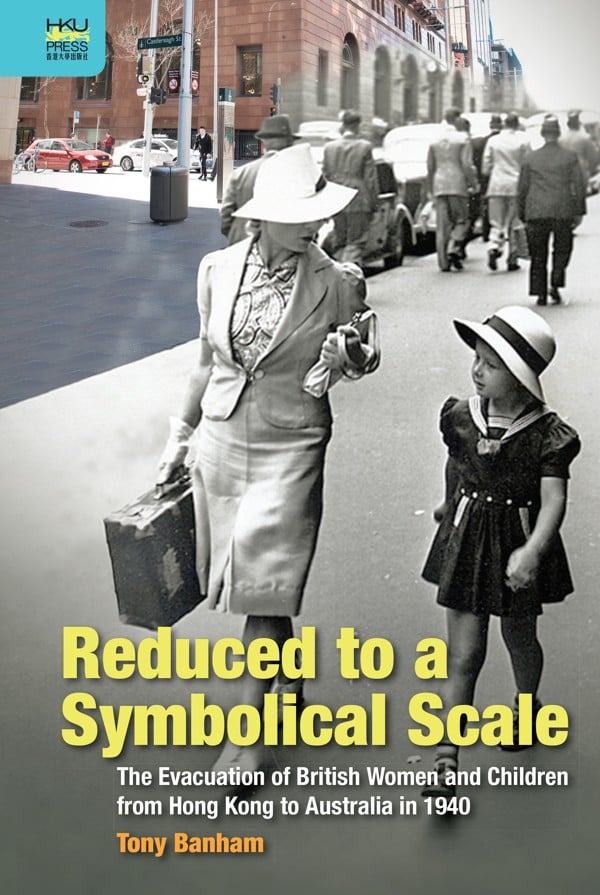

How British in wartime Hong Kong evacuated women and children – an excerpt from new book by historian Tony Banham

Banham’s book Reduced to a Symbolical Scale reveals how families were split during the war, with the men and their adult sons left behind in Hong Kong after the women and children were evacuated

In July 1940, as the threat of Japanese invasion intensified, the largest evacuation in Hong Kong history got under way. More than 3,000 British women and children had to say goodbye to husbands and fathers, and, in some cases, sons and fathers, before being shipped to Australia, via Manila.

It is an operation examined in Reduced to a Symbolical Scale: The Evacuation of British Women and Children from Hong Kong to Australia in 1940 (Hong Kong University Press), the latest book by historian Tony Banham, founder of the Hong Kong War Diary project.

The following is an excerpt:

While in general it was the father and husband who had been left behind in Hong Kong and was now a prisoner, families with older siblings had also been split. In at least one case, an evacuee had come of age in Australia and elected to return to Hong Kong and sign up: John Ken FitzHenry (who had been evacuated to Australia aged sixteen but returned when seventeen and joined the HKVDC – Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps) became, as a gunner at the surrender of Hong Kong, one of the youngest POWs.

More commonly the older siblings had simply been left behind when the women and younger children left for the Philippines. Mary Lapsley had evacuated with children Mary, Cecilia and Harold, leaving her husband Robert and three older sons (Robert, Tony and Ferdinand) behind. As members of the HKVDC, all four of these men had become prisoners. Georgina Foster had evacuated with two daughters and two younger sons, leaving her husband and oldest son (both serving in the Royal Scots) in the garrison. Her husband would survive the surrender, but the Japanese took young Jack out of St Albert’s Hospital when they captured it on December 23, 1941 and he would never be seen again.

Neve’s son describes the day that he was on his way to play a game of junior inter house rugby at the school playing fields in Rose Bay (Sydney), when another boy came running up and told him to report to the headmaster’s office: “I protested that I was about to play rugger for my house but he insisted that it was so important I had to go immediately [...] I had no inkling of why I was wanted and spent the whole of the walk back wondering what misdeed could possibly warrant such an urgent summons. I knocked timidly on the door of Mr Hone’s study. It was immediately opened by Miss Fallon the matron in her white uniform and forbidding horn rimmed spectacles. She was a capable person who stood no nonsense from us boys but could show sympathy when needed. This was odd; what was up? The headmaster anxiously told me to sit down on the sofa in front of his desk. Miss Fallon sat beside me. I do not remember his exact words but he then told me in a straightforward and sympathetic manner he had just heard from my mother that my father had died of his wounds. Although he had done it at least half a dozen times before, it was clear to me he found it difficult and upsetting to be the bearer of such sad news.”

Initially the captured men were spread all over Hong Kong, but by the end of January 1942 they had been concentrated – except for those still in hospital – at a refugee camp in North Point, and the pre-war Sham Shui Po barracks. In April 1942 the majority of officers were moved to a separate camp on Argyle Street, and the North Point POWs moved to Sham Shui Po. There the situation stabilised until September. Slowly, and over a matter of months or even years the evacuees would discover where their husbands and fathers were. Ron Brooks, son of Master Gunner Charles Brooks, Royal Artillery, who had survived the fighting: “In July 1942 my mother had official notification that my father was a prisoner of war. Via the Red Cross she also had at least two letters from my father from the POW camp in Hong Kong.”

Altogether, some 500 of Hong Kong’s prisoners of war (the majority being HKVDC or HKRNVR – Hong Kong Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve – the remainder senior regulars) had had their families evacuated. Many of these men would later be drafted to camps in Japan, or die on the voyage.

But the “enemy alien” civilians remaining in Hong Kong had a different experience. Immediately after the Christmas Day surrender, they found themselves in a dangerous vacuum. Law and order – not to mention electricity and water – had at least partially broken down, and food was hard to come by. But ten days later they were ordered to register with the Japanese authorities and were temporarily billeted in cheap hotels along the Sai Ying Poon waterfront. Towards the end of January 1942 they were rounded up and transported to a Civilian Internment Camp in Stanley on Hong Kong Island’s south coast, a site that had been selected by the director of medical services, Percy Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke. Consisting of the buildings of St Stephen’s College on the west side and the living accommodation for the warders at Stanley Prison on the east, the camp housed civilian men, unevacuated women, and children. In total, at its maximum, it held some 3,325 non-combatants of all nationalities. Nine hundred and nine of the British internees were women, whose most common profession was “housewife”, and a further 284 were children. While some of the women had clearly held essential roles and a handful of others had arrived in Hong Kong after the evacuation was called off, a large percentage could have been evacuated. There were also a fair number of internees – almost sixty – who had evacuated and returned, voluntarily or otherwise.

Marina, whose father had been a prison warder at Stanley, had been evacuated. Her possessions, like everything left behind in the area now bounded by the camp, were used for cooking fires or whatever other purposes the internees required. It was far from being the worst internment camp in the Far East, but it was a very different environment from the pre-war world of plenty that the majority of internees had known. While their privations were of course far worse than anything experienced in Australia, and there was the ever-present threat of violence from the guards, there were very few decisions to be made. In that one respect their lives were at least simpler than those of the evacuees.

Included in Stanley’s internees were more than two hundred men whose wives and children had been evacuated. Lionel Lammert, whose wife Florence, and daughter Marjory (aged 20 then) had evacuated in 1940, was typical of these men. His 24-year-old son (also Lionel) had stayed in Hong Kong. Policeman Wright-Nooth noted as he walked around the Internment Camp: “I met old Lammert on my stroll today. He tells me he hopes his son is still alive. As far as I know from authentic sources he has been beheaded.”

The younger Lammert had indeed been decapitated after capture in Causeway Bay, for refusing to salute a Japanese soldier; even within the colony, let alone in Australia, there was still uncertainty about who had survived.