When death came calling: how the plague swept through Hong Kong

It has been 120 years since the plague darkened our shores, bringing with it a brilliant young scientist who would make a groundbreaking discovery here. Sarah Lazarus looks at its history and the threat posed by a disease that refuses to die

This year marks the 120th anniversary of two events that took place in Hong Kong and had a profound impact on the whole world. One was a human tragedy on a massive scale. The other was a scientific breakthrough of far-reaching importance.

In May 1894, the plague came to Hong Kong. It cut a swathe through the colony, causing widespread suffering and sparking social unrest. From Hong Kong the plague spread far and wide, creating a global pandemic that claimed millions of lives.

In June 1894, young Franco-Swiss scientist Alexandre Yersin came to Hong Kong and made a brilliant discovery. Yersin identified the bacillus that causes plague, laying the groundwork for methods to prevent and cure the disease. The bacillus was later named in his honour: .

These two events are being commemorated at a temporary exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences, on Caine Lane, Mid-Levels, called "Plagues from the Plague to New Emerging Infectious Diseases: A Tribute to Alexandre Yersin & Other Lifesaving Heroes".

The twin anniversaries are a timely reminder that plague exists in today's world. The word "plague" might be redolent of biblical retribution and medieval misery, but the disease itself has not been consigned to history. In fact, since the early 1990s, plague has been making a comeback. Over the past 20 years, more than 50,000 human cases have been reported and the World Health Organisation has classified it as a re-emerging disease.

The world is full of infectious diseases, of varying degrees of nastiness, but plague is exceptional. is the most virulent pathogen ever known and it has killed more people than any other.

says Dr Elisabeth Carniel, head of the Yersinia Research Unit at the Institut Pasteur, the leading French research institute, and director of the WHO's Collaborating Centre of Reference and Research on Yersinia. "A number of teams have conducted genetic studies to pinpoint the origin of the plague bacillus and what we found is amazing. Most bacteria are millions of years old and arose long before human beings. , however, is only 3,000 years old. It's the youngest pathogen we know - in terms of evolution it's like a newborn baby."

Despite the harm it has caused mankind, plague is foremost a disease of rodents. In Hong Kong, the primary host was the brown rat. Other animals, such as cats and camels, can act as intermediaries between the rodent hosts and humans.

The animal hosts are infested with fleas, which act as vectors - they transfer the plague bacillus from one animal to another when they bite. Discerning fleas usually prefer rats but if their options are limited, they will hop onto people and bite them instead, infecting them in the process.

Plague manifests in three forms, depending on the route of infection. The most common form is bubonic plague. When a plague-carrying flea bites a person, the bacteria wash into the wound and travel to lymph nodes in the armpit, groin and neck. The lymph nodes enlarge, forming the "buboes" that give this form of plague its name.

Without treatment the victim experiences seizures, cramps, a hacking cough, acute fever and delirium. The skin blackens as gangrene sets in at the fingers, toes, lips and nose, causing excruciating pain. Death occurs in 40 to 80 per cent of victims within about seven days.

"That's the minor form of the disease," says Carniel.

If the bacteria reach the lungs, the second form - pneumonic plague - develops. Pneumonic plague can be transmitted directly from person to person via coughs and sneezes, so it can spread extremely fast. The mortality rate is 100 per cent and death comes quickly, in one to three days.

From its birthplace in China, the plague bacillus went on the rampage and caused major pandemics on three occasions. The first pandemic, the Justinian plague, swept around the Mediterranean in the sixth century. It killed an estimated 50 per cent of Europe's population before dying out in the seventh century.

The second pandemic started in the mid-14th century and followed the Silk Road, arriving in Europe in 1348, where it became known as the Black Death.

The third pandemic was the one that brought Hong Kong to its knees. It started in Yunnan province in the 1850s and, over several decades, made gradual progress along trade routes until it reached Canton (now Guangzhou) in 1894. With daily water traffic between Canton and Hong Kong, it was inevitable that plague would spread to the colony. The first cases were identified in Tai Ping Shan at the beginning of May.

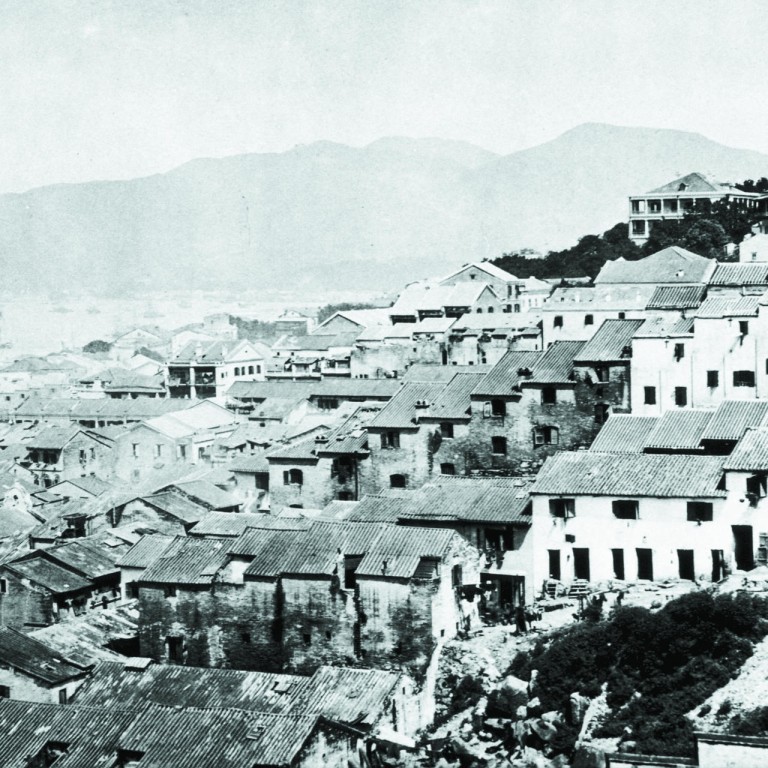

Tai Ping Shan is a small area on Hong Kong Island wedged in between the southern sections of Sheung Wan and Sai Ying Pun. Nowadays it's a maze of ladder streets and alleyways, home to an appealing mix of low-rise residential buildings, quirky shops and funky cafes, alongside traditional printing presses, coffin shops and dai pai dongs. Back in the 1890s, it was a very different scene.

After the British arrived, in the 1840s, they established Tai Ping Shan as a settlement for Chinese workers. As the population grew, the district's tenement houses were sub-divided into tiny, window-less dwellings and large multi-generational families were shoe-horned into them. There was no fresh water supply, no sewerage system and no proper drainage. Contemporary reports describe a hellhole - the inhabitants lived in abject squalor, the streets were mired in filth and the stench was overpowering. It was the kind of place where pathogens thrived and diseases spread like wildfire.

On May 10, Hong Kong was officially declared an infected port. The health authorities sent in teams to conduct house-to-house searches. James Lowson, a Scottish doctor and acting superintendent of the Civil Hospital, described in unsparing prose the full horror of what they found: "On a miserable sodden matting soaked with abominations there were four forms stretched out. One was dead, the tongue black and protruding. The next had the muscular twitchings and semi-comatose condition heralding dissolution … Another sufferer, a female child about ten years old, lay in the accumulated filth of apparently two or three days … The fourth was wildly delirious."

The colonial authorities imposed a strict regime on the local population involving the rapid disposal of corpses, the isolation of infected patients and the disinfection of houses. Later, they forcibly evicted the remaining residents and razed Tai Ping Shan to the ground. Their actions fostered mutual distrust, heightening pre-existing political and racial tensions and amplifying the panic on both sides.

Yersin was dispatched to this chaotic scene by the French government and his employer, the Institut Pasteur, but he wasn't the first scientist to be sent. Three days earlier, celebrated Japanese bacteriologist Shibasaburo Kitasato had arrived from Tokyo. Kitasato had been given a hero's welcome and presented with a well-equipped laboratory in Kennedy Town Hospital. Yersin's reception was chilly by comparison. Kitasato perceived him as a threat. He refused to give Yersin access to patients or cadavers and banned him from the hospital laboratory.

"Because Kitasato was so hostile, Yersin was on his own," says Dr Isabelle Dutry, a former researcher at the Institut Pasteur and co-curator of the "Plagues" exhibition at the Museum of Medical Sciences. "He had only a very basic microscope and a few surgical tools and not much else to work with."

In desperation, Yersin built a simple straw hut near the hospital to use as a laboratory. To obtain samples, he bribed two British soldiers guarding the morgue to turn a blind eye as he removed corpses.

At this point, Kitasato had already declared victory and medical journal had published a report stating that he had discovered the plague bacillus. But Yersin wasn't convinced by his rival's results and continued his own work.

"Kitasato had tested bacteria isolated from a blood sample and Yersin didn't think that was the right approach," says Dutry. "He suspected that the plague bacillus would be found in the buboes. So he opened a patient's bubo, drained the pus and looked at this under the microscope. He later reported to his mother in great excitement, 'I saw a veritable purée of microbes'." Yersin extracted bacteria from the purée, grew a culture and correctly identified the plague bacillus.

In a curious twist, Yersin's lack of equipment was his good fortune. While Kitasato grew his bacteria in an incubator at 37 degrees Celsius, Yersin cultured his samples at room temperature on a bench top in the straw hut. We now know that the plague bacillus grows best at 30 degrees, the mean temperature of June in Hong Kong. At 37 degrees, other bacteria take over and contaminate the sample. In Kitasato's case he had mistakenly identified bacteria responsible for pneumonia, not plague.

Despite his success, Yersin didn't receive the credit he was due within his lifetime.

"Yersin was a shy and introverted man," says Dutry. "He didn't seek publicity or acclaim. But what he achieved was incredible and it's part of his legacy that we [the Institut Pasteur] have branches in Madagascar and many other countries, working at the forefront of plague research."

The plague was still raging in Hong Kong but, despite the risk that it would travel overseas, the British authorities were reluctant to shut down the port.

"Hong Kong was a global transport hub and, by the late 1880s, was being touted as the third largest port in the British Empire," says Dr Robert Peckham, who lectures on the history of medicine and health at the University of Hong Kong. "Given that the whole system was predicated on free trade, the government was cautious about jeopardising the colony's commercial interests. As the gateway for trade with China and the migration of mainland Chinese across the Pacific, Hong Kong was connected to much of the rest of the world. This was the age of steamships and railways - rapid forms of transport that allowed the plague to diffuse globally at a faster speed than ever before."

"Sub-Saharan Africa is currently the most active focus for plague, with over 90 per cent of cases recorded there," says Carniel. "Madagascar has the greatest number of cases, followed by the Democratic Republic of Congo. Plague is gathering momentum in parts of South America and has also reappeared in a number of countries in which it had been silent for decades, including Libya, Algeria and Kyrgyzstan."

Plague is not just a disease of the poor. There are human cases in the US every year, usually when domestic cats come into contact with infected rodents and then return home, infecting their owners.

Rodents carrying the plague live in remote areas across China's Himalayan plateau. Although the plague territory is vast, contact with people is limited and there are only occasional human cases. The last outbreak was in Qinghai province in August 2009. A herdsman caught pneumonic plague from his dog, which had been infected by a marmot - a type of large squirrel. A total of 12 people were infected, of whom three died. The rest were saved by early medical intervention.

"When an outbreak occurs, the important thing is to diagnose the disease and treat it quickly," says Carniel. "Once plague is identified, everyone in the area is treated with antibiotics as a prophylactic measure."

But this safety net can't be taken for granted. "Until the 1990s, we thought that plague was susceptible to all antibiotic drugs," says Carniel. "But with our colleagues from the Institut Pasteur in Madagascar we discovered the first two strains of that are resistant to antibiotics. One was resistant to streptomycin, which is the treatment of choice for plague in Madagascar, and the other was resistant to eight antibiotics, including the three currently recommended by the WHO to treat plague. So that was a shock.

"Fortunately these strains haven't spread into humans but it shows that plague can acquire resistance, and that's frightening."

Plague scientists are also concerned about global warming, which might allow the plague bacillus to expand its geographical range. A research team working in Kazakhstan found that during years with warmer spring temperatures and wetter summers the prevalence of plague in its local host, the great gerbil, was boosted by more than 50 per cent.

The impact of climate change is one of many unknowns.

"There are big gaps in our knowledge," says Carniel. "It's the most pathogenic agent on Earth but we still don't know what makes it so virulent. It seems to become invisible to the host's immune system, but we don't know how. And in some parts of the world we don't know which animals are carrying the plague. This information is critical in trying to control the spread."

Unfortunately, there are impediments to the type of research that's needed. Plague is classified as a Select Agent A - the top category - by the US government, because it's an ideal pathogen for the purposes of bioterrorism.

Plague was the first biological agent to be used as a weapon. In 1346, the Mongol army suffered an outbreak of plague while besieging the Genoese-controlled trading city of Caffa, in modern-day Crimea. Turning a crisis into an opportunity, the soldiers hurled plague-ridden corpses over the city walls. The terrified Italian merchants fled back to Europe by ship, carrying the plague with them.

Plague was later used by Unit 731, a covert research facility run by the Japanese Imperial Army, in Harbin, northeast China, which developed biological and chemical warfare before and during the second world war.

In one of the darkest episodes of the Japanese occupation, Unit 731 conducted lethal experiments on Chinese civilians and conducted field tests by dropping plague bombs on the nation's cities. The bombs had porcelain shells, which cracked open like eggs, spilling a mixture of rice, wheat and plague-infected fleas on the ground. There are no official records of the number of victims but it is known that many thousands were killed.

Research into bioweapons ramped up during the cold war. The potential for harm was much greater by this stage because the plague bacillus could be mass-produced in laboratories and released in aerosol form, spreading pneumonic plague and eliminating the need for fleas.

Plague has not been deployed as a weapon since the 1940s but it remains a significant potential threat. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, a new raft of anti-terrorism legislation concerning research into infectious-disease agents was introduced. Government controls in many countries are now so strong they risk stifling vital research.

"Our work is severely restricted," says Carniel. "It's becoming increasingly difficult to obtain the different strains of , to collaborate with scientists from other countries and to publish academic papers. No one wants to risk plague falling into the wrong hands but the danger is that we might have to stop working on it. And if we do that, and a terrorist releases the bacillus, there will be less scientific knowledge as to how to prevent and control the spread of disease."

Peckham believes that in considering the future, we must look to history.

"Often there appears to be no forewarning of a pandemic, which may move rapidly and give little time to prepare. By analysing past events we can gain insights into how and why diseases have spread. The successes and failures of the past can help us plan for the future and should inform current public-health policy.

"There is so much we can learn from what happened before - we ignore history at our peril."

One thing that all plague experts are certain about is that plague has a future. Reassuringly, Carniel doesn't think we'll see another pandemic on the scale of the past.

"We now know the agent, we know how it is transmitted and we know how to treat it. Even if plague becomes resistant to all antibiotics, we can take action to quarantine it to prevent it being transmitted from person to person."

But she cautions, "It's essential that we keep working. Although the number of human cases is very small when compared to some other diseases, it would be a mistake to overlook the threat it might become. After the first and second pandemics, plague seemed to go away. Both times people assumed it had gone forever. Both times they were wrong. It may remain silent for years but it will always reappear. It's here to stay and I don't think we'll ever get rid of it."