Review | Sin city: book exposes gritty underbelly of 1930s Shanghai

The chancers, adventurers and criminals who made and lost fortunes in China treaty port teetering on the edge of chaos

City of Devils: A Shanghai Noir

by Paul French

Penguin Books

In the uncertain days of Shanghai in the 1930s and early 40s, with Japanese forces getting ever closer and the future of the foreign enclave and its inhabitants in doubt, there was a great deal of money to be made in drink, drugs, gambling and other vices. It was a crazy time for the city and its residents, “like living on the rim of a volcano”, American journalist J.B. Powell wrote.

Based on the true lives of some of the many larger-than-life characters who lived in the city during that era, City of Devils: A Shanghai Noir, by Paul French, brings interwar Shanghai to life in a gritty work of narrative non-fiction.

By the 30s, Shanghai had grown from a walled fishing village into an international treaty port and the world’s fifth largest city, “a deafening babel of tongues, a hodgepodge of administrations, home to hopeful souls from several dozen nations joined together by one simple guiding ethos: money and the getting of it”, French writes.

French’s fascination with this period of Chinese history and the foreigners who were present is apparent in City of Devils, as well as in his back catalogue, which includes books on legendary 30s Shanghai advertising pioneer Carl Crow, the badlands of Beijing and, in Midnight in Peking (2011), the unsolved murder of a young British woman in Beijing in 1937. The latter reached The New York Times’ bestsellers list and is being adapted for television.

“Its International Settlement, French Concession and Badlands district admitted the paperless, the refugee, the fleeing; those who sought adventure far from the Great Depression and poverty; the desperate who sought sanctuary from fascism and communism; those who sought to build criminal empires; and those who wished to forget,” writes French.

Among those who washed up on the city’s shores – and for a brief time made it big – were Joe Farren, a Jewish dancer born in a Vienna ghetto who rose to become a key fixture at some of the swankiest joints in Shanghai, and who eventually had his name above the biggest casino in the Badlands, and “Lucky” Jack Riley, an American prison escapee who became the “Slot King”, controlling every slot machine in town. Both men arrived in the city almost penniless.

The stories of Riley and Farren, however, are the most compelling. After escaping prison in the United States, stealing identity papers from a passed-out drunk and making his way East, Riley wins his first Shanghai bar by cheating its previous owner in a dice game. The establishment is located on Blood Alley, a 100-metre strip of two dozen bars, many without electricity and stinking of sweaty linen, cigarette smoke, cheap working girls and paraffin stoves.

The business gives him a foothold in the Shanghai underworld, and soon he is the owner of a sprawling empire of bars across the city, mostly catering to the lower rungs of society. Drug deals and gambling dens follow, as Riley becomes one of the best-known faces in Shanghai. Meanwhile, Farren rises from being a gifted dancer to running the chorus lines of many of the top venues in the city while also dabbling in the drug trade.

Shanghai in the 30s is a character in itself. “The neon-bright city feeds off its host of 400 million peasants barely surviving in China’s fetid hinterlands and laughs at their degradation,” the author writes. Despite Shanghai serving as a constant reminder of China’s defeat in the opium wars, with its Western consuls, businessmen, soldiers and battleships, they could be key to keeping the threat from Japan at bay.

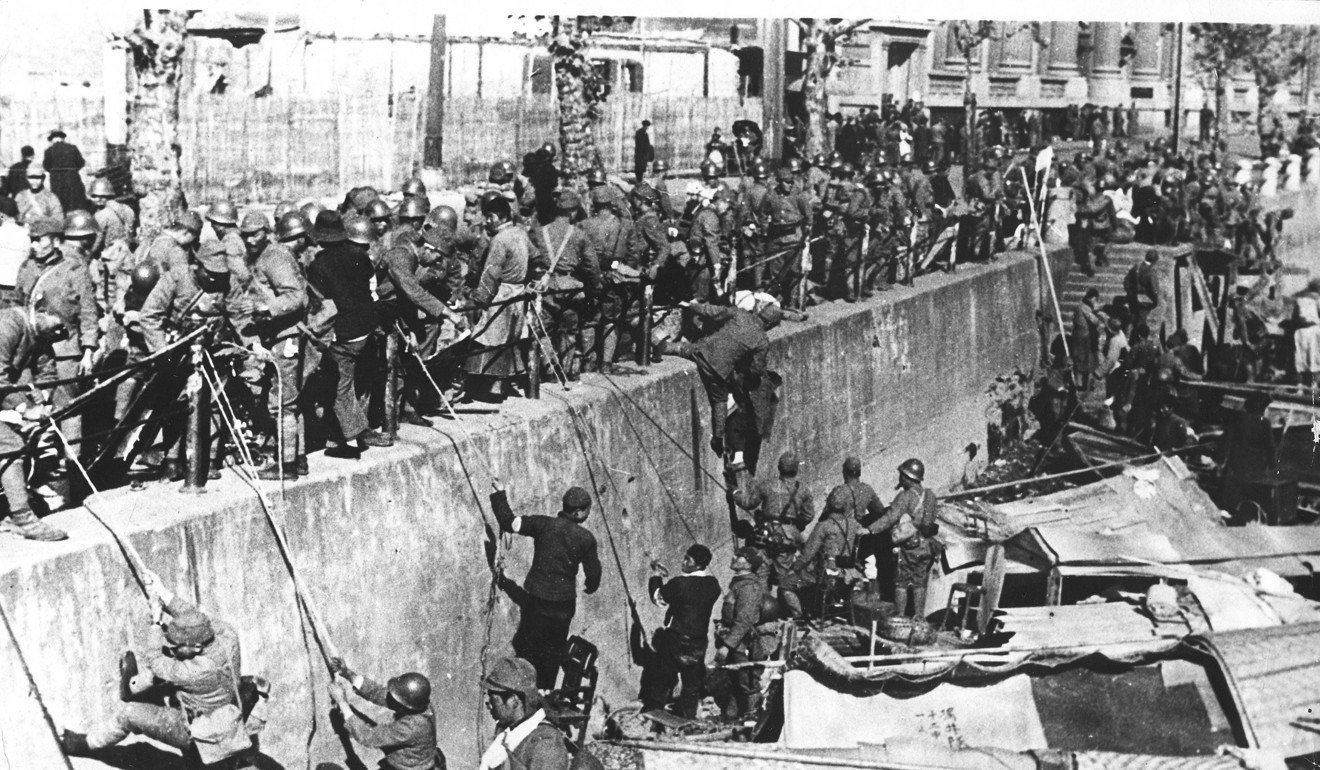

The Japanese eventually attack the Chinese parts of the city, and slowly move to take the rest. Meanwhile, Shanghai’s international occupants continue to gamble and pretend the high life will never end, despite the “stench of the unburied dead wafting over the creek”.

As Chinese and Japanese fighter planes battle in the skies, the foreigners watch the show from the roof of the Cathay Hotel, “white dames in sheer satin and pearls sipping black-market champagne as hell raged overhead and planes spiralled down into the Pootung marshes”.

Inside the foreign enclave, prices rise and many flee, but the Japanese threat means an influx of US and British troop reinforcements, packing the dive bars and gambling joints of the settlement, and lining the pockets of people such as Riley.

However, it’s not all plain sailing in the underworld. While Western authorities try to maintain law and order, Japanese forces put in place Chinese puppets and largely fund their military presence in the city through prostitution, drugs and gambling in the Japanese-controlled Badlands. For those looking to operate illegal gambling joints there, the price is ever-increasing taxation. Assassinations, kidnappings and bloody clashes become regular occurrences.

Among the chaos and death, Farren and Riley work on setting up the largest casino in the Badlands, with room for 600 patrons, and filled with roulette tables, craps, dice and slot machines. Even as the war rages, the venue’s opening is a red-carpet affair, replete with the great and the (not-so-) good of Shanghai, local celebrities and the fawning media.

Farren’s is a place to “forget the war, the barbed-wire barricades, the checkpoints, the shakedowns, the inflation eroding your savings, the newsreels showing Europe going down in flames [and] the bar-stool gossip that maybe that was the last evacuation ship”, French writes.

For a while, despite the war and the Japanese tax, business is good and the partnership endures. Readers know, however, that it won’t last; City of Devils’ opening scene describes Riley, now decidedly down on his luck, robbing the casino he once co-owned at gunpoint.

As with any work of narrative non-fiction, it is unclear how much creative liberty French has taken, but he says he relied heavily on primary and secondary sources. Either way, it is a fascinating tale of a city on the edge, and the men and women who briefly make it big, before it all comes crashing down.