How tourism could change Antarctica, our last wilderness

Human activity on Earth’s frozen continent has never been higher. What effect will a rise in visits by holidaymakers, including Chinese, and scientific researchers have on the polar region? Will the fears of environmentalists be borne out?

IN ANTARCTICA IN February, there is barely any night. At 10.30pm, as the MS Fram nudges its way through the Lemaire Channel, every passenger aboard is on deck to watch the sun’s blood-red orb hover above the horizon. Hemmed in by steep cliffs, the waterway’s unruffled surface is mirror-like, reflecting snow-clad peaks and fractured glaciers with startling clarity.

Lying off the west coast of Graham Land, the 11km Lemaire Channel is just one highlight of a voyage through the Antarctic. Carrying cargoes of people, ships such as this – a specially designed 400-passenger polar cruise vessel operated by Norwegian company Hurtigruten – are increasingly making journeys to the end of the world.

This is the Earth’s last great wilderness. It is here that humans have a chance to show that we can manage the environment responsibly

There is nowhere else like Antarctica. It is the driest, coldest, windiest place on the planet. Drawn to its spectacular scenery and long list of iconic species, more and more tourists are choosing to visit this harsh yet pristine wilderness. It is a place where humans are almost never in control and yet, as man’s activities here intensify, nature’s rule over the frozen continent is increasingly fragile.

According to the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO), the total number of visitors travelling to the continent with its members during the 2015-16 season was 38,478, up nearly 5 per cent year-on-year. This will rise to an estimated 44,000 next season (although about 10,000 will not actually set foot on Antarctica).

“We think this is sustainable, with some room for further growth,” says Amanda Lynnes, IAATO communications and environmental officer.

A visitor to Antarctica can expect a somewhat unconventional tourist experience. On land there are no bathroom facilities, food and drink is strictly prohibited and shore time and group numbers are tightly controlled. As those visiting the continent typically appreciate the lack of crowds and man-made infrastructure, these limitations are rarely a problem.

But even operating within these restrictions, most tourist landings in Antarctica are, by their very nature, high impact. People on expensive packages want to see and get close to penguins, seals and whales. Wildlife-rich, easily accessible sites in Antarctica are relatively scarce, concentrating tourists in a few areas. Worries about the negative impact of increased traffic, both on the tourist experience and the local environment, have given rise to calls for a cap on visitor numbers.

“If there was overcrowding in Antarctica, we would have to raise our hands and advocate efforts to reduce the impact,” says Hurtigruten chief executive Daniel Skjeldam. “But at the moment, we feel that those who have witnessed Antarctica are its greatest defenders and ambassadors.”

Others are concerned about how new operators will fit into a tightly regulated tourist model that currently seems to work.

“If they don’t conform to the model then it will be difficult to control the industry without more binding regulations,” says Claire Christian, acting executive director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, a global group that works to ensure environmental issues are prioritised through the Antarctic Treaty System.

As the sun rises over a calm Errera Channel, a trio of gentoo penguins glide through the crimson water, en route to offshore feeding grounds. Below the port bow of the Fram, a crabeater seal basks lazily on a pancake-shaped floe. For those on deck, it’s another magical Antarctic experience.

Lying off the west coast of Graham Land on the Antarctic Peninsula, the Errera Channel is a narrow, dog-legged waterway that runs for 9km between Rongé Island and the Arctowski Peninsula. More complex than its better known cousin, the Lemaire, it boasts more places to visit and a broader range of wildlife. The Fram launches a flotilla of smaller boats, as passengers go ashore to spot whales from land.

I know the water is going to be absolutely freezing. But how many times in your life do you get to go for a swim in the Antarctic?

While the vast majority of tourists are still shipborne, traditional expedition cruises, involving small to medium-sized ships (such as the Fram), rubber boat landings and education programmes, are increasingly complemented by larger cruise liners (which do not make land), overflights, fly-sail operations and land-based tourism. Today’s visitors can choose a wide range of adventurous pursuits, from kayaking, overnight camping and helicopter excursions right through to scuba diving, cross-country skiing and mountain climbing.

“We need to comprehensively assess the potential impacts of these activities,” says Christian. “Even though they are supposedly vetted by national authorities, it’s difficult to assess overall or cumulative impacts on a case-by-case basis.”

On board the Fram, where pampered passengers are offered activities such as hiking and camping, not to mention daily landings at numerous Antarctic Peninsula sites, the level of environmental awareness is high. They are instructed to vacuum their clothing to prevent transfer of invasive species and are strictly forbidden from bringing anything – organic or otherwise – back from landings. Boots and waterproof suits are rigorously sterilised.

“We inform guests about the vulnerability of Antarctica and host prominent environmentalists as onboard lecturers,” says Skjeldam. “We minimise fuel consumption and follow strict guidelines with regard to wildlife encounters. We even carry state-of-the-art oil booms that can be deployed rapidly to contain leaks.”

The ongoing effects of climate change, particularly on the relatively biodiverse and climate-sensitive Antarctic Peninsula, make it difficult to assess the negative effects of tourism.

“Over the past 50 years, there has been virtually no discernible impact on the Antarctic environment by tourism,” says Lynnes. “Continued monitoring is vital, however, and IAATO continues to work with Antarctic Treaty parties to improve it.”

The environmental monitoring of scientific activity in Antarctica could also be better. Antarctic Treaty signatory nations are required to supply details of their monitoring work through an Antarctic Treaty System database. To date, only a handful have done so.

“We still don’t have good data on whether and how activities such as tourism or scientific research are impacting biodiversity,” says Christian. “We do know that pollution from scientific stations has occurred and is detectable in the environment.”

Kevin Hughes, environmental research and monitoring manager at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), says: “Until all Antarctic Treaty nations engage with their monitoring obligations and develop a coordinated, continent-wide view of human impacts, the environment of Antarctica will remain under threat.”

Coming to the end of her two-week Antarctic cruise, the Fram arrives at Deception Island, in the South Shetland archipelago. With the boat moored safely in Whalers Bay, protected by the rocky ramparts of the island’s volcanic caldera, a contingent of Chinese passengers prepares to go ashore. A shipboard announcement in Putonghua – used in addition to English and German – calls them below, to the boat deck.

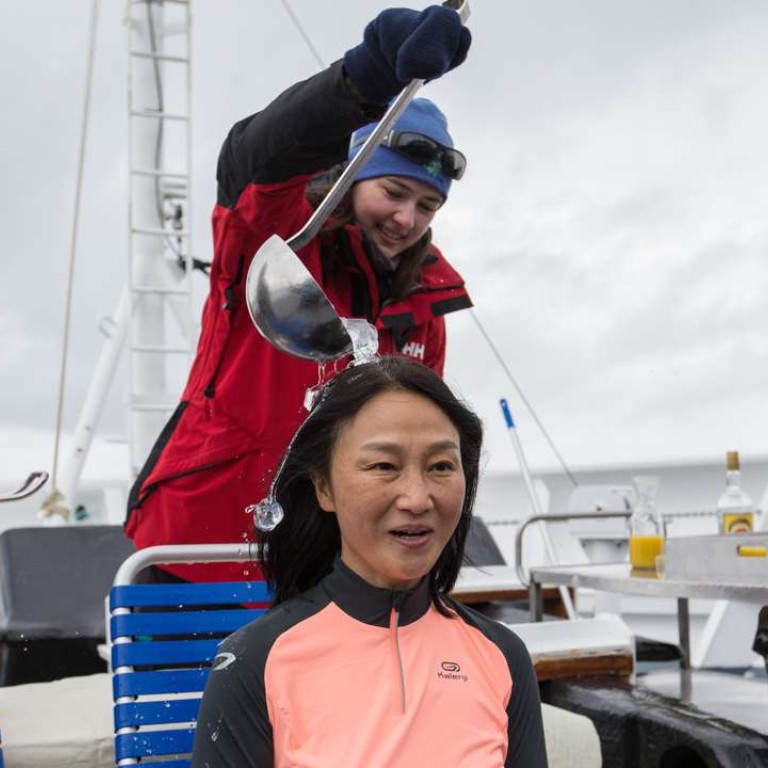

Beijinger Cindy Li is taking part in a 10km hike to Baily Head, to see a huge colony of chinstrap penguins. She is deciding whether to follow this up with a swim in the bay, which, despite being gently warmed by volcanic activity, remains frigid.

“I know the water is going to be absolutely freezing,” she says, with a smile. “But how many times in your life do you get to go for a swim in the Antarctic?”

The number of Chinese tourists visiting the Antarctic each year is exceeded only by those from the United States and Australia. According to IAATO statistics, more than 3,500 Chinese visited Antarctica in 2015-16, compared with fewer than 100 in 2005-06. Chinese tour organisations are increasingly targeting wealthy travellers seeking an “extreme” getaway.

The frankly racist ‘yellow peril’ fears of Chinese tourism swamping the Antarctic are not borne out by the statistics

Some are now worried about what effect this Chinese tourist boom may have on Antarctic biodiversity, with widespread media reports of “disturbed” penguins. Yet many believe such fears are exaggerated. Given the massive Chinese market, and the country’s expanding middle class, the Chinese contribution to Antarctic tourist numbers remains remarkably small.

“The frankly racist ‘yellow peril’ fears of Chinese tourism swamping the Antarctic are not borne out by the statistics,” says Australian polar specialist Dr Alan Hemmings. “They seem particularly absurd when one hears this in Australia, with its greater numerical contribution from a relatively tiny national population.”

As the number of Chinese polar-tourism vessels increases, so the upward trend in the number of Chinese visiting Antarctica will surely continue. It will be interesting to see whether Chinese tour companies elect to join IAATO.

“A major challenge for IAATO is to demonstrate its usefulness to Chinese and other non-Western Antarctic tourism operators,” says Hemmings.

At Station Y, a former British research base just off the west coast of Graham Land, it’s not only the snow and ice outside that’s frozen. For the tourists walking through the collection of rudimentary wooden buildings, it’s as though time stopped in 1960. Heavy oilskin jackets and trousers hang in a hallway while pairs of regulation army plimsolls stand neatly by every bunk. But it’s the station kitchen which provides the most fascinating insight into a bygone polar era.

The shelves are a testament to British post-war cuisine, filled with such staples as powdered mashed potato and custard, tinned cheese and meat bars. And, of course, jar upon jar of Marmite.

Faced with some of the most inhospitable conditions on the planet, man’s presence in the Antarctic hasn’t always been a tale of glamour and heroism. On a rocky promontory overlooking Station Y, a simple monument commemorates the lives of three scientists who, in 1958, disappeared while on a sledging expedition across nearby sea ice. Although some of their dogs returned, the men were never seen again.

Over the past century, Antarctica has been home to myriad fishing villages, whaling stations, scientific bases and way stations for exploration. The Antarctic Treaty states that any country wishing to discontinue its presence in Antarctica must pack up completely and restore the land but many choose instead to keep their bases open with a skeleton staff. This is often by far the cheaper option.

Other countries have chosen to preserve old Antarctic bases as museums. Station Y, which was opened by the British in 1955 and closed five years later, is maintained by the United Kingdom Antarctic Heritage Trust, a charity that works to restore and maintain a range of abandoned British Antarctic buildings across the continent.

AT THE ROTHERA Research Station, on Adelaide Island, to the west of the Antarctic Peninsula, a group of passengers from the Fram gather round a giant indoor aquarium. Below the gently bubbling water, a smattering of giant sea spiders and marine woodlice patrol the sandy floor. Thriving only

in near-freezing conditions, these supersized creatures are highly vulnerable to global warming.

Rothera is Britain’s largest working research station in Antarctica. It is run by the BAS, which undertakes research into everything from evolutionary biology to climate change. In the 1980s, it was the BAS that discovered the hole in the Earth’s ozone layer.

Since the influx of national scientific research programmes that began with the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958), an increasing number of permanent and semi-permanent research facilities have been constructed in Antarctica. Representing 30 countries, more than 120 stations have been built (about 70 are currently operational), with most located on the continent’s ice-free coastal fringes, to facilitate easy access.

For countries active on the Antarctic continent, these stations typically fulfil two objectives: they demonstrate a commitment to scientific research (a prerequisite for attaining consultative status at the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting); and they support geopolitical aspirations.

As many countries face stagnant Antarctic research budgets, others are playing catch up. The maiden voyage of the Chinese ice-breaker Haibing 722 in January signalled the country’s steadily growing presence and capabilities in and around the Antarctic continent. Indeed, in Australia last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping vowed to continue developing his country’s polar prowess.

Although Beijing did not establish its first Antarctic research base until 1985, Chinese operations on the continent are already the fastest growing of the 53 signatories to the Antarctic Treaty. The country opened its fourth research station last year, chose a site for a fifth and is currently investing in ice-capable ships, planes and helicopters.

But China isn’t the only country growing its presence here. Using existing Soviet bases, Russia is expanding its development of a global positioning system meant as a rival to the American GPS. The country is also investing in a new Antarctic runway and ice-capable planes and vessels, while this year saw the first Russian naval expedition to Antarctica in three decades.

Many analysts believe recent Russian and Chinese activity in the Antarctic is closely tied to future exploitation of the continent’s resources. A range of minerals has been identified on or around the continent, including deposits of coal, iron, copper, gold, silver, uranium and titanium. Rough estimates place total Antarctic oil reserves between 50 billion and 203 billion barrels (more than those of Kuwait or Abu Dhabi) while natural gas reserves are projected at 106 trillion cubic feet.

Under the terms of the Madrid Protocol of the Antarctic Treaty, the ongoing prohibition on mineral resource activities in the Antarctic is open ended, but could be challenged sometime after 2048. How likely this is remains to be seen.

“Calling for a review would open the proverbial can of worms,” says Hemmings. “It is debatable whether the majority of states would wish to expose themselves to the risks involved.”

The scale and geographic scope of human activity in the Antarctic is growing inexorably. An increase in infrastructure development and the number of people involved as scientists, tourists, guides and logistical personnel is undoubtedly leading to growing pressure on continental ecology.

Ways of managing the impact of such activity, which should include greater monitoring, will only be successful if they conform to a unifying, strategic vision. Such a vision is precisely what the annual Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) is supposed to deliver.

In recent years, however, the ATCM has been shortened from 10 to eight days, and participating parties have found it increasingly difficult to agree on legally binding measures.

“The evidence is that Antarctic Treaty consultative parties as a whole are not substantially engaged in utilising the tools they have, let alone developing a strategic vision,” says Hemmings.

“How the growth and diversification of Antarctic tourism will be monitored and managed going forward is a key question that needs to be urgently addressed,” says Christian. “Antarctic Treaty members must take more of a proactive approach to agreeing a comprehensive, continent-wide, long-term vision.”

Countries with an Antarctic presence, meanwhile, should be judged on their behaviour, rather than the level of investment in their national programmes. It is disingenuous for Western countries – who have themselves carved up Antarctica with spurious territorial claims – to highlight the importance of their own Antarctic research, only to look askance at such activity when China or India do the same.

Paradoxically, both science and tourism have the potential to damage the very qualities that draw scientists and tourists to Antarctica.

“Most of those who have seen Antarctica understand how vital it is to protect such a unique place,” says Rune Andreassen, captain of the MS Fram. “This is the Earth’s last great wilderness. It is here that humans have a chance to show that we can manage the environment responsibly.”