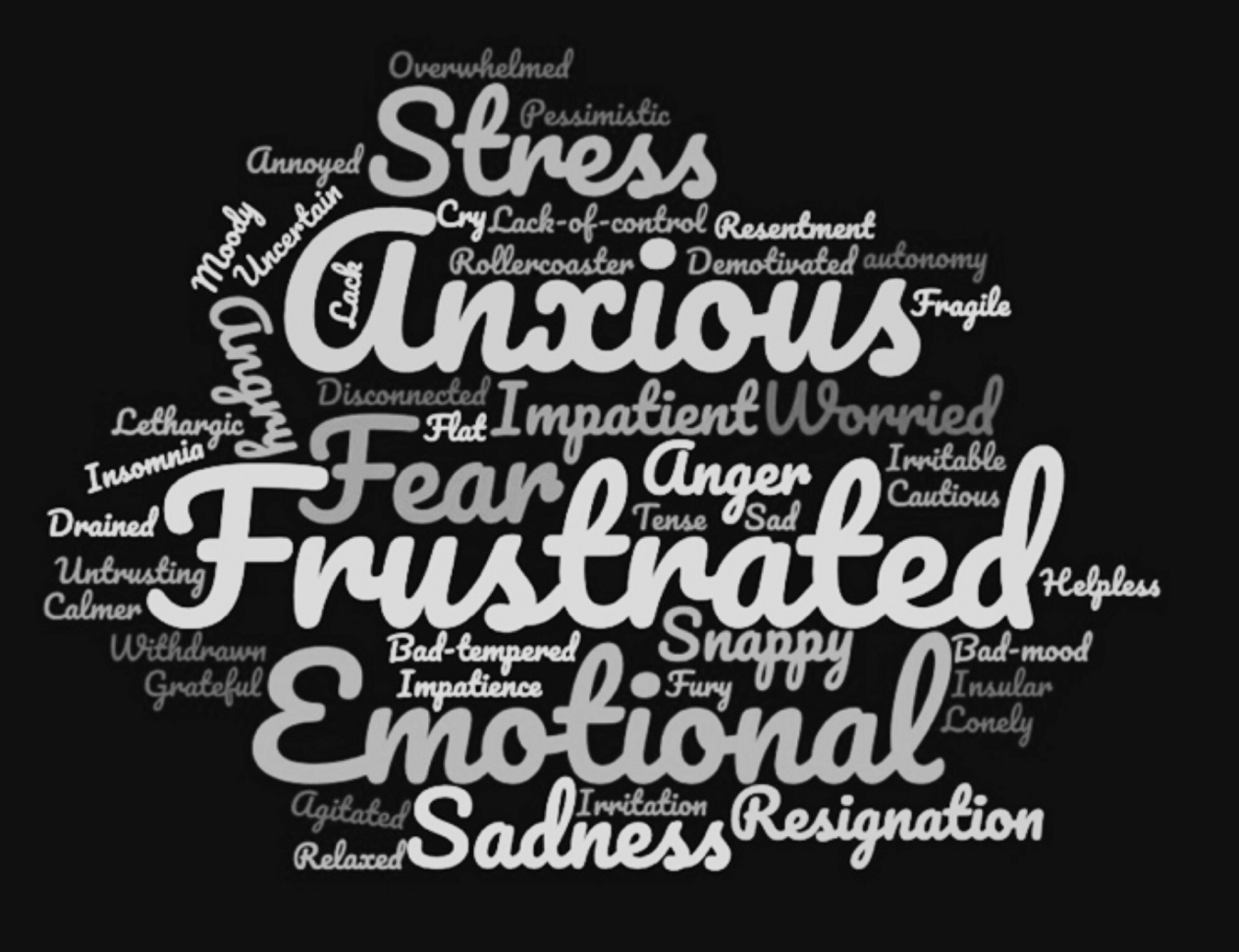

To get an overall understanding of the psychosocial consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, word clouds were generated from the survey responses, with the most frequently used words depicted as bolder and bigger. The word clouds suggested two overarching themes – black clouds and silver linings.

Perhaps the darkest of the black clouds relates to concerns around separation from family. One of the study participants, a young mother, told Blaine: “Not being able to travel or have family come here means I haven’t seen my family since my younger brother passed away last April. I had my first baby in July and none of my family can meet her. I had no family support becoming a new mum.”

A man who has since left Hong Kong said: “My biggest concern is, when am I going to be able to come home? When will I be able to hold my children? When am I going to be able to hug my wife? When am I going to be able to have any sort of sense of connection with family?”

“The restrictions would be easier to stomach if they made sense and the science and reasoning behind what is open and closed, allowed and not allowed, were transparent,” one woman said.

The response from participants was overwhelming when it came to black clouds, but there were some silver linings. Blaine believes it’s important to focus on those “or we’d collapse in a heap”.

Hong Kong’s Covid rules leave families stressed: how to cope – expert tips

Finding new ways to connect and slowing down and gaining time were the brightest of the silver linings. For expats whose job involved extensive travel, the restrictions meant more time at home with their children.

One woman shared how the restrictions meant her husband had connected more closely with their children and another enjoyed the less frantic pace of life.

“I look back on how I used to rush from event to event and it was crazy. I’ve saved so many hours from not needing to plan holidays. I’ve spent more time with my family and on my hobbies due to less commuting and fewer events,” she said.

“Spiritually I feel like we are coming together more as humans in the bigger picture and practically I just feel like there are more important things in life than work and Covid has given me perspective,” one participant said.

Blaine differentiates between resilience – “bouncing back” and post-traumatic growth – “bouncing forward”, where people take stock and think deeply about how to improve aspects of their life.

She expects that the post-traumatic growth that will come in the wake of this pandemic will see people reassess whether the previous model of expat life and travel – “getting on a plane as if it were a bus” – is viable.

“We know that’s not sustainable. In the 1970s, when flights weren’t as frequent, people went home once a year for a month or two. The lifestyle that we had isn’t [sustainable],” says Blaine.

Babington is in Hong Kong for the time being and recovering from her traumatic quarantine experience. “When I was at Penny’s Bay, I talked to the US Embassy and they basically can’t help you, you’re on your own. You don’t have any help. All my family is overseas, so I’m all alone here,” she says.